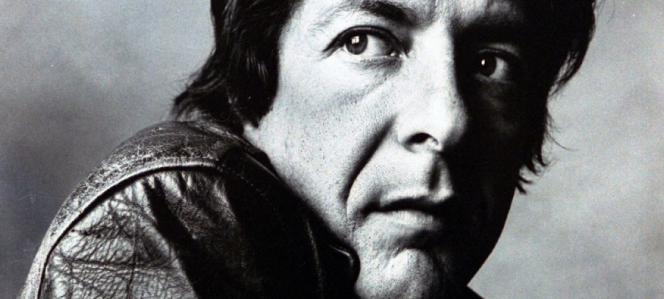

So this week while I was out of town staying at a hotel, I happened on an article about singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen’s Jewishness and how it impacted his music. Knocked my socks off. I had heard his famous Hallelujah, but was not aware of his other music. Now I am. I wrote a journal entry late at night on a song from his final album. I won’t bother editing or cleaning it up. It is what it is. It’s heavy.

Cohen’s music is searching, pained, edgy, gritty, socially engaged, and religiously dissident, but he relentlessly clings to a Jewish biblical landscape. It was his Judaism, eclectic as it was. Right to the end of his life, he inhabited and was inhabited by his Hebrew faith—its language, worship, narratives—as he grasped for meaning at the very edge of meaning. At the edge of the grave, his grave. This was one of the final songs written and recorded just before his death in 2016. It utterly captivated me last night: “You Want It Darker.” I dreamt of it and then woke up at 3:00 a.m. to write.

I wish I could explain the inner sense of awe and holy fear I felt as I awoke.

Cohen’s gravelly voice bears all of the gravitas of a man near death, weakened by the decay of his aging body. Haunting.

There’s so much going on in it. The song, addressed to God as “you,” is suffused with the language, and tones, of the Kaddish—Jewish prayers for the dead.

Cohen wants his poetry to find its luminescence beneath the long shadows that arc over the atrocities of history—especially those perpetrated against Jews, intended to extinguish the flame of their existence from the earth.

He invokes in the song what seem to be phrases from the story of the “binding of Isaac” in Genesis 22, when God commanded Abraham to slaughter his beloved son, Isaac. The Hebrew word Hineni, which means “Here I am,” is repeated thrice in the “You Want It Darker” song and in Genesis 22 (vs. 1, 7, 11).

God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.” (Genesis 22:1-2)

This is the first but not last time it appears in Scripture.

Hineni punctuates this song’s dread reckoning with God’s seeming complicity with darkness and murder in the Isaac story. Cohen grapples with the meaning of God’s “permissive will,” allowing evil space in creation. Or is it his ordained will with Abraham? Allowing death such immense power in the world, through the bloodstained hands of every Cain, his own image. Man.

“Man! What a novelty, a monster, a chaos, a contradiction, a prodigy! Judge of all things, an imbecile worm; depository of truth, and sewer of error and doubt; the glory and refuse of the universe.” (Blaise Pascal)

Hineni resonates with obedient readiness. It is what a faithful Jew says to God when summoned and called, even in the face of the “valley of the shadow of death.” But Cohen is not so willing to embrace this word in the face of such deep darkness. Indeed, he “wants out” if thus is how the Dealer deals. He will not simply submit without protest against death, without shouting out from within the dark mystery that enfolds humanity.

Cohen contends with God, like Abraham at Sodom (Genesis 18:16-33), like Jacob at Jabbok (Genesis 32:22-32), like Moses in the desert (Exodus 32:9-14), like Job in anguish (Job 31), like Jeremiah in terror (Jeremiah 20:7-18; Lamentations), like Esther facing genocide, like the psalmists crying out from the suffering of catastrophe, exile, slaughter.

“Will the Lord reject us for ever?

Will he show us his favor no more?

Has his love vanished for ever?

Has his promise come to an end?

Does God forget his mercy

or in anger withhold his compassion?”

I said: “This is what causes my grief;

that the way of the Most High has changed.” (Psalm 77:8-11)

Cohen refuses to accept the image of a God complicit in injustice and evil, even if by permission.

Hard stuff.

Undoubtedly the Holocaust, along with its countless modern genocidal analogues, looms large in his mind as he, a Jew, writes, recites, sings—prays—this song.

When Cohen says, “Hineni. I’m ready my Lord,” what does he brace himself ready for?

Unresolved.

“Vilified, crucified in the human frame.” Easy to imagine in this a Christian meaning. But for a Jew, the very fact that God’s image is marred by human cruelty causes insufferable dissonance. A shattering paradox, as divine image slays divine image. Genesis 9:5-6. The slaughter-bench of history’s endless procession of image-smashing murderers, permitted to “murder and maim.”

Why is such horrifically expansive latitude given to evil? How does this work in a divine economy? A paradox to blame? But what comes of this paradox’s unresolved tensions? Is their a deeper protest at work in God himself?

“Why?” (Psalm 22:1)

The song is just brilliant: raw, shocking honesty, protest in the face of the dark night of evil—spoken before the face of God. It does not sound to me as rebellion, but a laying before God the cursed evil without submitting it to an easy resolve. Not cushioned, romanticized, coated, softened, but prayed out of dark faith into God.

Like the absolutely stunning Psalm 88, the only unresolved lament among all the psalms. The psalmist ends his for God’s place in the chaos in the night, moaning beneath heaven’s dead silence. Or the Book of Lamentations, which makes your heart sweat if you really pray into it, especially at night. Why don’t we have this oft in the Lectionary for Sundays? We human-wailers need its honest desperation turned Godward.

I am the man who has seen affliction under the rod of his wrath; he has driven and brought me into darkness without any light; surely against me he turns his hand again and again the whole day long. He has made my flesh and my skin waste away, and broken my bones; he has besieged and enveloped me with bitterness and tribulation; he has made me dwell in darkness like the dead of long ago. He has walled me about so that I cannot escape; he has put heavy chains on me; though I call and cry for help, he shuts out my prayer; he has blocked my ways with hewn stones, he has made my paths crooked. He is to me like a bear lying in wait, like a lion in hiding; he led me off my way and tore me to pieces; he has made me desolate; he bent his bow and set me as a mark for his arrow. He drove into my heart the arrows of his quiver. My soul is bereft of peace, I have forgotten what happiness is; so I say, “Gone is my glory, and my expectation from Yahweh.” (Lam. 3:1-14; 17-18)

Such is prayer for those who “descend into hell.” Prayer de profundis, “out of the depths” (Psalm 130:1). In the abyss, hope shines brightest. Hope blooms fullest only in hopeless spaces, in fathomless oceans requiring infinite anchors.

And God cannot redeem what he does not make his own, what we refuse to surrender to him—the meadows and the sewage. Prayer that emerges from such a radical depth of honesty is that of very few, it seems to me—those from whom all has been taken. But it alone achieves a depth of redemption that, as St. John of the Cross says in the Dark Night, makes the entire creation shake to its foundations. Sanatio in radice, “healing in the roots.” Jesus prayed this way from the cross: “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani!”

Cohen is voicing prayer for the prayer-less, those paralyzed spirits who sink into the pit, are mired in PTSD, breathe death in the gas chamber, suffer.

Why? Where? How long? Wake up! Act! Save! Come! No facile answers to the mystery of iniquity. No easy comforts wrapped in smiley tinsel. Only wailed protests for justice, cries for mercy that, after they are drained to the dregs, surrender. Hineni.

Pope Benedict, son of Germany, said at Auschwitz:

To speak in this place of horror, in this place where unprecedented mass crimes were committed against God and man, is almost impossible—and it is particularly difficult and troubling for a Christian, for a Pope from Germany. In a place like this, words fail; in the end, there can only be a dread silence—a silence which is itself a heartfelt cry to God: Why, Lord, did you remain silent? How could you tolerate all this? In silence, then, we bow our heads before the endless line of those who suffered and were put to death here; yet our silence becomes in turn a plea for forgiveness and reconciliation, a plea to the living God never to let this happen again.

David Bentley Hart, reflecting on the 2004 Indian basin Tsunami that claimed more than 230,000 lives across 14 countries, said:

As for comfort, when we seek it, I can imagine none greater than the happy knowledge that when I see the death of a child I do not see the face of God, but the face of His enemy. It is not a faith that would necessarily satisfy Ivan Karamazov, but neither is it one that his arguments can defeat: for it has set us free from optimism, and taught us hope instead. We can rejoice that we are saved not through the immanent mechanisms of history and nature, but by grace; that God will not unite all of history’s many strands in one great synthesis, but will judge much of history false and damnable; that He will not simply reveal the sublime logic of fallen nature, but will strike off the fetters in which creation languishes; and that, rather than showing us how the tears of a small girl suffering in the dark were necessary for the building of the Kingdom, He will instead raise her up and wipe away all tears from her eyes—and there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying, nor any more pain, for the former things will have passed away, and He that sits upon the throne will say, “Behold, I make all things new.”

God who suffered, was crucified, died, was buried, descended into hell, and rose again from the dead.

“The limit imposed upon evil by divine good has entered human history through the work of Christ.” (Pope Benedict XVI)