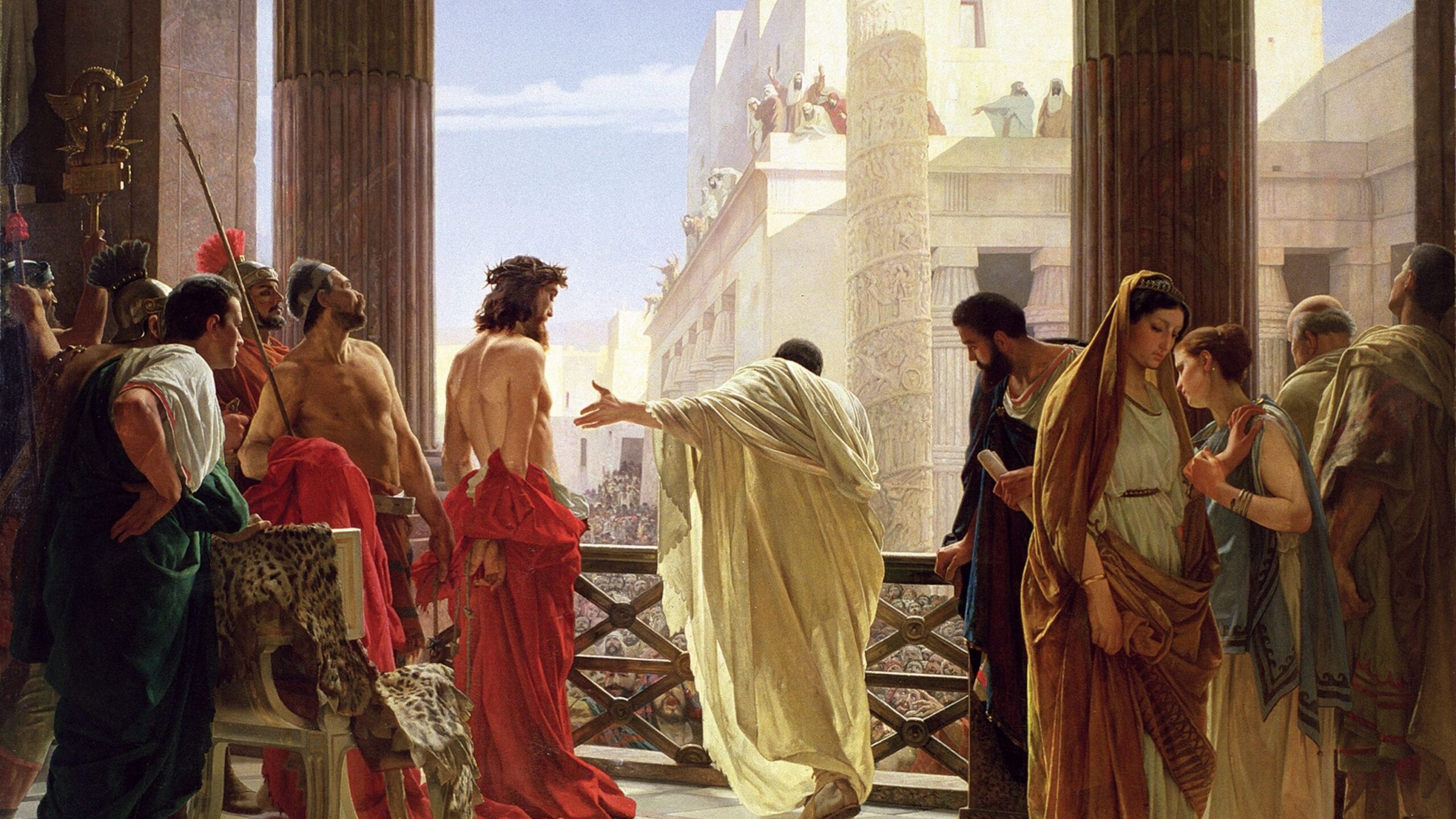

Few scenes in the Bible can match the dramatic intensity of Christ’s encounter with Pontius Pilate. For me, as a political writer, this scene is both captivating and terrifying, and I return to it again and again in imagination.

Condemned and standing before the appointed emissary of Rome, Jesus is supposed to be the one awaiting judgment. But no mere human can truly judge God, as he himself clearly explains to the hapless Roman prefect. Earthly authorities have exactly as much power as the Lord has chosen to allow. In a very real sense, it is the state that here stands in judgment before Christ. It is found wanting.

Pilate is impressed by Jesus. He is accustomed to dealing with men of consequence, so he easily perceives the power and gravitas of his prisoner. This perplexes him. People brought to Pilate for judgment probably did not, in general, show much composure; they were likelier to rage, cower, or flatter. Jesus does none of these things. He fields questions coolly and adroitly, explaining that he is not a political leader but came instead to “bear witness to the truth. Everyone that is of the truth hears my voice.”

Overwhelmed by the intensity of the conversation, Pilate bails. “What is truth?” he asks, and walks out without waiting for an answer. Despite his brief flicker of curiosity, Pilate in the end is a typical politician. Standing in the presence of omniscience, he could have asked any question at all, but instead he chose to run.

It turns out that the honor of serving the truth isn’t just there for the taking. It must be earned.

We see the same pattern often in our own world. Indeed, in some noteworthy ways we live in a society very much like Jesus.’ At the time of the Gospels, Israel is not enslaved, as they were to Egypt or Babylon, nor forbidden from worshiping the true God, as in the books of Maccabees. But she is afflicted by great turbulence and doubt. Confused and drifting, people desperately seek guidance and fall prey to factions, fantasies, and false prophets. Politicians scheme and manipulate, while vendors hawk products even in the temple itself. The Israelites are “like sheep without a shepherd.” Living in twenty-first-century America, it all sounds grimly familiar.

Pundits and commentators today sometimes comment that our society, especially in the political realm, is “post-truth.” In an immediate sense, they mean that we have access to an abundance of both information and misinformation, with too few reliable authorities to help us distinguish. In that environment, we are easily led astray. Influencers appease our vanity, while demagogues stroke our resentments; authoritative spokesmen tell lies to manipulate public behavior, seemingly without shame. It becomes very difficult to determine what is true.

There is also a deeper sense in which the world today often feels “post-truth.” Some clear and obvious truths, familiar to nearly all humans since time immemorial, are suddenly controversial in our time, or perhaps in some spheres even impermissible to speak. Families are good. God should be honored. A human being is either male or female, and it takes one of each to make a child. Everyone used to know these things, but today nothing seems certain. What is truth, anyway?

Would-be evangelists have our work cut out for us. This was one consideration that drew me into public writing in the first place (roughly twelve years ago), and as a fledgling opinion writer, I felt remarkably little anxiety over the business of figuring out what was true. In such a deeply confused world, there seemed to be plenty of low-hanging fruit. My job was to speak the truth with boldness! I can still remember a time when writing cultural and political commentary felt like a delightful romp.

Lord, make me worthy to say something true.

The post-truth world is not escaped so easily. This became increasingly clear to me as I got to know other writers and journalists, and noticed how some of them (including, uncomfortably, people who shared many of my views) seemed to strategize endlessly about the best routes to coveted worldly prizes. If they could be published in this outlet. If they could connect with that important media personality. Reaching such-and-such a number of Twitter followers would mean that they had arrived.

Not all writers are like this, but it was still jarring to see how completely petty ambition could come to dominate a person’s horizons. Did truth fit somewhere into this picture? How was that properly weighed against a thousand new followers or a prestigious television spot?

Before I had finished processing this professional world, it was hit by an 8.5-level earthquake, and all the clever plans (electoral, political, personal) were thrown into disarray. This was in 2016. The political right was dramatically upended, and for a time it seemed necessary, every time I talked to a friend or colleague, to “take a sounding” on their views, which might bear little resemblance to what they claimed to believe a few weeks or even days before. Indeed, last month’s views might be anathema to them now. Needless to say, this was a bitter and disillusioning time. I thought about George Orwell’s 1984. I thought about the people in Jerusalem who cried “Hosanna!” on Palm Sunday and then “Crucify him!” just a few days later. I thought about quitting and writing children’s books.

In the end that didn’t happen, but the bruising experience forced me to confront the question of truth with much greater seriousness. I had to revise my opinion of some people I had once respected, but the most crucial insights really weren’t about other people but about myself. Considering the matter honestly, I had to acknowledge that I was not immune to any of the failings that I could see leading others astray. I too crave earthly opportunities and honors; I enjoy applause and approval; I like feeling unimpeachably right when those people over there seem clearly wrong. I don’t love admitting my own mistakes. Maybe I’m part of the problem? Have I helped lay bricks for a post-truth world?

We need to ask this question of ourselves and return to it regularly. It’s pleasant to imagine ourselves as stalwart warriors for truth, whether we write articles, post thoughts on social media, or just expound on our views over Sunday dinner. But like most worthwhile things, it turns out that the honor of serving the truth isn’t just there for the taking. It must be earned. We must allow God’s grace to shape us into the kinds of people who can both see and tell the truth, even in a desperately confused society. That means examining our consciences closely, considering who we most want to influence or impress, and whose influence we most want to be under (and why). Those questions will sometimes have uncomfortable answers. But if we really want to spread the light of Christ, we must strive continually to grow in holiness, confessing our failures and praying earnestly, “Lord, make me worthy to say something true.”

Despite his cynical question, Pilate was not entirely uninterested in the truth. He recognized that Jesus was both important and innocent, and he made a real attempt to avoid condemning him to death. The sign Pilate hung on the cross proclaimed a profound truth, though it’s unclear what the prefect himself really believed. In the end though, truth was not Pilate’s top priority. He valued politics more. He was cowed by the factional fury of a world that, like ours, struggled to separate fact from fantasy. Under pressure, he caved.

Most of us do, at least sometimes. In a post-truth society, it often feels as though it doesn’t really matter. What is truth anyway? When the social and political order becomes sufficiently detached from any reliable source, it starts to feel permissible to prioritize other things. Maybe we care more about political objectives, personal survival, or the protection of people or things we love.

We shouldn’t fool ourselves. Even after Pilate leaves the room, Truth still stands behind him, undiminished. He is the way to the only objective that is really worth attaining. And only those “of the truth” will hear his voice. So turn around, and listen.