Writer Heather King’s life has always been an open book, but one chapter needed exploration. Kerry Trotter spoke to King recently about her new work “Poor Baby: A Child of the ’60s Looks Back on Abortion” and the harrowing journey it recalls.

“I was both the person who had aborted my children and the lover of Christ; both deeply selfish and deeply giving, both the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene— and something more besides. I would continue to stumble, to be broken and weak, to fail. But I could also live out the rest of my life in a way befitting the mother my children deserved; the mother I would liked to have been but had not been able to be; the mother who, from a supernatural standpoint, I actually was.” -Heather King, “Poor Baby”

At a time where so much of what is religious has become almost inextricably tied with the political, where social issues hinge more on legislation than any alteration in one’s moral code, when differing beliefs can sever relationships, Author Heather King tackles a most heated topic but manages to step clear away from the fray, and somehow, emerge with a clear message

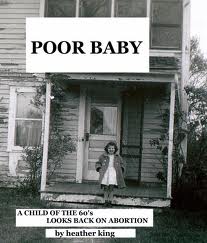

In her newest work, “Poor Baby: A Child of the ’60s Looks Back on Abortion,” a self-reflective journey hovering somewhere between essay and autobiography, King tells the story of her three abortions and the decades of pain, anxiety and, ultimately, forgiveness that followed.

And also a revelation surprising to her: that she could be a mother to her lost children.

“I had suffered in silence as so many women do,” King, 59, said recently in a telephone interview. “It’s a story about death and resurrection. It’s a story about Christ.”

Suffering, she writes, is the “most radical, most incendiary, most taboo subject” in which we can engage, and nothing can alienate a person more than suggesting that our relationship to suffering can illuminate the meaning of life. Suffering is, for so many, born of sin but then reconciled through God, and King’s experience with it is no different. Her desire to grasp the truth meant getting right back into the muck, the mire of it all and coming out the other end.

And in the end, she was still a mother.

“Poor Baby,” King said, isn’t taking a political side on the abortion issue, but just telling it like it is—for her and, in many respects, for the millions of other women who’ve had abortions but aren’t able to talk about it due to shame, stigma, and the breach in understanding just how much grief surrounds the decision—and lingers well after. Scare tactics and feel-good stories of women who “chose life” don’t always quite get at it, she said, neither does the knee-jerk rationale for its benefits. The implications are so much bigger.

Through counseling King was invited to pursue a relationship with the children she

lost, give them names, personalities, neuroses (“One is still pissed off at me,” she quipped), and a place in the universe.

“With this subject, you could not articulate the depth of this sorrow,” she said. “It’s when you get way, way down that you are in the garden of Gethsemene with Christ.”

King is, as she’s always been, candid about her life—her struggles in childhood, her battle with alcoholism, failed relationships, and her abortions. But there’s a redemptive element in her writing, too—her sobriety, her conversion to Catholicism, her writing career, her life full of friends, books and good food, her path to forgiveness. The conversion is of particular note, in that her faith has filled the craters, helped heal the wounds, facilitated the catharsis, introduced her to her children.

“We have this God that is so magnificent, so paradoxical,” she said, “to kill your own kid and God could, even out of that, bring new life.”

The frankness of language and the courageously honest baring of her deepest wounds are what separates King from the pack of writers to tackle the topic—a pack that is surprisingly thin given the pervasiveness of the issue in the political sphere. But it’s also fear that has kept women who have had abortions largely mute, and the reluctance to have one’s name associated with such a divisive and uncomfortably issue.

“It’s the death of the soul,” she said. “There’s so much shame around it, which is great proof that it’s wrong.”

But King is quick to point out that this is not a manifesto for political gain, and that it’s not meant to influence legislation one way or another. It’s a “human situation,” she said. But more specifically, it’s her situation.

“I just wanted to tell my story,” she said. “I can only speak for myself.”

What she speaks of is painfully sad, terrifyingly truthful and, at times, funny. The tone, King said, was difficult to strike, but she was more concerned about writing her story well than pleasing any particular demographic.

“I’ve laid myself out there in my writing,” she said. “Nobody could be more violent to me than I’ve been to myself.”

King recounts the story of the photograph of her as a child that triggered this explorative journey (the book’s cover photo), the life decisions she had made based on fear, the wonderful women and men (and faith) who guided her toward healing, and the relationship she shares today with the three children she lost many years ago. It was a relationship she had for so long believed she hadn’t earned, but facilitated by her faith in Christ, was able to embrace. Her evolution of self, her strides to pursue knowing her children, and her writing it all down was finally making her the mother her kids deserved, King said.

As part of her counseling, she writes, King made a collage of and for her children—the first tangible

time King indulged in thinking of them as real kids, her kids. The collage now hangs in a lofted portion of her home.

“I love that they are above me,” she said.

It’s the paradox of life, she said, that leaves her in wonder: how one can be both the Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary yet still have a place at God’s table. The complexity of our relationship with God, our relationship to suffering, and our love for the children from whom we willfully part is not something that can be easily parsed into one of two political camps. Moreover, a mother’s love is not so easy to shake.

“It’s a long, painful journey,” she said. “But we really get to be reborn so we don’t have to be weighed down in bondage.”

To read “Poor Baby” on your computer or e-reader, click here.

To read Heather King’s “Shirt of Flame” blog, click here.