When he was just twelve years old, the pious child, Rajmund Kolbe (born in Zduńska Wola, Poland, a subject of the Russian Empire) had a vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which he later described to his Franciscan Superiors thusly:

That night, I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me, a Child of Faith. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.

It is fitting that we today anticipate Saturday’s Feast of the Assumption of Mary by remembering a saint whose devotion to the Blessed Mother informed and inspired a heroic life lived energetically—and subversively—for Christ. Just last weekend, we remembered and honored the great Carmelite philosopher and saint Edith Stein, who was killed at Auschwitz, and today we remember another highly educated twentieth-century martyr, the great Franciscan friar (and philosopher, theologian, astro-physicist, and publisher) Rajmund Kolbe—in religion, Maximilian Mary Kolbe.

Maximilian Kolbe was a Polish priest who died as prisoner 16770 in Auschwitz, on August 14, 1941. When a prisoner escaped from the camp, the Nazis selected 10 others to be killed by starvation in reprisal for the escape. One of the 10 selected to die, Franciszek Gajowniczek, began to cry: My wife! My children! I will never see them again! At this Maximilian Kolbe stepped forward and asked to die in his place. His request was granted.

In fact, what Kolbe said was, “I am a Catholic priest. Let me take his place. I am old. He has a wife and children.”

A Catholic priest! How could evil refuse such an offer? Gajowniczek was spared. The prisoner Kolbe was instead taken.

He is greatly remembered for his self-sacrifice in Auschwitz—and there is so much greatness to read of, from the testimony of eye-witnesses. Here is Bruno Borgowiec, a Pole assigned to serve the starvation bunker:

The ten condemned to death went through terrible days. From the underground cell in which they were shut up there continually arose the echo of prayers and canticles. The man in-charge of emptying the buckets of urine found them always empty. Thirst drove the prisoners to drink the contents. Since they had grown very weak, prayers were now only whispered. At every inspection, when almost all the others were now lying on the floor, Father Kolbe was seen kneeling or standing in the centre as he looked cheerfully in the face of the SS men.

Father Kolbe never asked for anything and did not complain, rather he encouraged the others, saying that the fugitive might be found and then they would all be freed. One of the SS guards remarked: this priest is really a great man. We have never seen anyone like him.

Two weeks passed in this way. Meanwhile one after another they died, until only Father Kolbe was left. This the authorities felt was too long. The cell was needed for new victims. So one day they brought in the head of the sick-quarters, a German named Bock, who gave Father Kolbe an injection of carbolic acid in the vein of his left arm. Father Kolbe, with a prayer on his lips, himself gave his arm to the executioner. “Unable to watch this I left under the pretext of work to be done. Immediately after the SS men had left I returned to the cell, where I found Father Kolbe leaning in a sitting position against the back wall with his eyes open and his head drooping sideways. His face was calm and radiant.”

Another survivor, Jerzy Bielecki, called Kolbe’s action “a shock filled with hope, bringing new life and strength. . . . It was like a powerful shaft of light in the darkness of the camp.”

Imagine someone saying that about you, about your faith and how willing you were to put your life behind it—to be the subversive, counterintuitive conduit of light amid great darkness.

One subject, one prisoner, that totalitarians in any age cannot defeat is the spiritually subversive—those who understand that whatever may be wrought against the body, the spirit made free in faith cannot be tamed. It will, instead, slip through the bars of containment, evade the clubbing of an authoritarian bully, because the person of faith’s great weapon of prayer cannot be boxed away, or stored among possessions, or limited, or rendered ineffectual.

The prayer of a person of faith is the weapon of a true subversive, and Maximilian Kolbe was nothing if not that.

He’d been arrested, in part, for hiding and assisting Jews—two thousand of them. Subversive. He consented to being thrown into a hole and starved to death; he asks for nothing, makes no anticipated pleas. Subversive. He remains cordial and relies wholly on hymns and prayers and psalms and canticles. There is such untouchable power in all of that. Subversive—and victorious.

The worldly call faith “stupid” and mock it. That’s why the worldly will ultimately lose, whatever the battle. No war is ever won by those who discount the weapons available to whom they would repress.

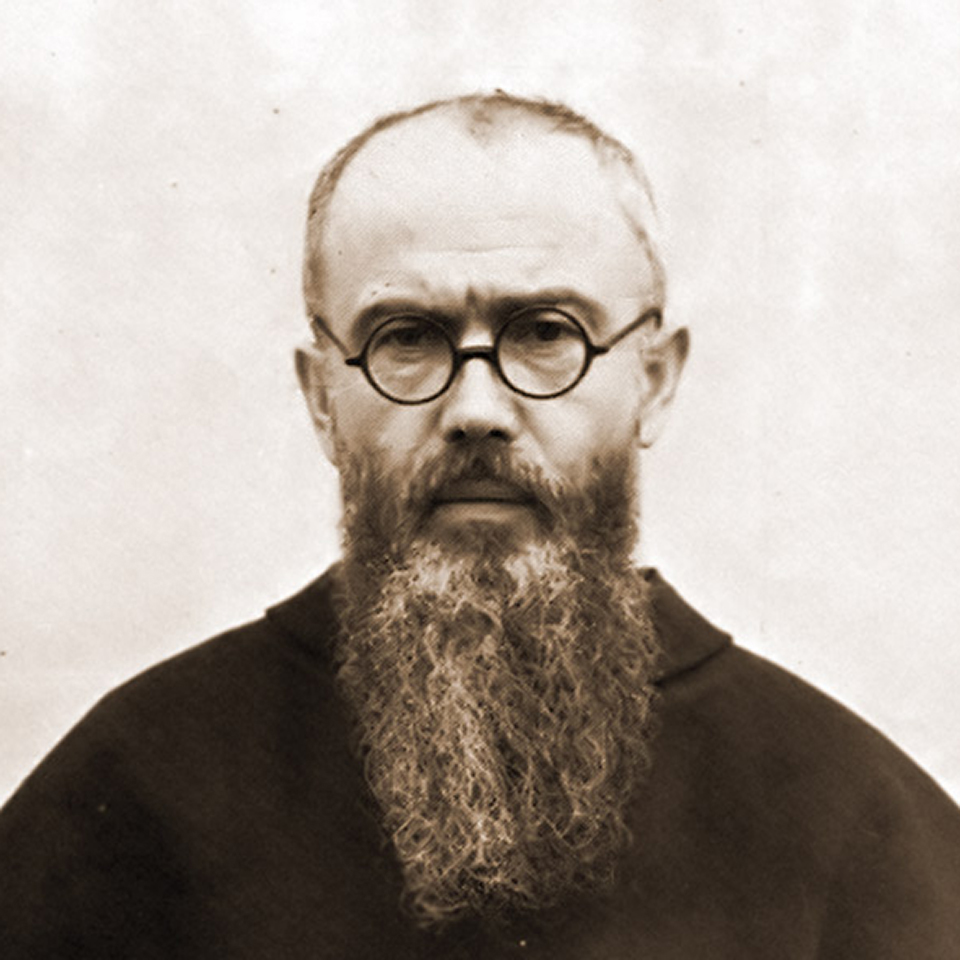

I have an image of Kolbe set before me. Every time I see his good, open face, I feel him asking me, “And what small thing—what small, subversive thing—have you done today, Elizabeth, to counter the empty illusions of the world and advance the kingdom of heaven?”

St. Maximilian Kolbe, ora pro nobis.