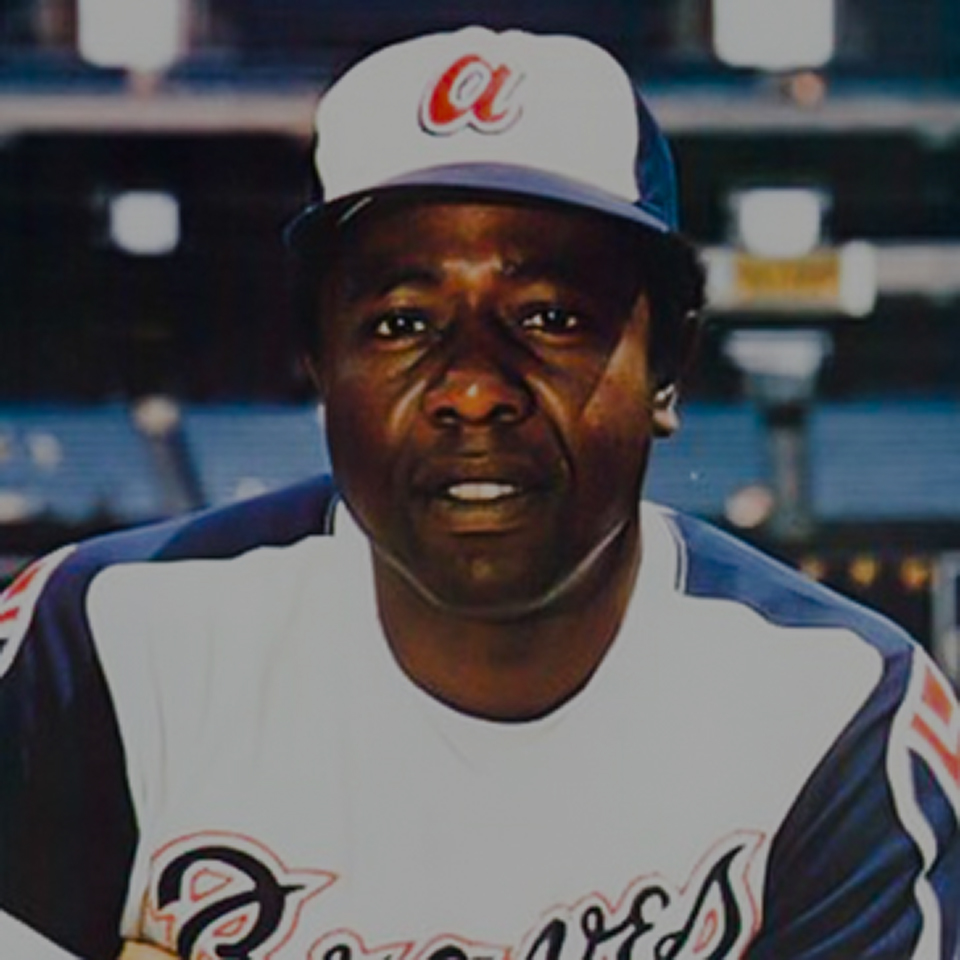

On January 22, baseball great Henry Aaron died in his sleep at age 86. A son of Mobile, Alabama, Aaron grew up in poverty amid the worst abuses of the segregated south, only to become the baseball player who smashed the hallowed home-run record of Babe Ruth.

That is the single act for which Hank Aaron is best known and justly celebrated, but he was more than that. He was a gentleman, an activist, and (most surprisingly for some) he was a Catholic too.

He was the antithesis of the man whose record he broke. Whereas Ruth was larger-than-life, often brusque, vulgar, and self-aggrandizing, Aaron was something of a stoic, letting his feats on the baseball diamond speak for themselves and help to break down racial barriers. He had endured death threats in pursuit of the record, but kept on, and in the famous call of Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run on April 8, 1974, against the Dodgers, announcer Vin Scully drew out the deep significance of the event: “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta, and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep south for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol.”

Led by Jackie Robinson, black men had only been playing Major League baseball for ten years when Aaron won his only National League Most Valuable Player Award, along with his only World Series championship in 1957. By the time Aaron was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1982, along with fellow African American superstar Frank Robinson, there had only been five other black members honored for their work in the Major Leagues (Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Roberto Clemente, Ernie Banks, and Willie Mays, with several other previous inductees from the Negro Leagues). “We changed the face of baseball,” Aaron acknowledged.

In 1959, two years after winning the MVP, Aaron and his wife and children were baptized and received into St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, under the instruction of Fr. Michael Sablica, a priest who was vocal in his support of the civil rights movement and believed the Catholic Church could be a powerful tool for social justice. Hank Aaron described him as “more than just a religious friend of mine, he was a friend because he talked as if he was not a priest, sometimes. . . . He was just good people.”

Throughout his career, Aaron was known to keep a copy of Thomas à Kempis’ devotional classic The Imitation of Christ in his locker.

Aaron and his wife, Barbara, divorced in 1971, and Aaron wed his second wife, Billye, in 1973. It is not clear what Aaron’s status with the Church was at the end of his life. His funeral on January 27 was held not in a Catholic cathedral but at Friendship Baptist Church in Atlanta.

Maybe one day we will know more of the story of Aaron’s faith journey. Perhaps his distancing himself from the Church is as simple as the all-too-common tale of rethinking the Church’s claims in light of a failed marriage.

Or maybe he and his first wife were captivated by the Church at her best—“Here comes everybody”—at a time when few Protestant denominations aspired to diversity and universality.

Or maybe that allure of truth, beauty, and goodness wore off at a time when there were very few black priests in America, and even fewer black bishops.

Or, to the shame of the Church, perhaps Aaron disliked finding common racism where it had no business being. In the 1972 biography Bad Henry, the authors tell of Fr. Sablica reminding Aaron to attend Mass while at spring training in Florida, and Hank Aaron looking straight into the priest’s eyes, declaring, “Down there, they won’t let me go to Mass.”

Aaron said in his Hall of Fame induction speech, “The way to fame is like the way to heaven. Through much tribulation.”

Aaron’s quest for justice for his fellow black men and women was steady, not flashy, and so was his faith. In the offseason of 1973-1974, for example, Aaron received racist hate mail and death threats as it became apparent that he would break Babe Ruth’s record shortly after the new season began. And when he finally hit number 715, two white college students rushed the field while he was rounding second base. For a moment, it looked like he might be under attack; but it turned out they were just excited fans cheering him on.

For a whole lot of reasons, Vin Scully picked just the right word to describe Hank Aaron when the triumphant slugger finally touched home plate: “Relieved.”

The image evokes St. Paul: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race,” and we hope, perhaps, “I have kept the faith” (2 Tim. 4:7).

Rest in peace, Hammerin’ Hank.