Last week on vacation, I climbed the highest mountain in Ireland. It was an experience that was physically rewarding but even more so spiritually. Knowing that every other person in the country was below me with only God above me was a wonderful moment of awareness and gave me an opportunity to intercede for all the people of the nation. The spectacular views on display while climbing gave a sense of true perspective; I was struck with wonder before the beauty of God’s creation. Near the top of the mountain, the light was suddenly blocked out as we entered into a thick cloud. Despite the loss of light and impaired visibility, we just kept climbing, one step at a time. Eventually, the shape of a large metal cross emerged before us, which marked our arrival at the summit. There, I prayed the fourth Luminous Mystery of the Rosary, the Transfiguration, the feast that the Church celebrates tomorrow.

In Scripture, God reveals himself on mountaintops. In the Old Testament, God gave Moses the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, and in the New Testament, Jesus gives us the Beatitudes after “going up a hill” (Matt. 5:1). Jesus died on the hill of Calvary, where the fullest revelation of his saving love took place. With the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, we have the revelation of Jesus’ divinity that shone through him as a blinding light for Peter, James, and John to behold (Matt. 17:1-9; Mark 9:2-10; Luke 9:28-36).

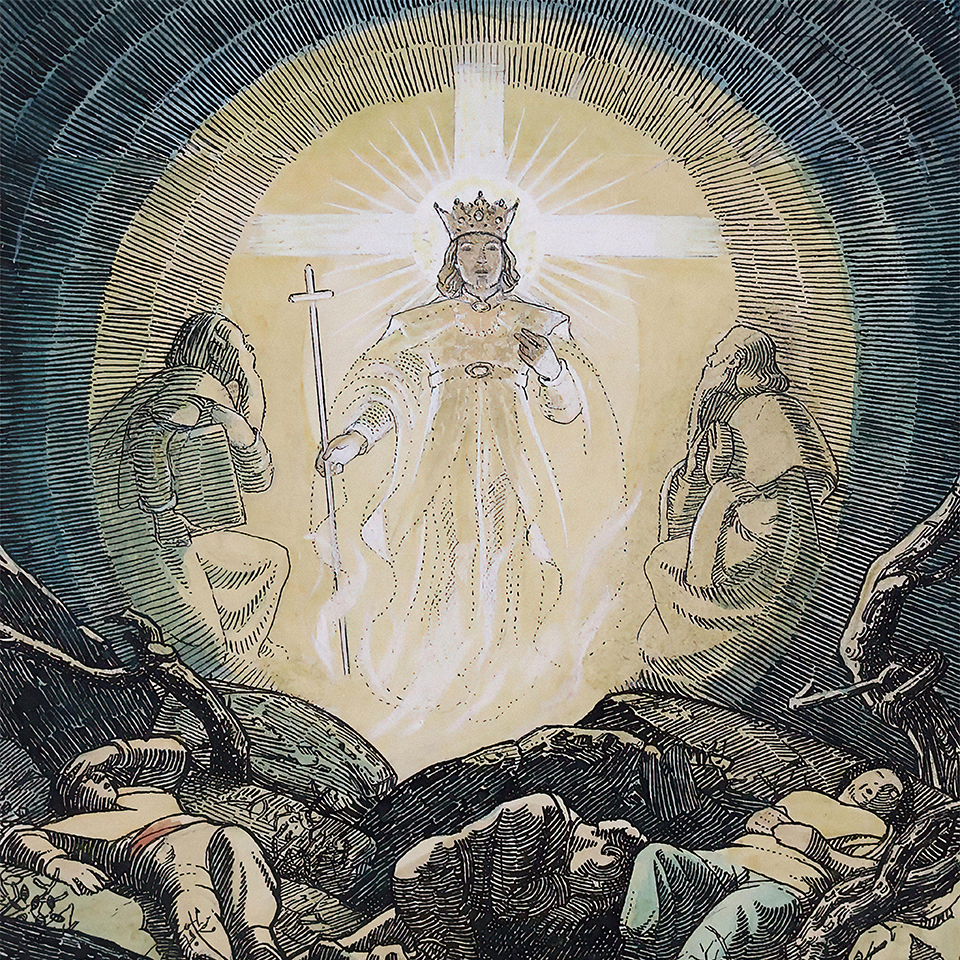

The image that the Gospels use to convey the Transfiguration is light. Jesus’ face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white. This is appropriate, for light allows us to see what is already there. Jesus was always divine, but people could not always see his divinity. On the top of Mount Tabor, it became clear to Peter, James, and John who Jesus truly was: “God from God” and “Light from Light,” as the Nicene Creed tells us. This light shone out from his humanity and concrete existence. God’s light shone through him and not apart from him. This point is crucial as we understand our lives in Christ. God’s grace and light shine through our humanity and make it radiant in transfiguration. Our faith in Christ is not an obstruction to living a fully human life; it is the source of living a fully human life.

This radiant light from Christ has the peculiar quality of attracting those who behold it and illuminating the beholder with its brightness. We think here of Moses who “as he came down from the mountain, did not know that the skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God” (Exod. 34:29-35). Exposure to God’s light communicates some of that light to us.

In the early Church, St. Basil declared that the Holy Spirit shines on believers and “illuminates them like the sun” (On the Holy Spirit, 26.61). For St. Irenaeus, the light of Christ that shines on us both penetrates us and enfolds us: “The light of the Father passes into the flesh of Christ; and from Christ it shines forth upon us, so that each of us is enfolded” (Against Heresies, 4.20.2). He goes further to say that as we behold God’s light, we come to partake in it: “Just as those who see the light are within the light and participate in its splendor, so those who see God are within God and participate in his splendor” (Against Heresies, 4.20.5).

The implications of this are immense. It means that when we encounter God in prayer and participate in the liturgy, we are absorbed into his light and become luminous with it. Like Moses, this illumination happens whether we are aware of it or not. St. John Chrysostom was convinced that “it is easier for the sun not to give heat and not to shine than for the Christian not to send forth light” (Homily on the Acts of the Apostles, 20.4).

At our Baptism, our parents received our baptismal candle that was lit from the Paschal candle. This gesture symbolized the truth described by C.S. Lewis, that “we are mirrors whose brightness is wholly derived from the sun that shines upon us” (The Four Loves). We have been enlightened by Christ. Therefore, when Jesus calls us to be “the light of the world” (Matt. 5:14), it is his light that we are called to radiate and not our own. He commissions us to be bearers of his own light into the arenas where we find ourselves—into the great spheres of culture, such as education, entertainment, politics, sport, the internet, family, school, university, and parish life, to name but a few. In these places, we are called to carry Christ’s light so that others might be attracted to that light too. With the encouraging words of St. Paul, we are to “walk as children of light” (Eph. 5:8).

This is what it means to be holy. Holiness is to take on the nature of Christ and to become luminous with his grace. That is why many representations of the saints in sacred art display them with a halo around their heads and bodies. At the Transfiguration, Jesus’ radiance with the light of heaven entices us and excites us with the prospect of our own transfiguration in him.

There is, however, another feature of this divine light that I was reminded of as I reached the summit of the mountain. The experience of the disciples was that of light, but lurking around the edges of the story is darkness and suffering. There is a parallel between the luminous glory of Tabor and the terrible darkness of Calvary that was to follow. Yet for John in his Gospel, God’s glory shone out from this terrible darkness with the greatest love that the world has ever known. Being enlightened by Christ does not mean that we are spared from times of darkness and suffering. Like walking in the thick cloud near the summit of the mountain, there are times when all we can do is put one foot in front of another, keep trusting, and keep walking.

Furthermore, participating in Christ’s light is not about a constant search for consoling luminous experiences. There are moments of darkness that we all need to contend with. Experiencing God is not about leaving darkness behind so as to obtain light; it’s about allowing God’s presence in the dark to purify our egos and free us from possessive desire. In this way, we seek not the consolations of God but God himself. Bishop Barron refers to this path of holiness as “knowing you are a sinner.” Encountering God’s light leads to a necessary grappling with our own darkness and imperfections. Divine light is disconcerting, but it humbles our pride and frees us from possessive desire in a way that changes us to become more radiant images of Christ himself. In the words of St. Peter as he interpreted his experience on Mount Tabor: “You will do well to be attentive to this as to a lamp shining in a dark place until the day dawns and morning star rises in your hearts” (2 Pet. 1:19).

On the Feast of the Transfiguration, we join in praise of the God who is light and who allowed that light to shine from the humanity of Christ on Mount Tabor. We give thanks for the gift of that light that we have received at Baptism and that we joyfully bear to all. As we navigate experiences of darkness and suffering, may we come to believe that God still loves us in the night as his grace purifies us, changes us, and unites us more deeply to himself.