One of our deepest desires as human beings is a desire for home—a place where we can count on being loved and valued, a place where we will always be welcomed, a place where we can truly feel we belong. Unfortunately, modern culture has made the experience of home an increasingly elusive one. Which is one of the reasons why so many people in contemporary society feel isolated and lonely. Roger Scruton, the British philosopher and social commentator, has observed that this loneliness and sense of isolation have become so pervasive that much of our modern literature, art, and music now focuses on the isolated individual and his search for home and community or his “lapse into solitude and estrangement.”

Where can we find a lasting experience of “home”? For many of us, our deepest experience of home in this life is found with our family. But throughout the ages, we have also experienced a sense of “home” from a variety of other sources, including our identity as a citizen of a particular country, our membership in a specific culture, our connection to the natural world, and our relationship with God. Tragically, modern culture has systematically undermined every single one of these potential sources of “home”:

FAMILY

There have been too many assaults on the traditional family to list all of them here, but they include abortion; no-fault divorce laws; social welfare policies that financially disincentivize marriage and instead incentivize single parenthood; the re-definition of marriage, with that re-definition being enforced by the punitive power of the state; political “progressivism,” which seeks to undermine parents’ rights to raise children in accordance with their own values; and other political ideologies that do not seek merely to undermine the traditional family but rather to completely destroy the family, viewing the family as the last major obstacle standing in the way of the state’s ability to exert total control over the lives of its citizens.

For millennia, human beings have found a sense of home in their connection to the specific geographic area in which they live.

REGION/NATION

For millennia, human beings have found a sense of home in their connection to the specific geographic area in which they live. Today, many of our cultural elites frown on this connection to place, seeking to discourage or even ridicule such attachments and the patriotism that is an expression of this attachment. Witness, for example, the anti-American sentiment being foisted upon us and our children by the mainstream media and by many teachers and professors at all levels of the educational system in the United States. Some globalists seek to blur, and perhaps even eliminate altogether, the national boundaries that have helped to serve as a source of identity for so many people for so long. Well-defined borders, accompanied by reasonable and humane immigration policies, help to sustain a nation’s identity and thereby help to sustain an important source of identity and “home” for its people. Can nationalism be taken to excessive lengths? Yes, of course; but the solution is not to eliminate nations entirely in favor of a single world government, as is envisioned by some globalists (in which case, one wonders what would serve as a check on the power of such a government over its citizens), but rather to strive for moderation with regard to nationalism and patriotism, as in all things. The “citizen of the world” who will supposedly feel at home everywhere will, in fact, likely feel at home nowhere.

CULTURE

Many of our cultural elites feel a disdain for Western culture similar to their disdain for patriotism. In both Western Europe and the United States, one frequently finds people who harbor an actual hatred for the culture that gave birth to, raised, and still supports them. At its root, this hatred for one’s own culture often seems to arise from a certain amount of self-hatred, but that’s an essay for another day. Our cultural elites and our public education system have largely rejected the canon of Western literature, art, and thought that constitute the heart of Western culture, and they seem bent on teaching future generations to hate and reject that culture as well. As I have written about elsewhere, one of the most corrosive trends in contemporary culture has been its growing tendency to reject some of the most fundamental—and significant—aspects of human existence (indeed, of existence itself): truth, beauty, and goodness. We human beings have a deep desire, even need, for truth, beauty, and goodness, and a culture that deprives its citizens of these all-important qualities cannot continue to feel like “home” for its members in the long run.

NATURE

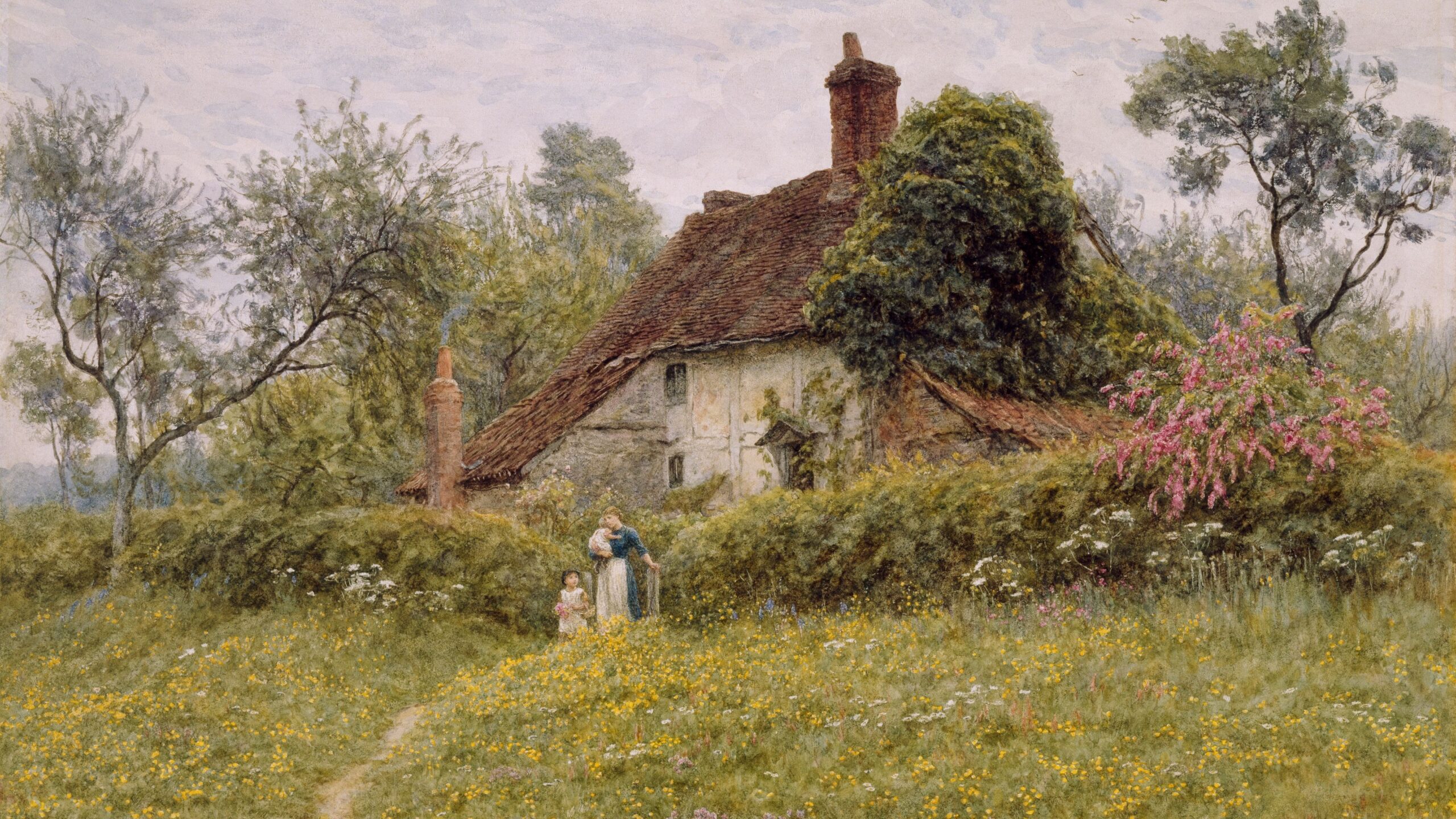

The natural world has long been a source of “home” for us human beings—that’s one of the reasons so many of us enjoy being “out in nature”: gardening, hiking, camping, etc. That’s also one of the reasons we have so often chosen to portray nature in our works of art, as Scruton points out: “From the earliest drawings in the Lascaux caves to the landscapes of Cézanne, the poems of Guido Gezelle and the music of Messiaen, art has searched for meaning in the natural world. The experience of natural beauty is not a sense of ‘how nice!’ or ‘how pleasant!’ It contains a reassurance that this world is a right and fitting place to be—a home in which our human powers and prospects find confirmation” (emphasis added). But modernity hasn’t left this source of home alone, either. Philosophical materialism, the view that everything, including human beings, is nothing but the random swirl of atoms, reduces everything, including us human beings, to mere objects. Admittedly, materialism is not an entirely new worldview, since ancients such as Democritus, Epicurus, and Lucretius all professed this view, but materialism has become an increasingly popular outlook in recent decades, in part because of its advocacy by scientists such as Richard Dawkins. Scruton argues that by reducing all of nature, including ourselves, to mere objects, materialism has “disenchanted” nature. Nature (including the human body) no longer feels like “home” to some of us, but rather is now viewed as merely something to be manipulated, controlled, and altered so that it can be directed completely toward the fulfillment of human desire. Nature, especially the beauty and sublimity we find in so much of nature, used to point us toward something deeper, something higher: toward transcendence; toward the sacred; toward God. Nature, and all of the other earthly sources of “home” (family, country, culture, etc.), used to point us toward our real home, our deepest home, our permanent home—our home in God. These days, for many people, not so much—partly because of modernity’s assault on each of those potential sources of home, and partly because of modernity’s direct assault on religion itself, its persecution of religious believers (prejudice against Christians and Jews is still permitted by, and even condoned by, many among our “cultural elites”), and its rejection of the very existence of God.

What we really long for is not to be dissolved in God, but rather to participate in God, to share in the divine life of God while still maintaining our existence as individual persons.

GOD

As a unity of body and soul, we human beings are “boundary phenomena”: we straddle the boundary between the purely physical and the purely spiritual. That is one of the reasons why we can never feel completely “at home” in nature: in this sense, we are “in” the world but not entirely “of” the world. Hans Urs von Balthasar eloquently expressed this reality: “Man is indeed experienced as a ‘frontier’ between this world and the world above, as one who cannot feel completely at home in the cosmos and is haunted by a longing to return to the Absolute.” Scruton described our condition in this life as one of “metaphysical loneliness” or “existential loneliness”: as self-conscious and rational beings, we feel somewhat isolated and disconnected from the rest of the physical world. We are subjects, not just objects, but we find ourselves surrounded by a world of objects and thus do not feel entirely “at home” here. Scruton claimed that our metaphysical loneliness reflects “a longing to be dissolved in the subjectivity of God.” He was on the right track, but what we really long for is not to be dissolved in God, but rather to participate in God, to share in the divine life of God while still maintaining our existence as individual persons. And that is, in fact, what God offers us in Jesus Christ:

His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, that through these you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of passion, and become partakers of the divine nature.

(2 Peter 1:3-4) (emphasis added)

This is what God wants for us; this is the purpose for which God made us: that we might share forever in the divine life of God through Jesus Christ, and thereby also share forever in the divine love and bliss. Christian tradition has referred to this process by which we come to participate in the divine life by various names, including divinization, deification, theosis, and incorporation. One of the terms Balthasar preferred was Heimkehr, which is German for “homecoming.” Life in God will be our ultimate “homecoming.” Only when we are in the Father’s house will we finally and truly be home (John 14:2). The Father’s house is the home for which we have been searching. Life in God is our true home, the home for which we were made, the home in which we will find our ultimate happiness and peace. And this physical world, this world which we presently feel “in” but not “of,” will be transfigured and transformed and brought with us into the divine life of God forever (Rev. 21:1-4).