God gave me parents more suited for heaven than this earth.

—St. Thérèse of Lisieux

I have been ministering to youth and young adults for more than a decade, and there seems to be overwhelming hopelessness. There are many reasons for this, but one of the most poignant comes shortly after asking them, “When is the first time you witnessed authentic love?” For many of them, it takes some time to respond to this, especially young adults.

I’ve met people in their twenties who can very much attest to only recently seeing love lived well, embodied even. It’s one of the greatest compliments when some have said the first time they witnessed it was in my home, with my husband or with our children. It’s humiliating (in a good way) but also saddening to know that sources of authentic love—primarily “good” examples of marriage and family—are rare.

There has been such degradation of family life today that the ripples of this are felt in society’s social fabric. Without fathers and mothers, we inevitably don’t know how to “become like little children.”

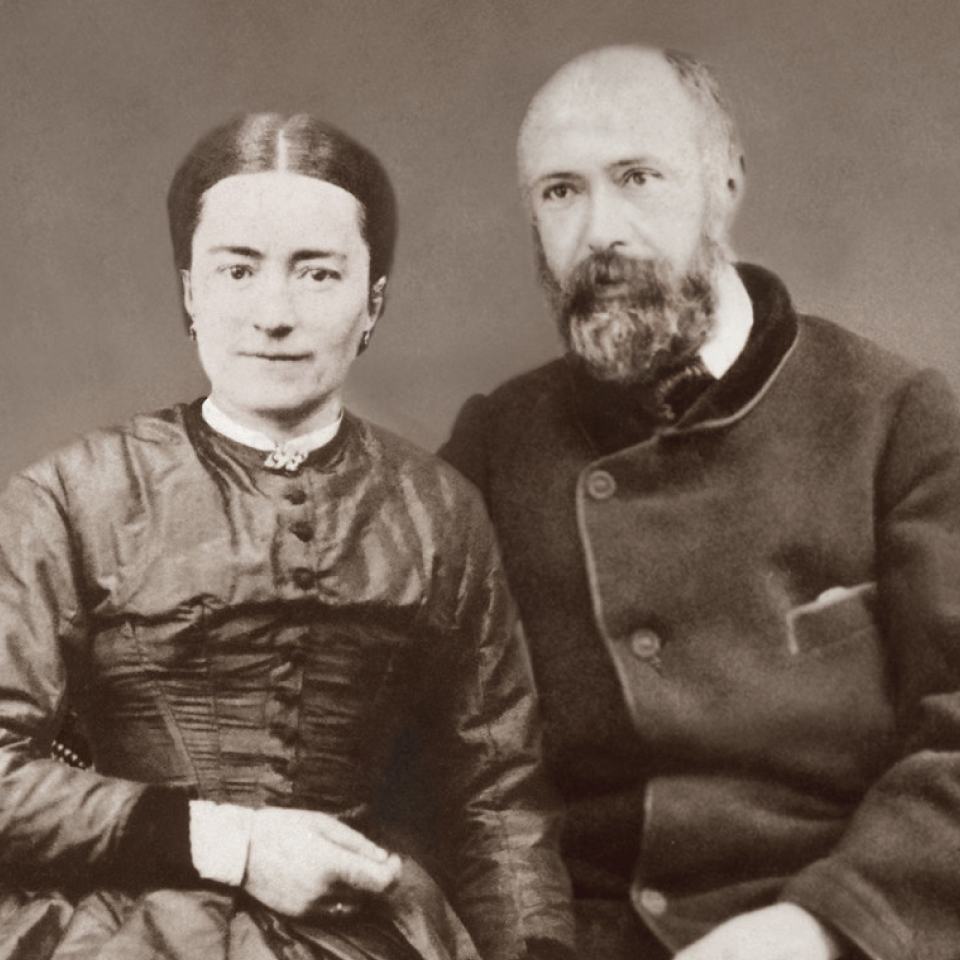

When I think of the “little soul” or childlike faith, my thoughts inevitably rest on St. Thérèse of Lisieux, and quite naturally, one would wonder if her parents had anything to do with her predisposition to become the “Little Flower.” Much can be attested to the grace of God, but one can also attribute his grace and love in giving her Sts. Louis and Zélie Martin as her parents.

They were canonized on October 18, 2015, as the first spouses to be canonized together. And they serve as beacons of hope to many looking for inspiration for marriage and the family.

It’s an incredible wonder to read about a man and a woman who loved one another deeply, had a beautiful thriving business together, had nine children, lost four of them to illness at young ages, aided and eventually buried their ailing parents . . . and did all of these weighty things while maintaining virtue and a genuine pursuit of Christian perfection.

Here is this ordinary man, a watchmaker, who once desired to enter the monastery, leading an ordinary life in Alencon, France. Then, there’s the ordinary woman, with a lacemaking business, who once desired religious life, living in the same town. Their paths cross, and Zelié recalls that she saw Louis on the street and heard an inner voice: ”This is the one I have prepared for you.”

They were married, and shortly thereafter, Louis sold his business to help with Zelié ’s lacemaking business. He managed the books and sought merchants to sell the lace. At times, as a gifted artist, he would draw the lace designs for Zelié to create.

The same patience that they used in their respective occupations poured out into their marriage. While Louis would travel for the good of the household and the business, Zelié would make the lace, care for their children, and Louis’ ailing father—all the while attending to prayer, going to daily Mass, and writing letters to one another. There are over two hundred letters from Zelié and a few from Louis. A few of the letters are between them but also to their children and from Zelié to her sister.

The letters are so rich with care for the other but also care for one’s own soul, reflecting on their own prayer lives and their relationships with God. When I read their words, nearly tangible peace seems to flow from them.

And what is it that makes their lives stand apart? I think it’s the “ordinary-ness” of it. Without any particularity, they are saints that were merely husband and wife, with jobs and children, with families that needed them, with tragedy and death—and each and every time not only did Zelié and Louis rise above earthly worry, but they transcended into a peace that only makes sense with divine hope.

In a five-year span, four of their nine children died: Joseph (1), Joseph-Jean-Baptiste (1), Hélène (5), and Mélanie (2 months). Zelié’s affection never waned, and she visited their graveside frequently while clinging to her faith. She wrote: “When I closed the eyes of my dear children and prepared them for burial, I was indeed grief-stricken, but, thanks to God’s grace, I have always been resigned to His will. I do not regret the pains and sacrifices I underwent for them.” She also writes that she doesn’t understand how anyone could’ve said that it would be better not having “gone through all of that,” and added, “They’re enjoying heaven now . . . I have not lost them always. Life is short, and I shall find my little ones again in heaven.”

Then there’s this fatherly, almost silent and St. Joseph-like presence of Louis. He was a man of devotion and a man who cared deeply for his household. Even with his travel for business and time with the family, he would intentionally find time for his Christian devotion and for other leisure, fishing, hiking, and the like. You could even ascertain that his love for leisure, true leisure based in his faith, is what directed his work.

Zelié eventually passed away from breast cancer, and Louis was left with the five girls. Realizing their need for a motherly influence, he sold all that they had in Alencón and moved to Lisieux with his brother and sister-in-law. What great sacrifice! He would even write to them saying, “Remember that this is very hard for me. Please do all that your aunt and uncle ask of you.” And he signed many of his letters with words like “your father who loves you.”

One of my favorite images of him comes from the writings of St. Thérèse. All of her sisters had shown desires to enter religious communities, and she remained. When her father came home after a trip, they walked up and down their garden with her head “very close to his heart,” and he held her “like a child” though she was already fourteen years old. And he received her desire for religious life and even helped her pursue it.

Isn’t that one’s desire as a parent? To allow a space for our children to always be children, a space to bring their deepest desires and be met with hope and means of purifying those desires for the highest good.

Louis eventually passed away after a long physical battle that resulted in the loss of his mind before his death. When he was lucid, he would say, “Everything for the greater glory of God,” and also, “I have never been humiliated in my life, I need to be humiliated.” And during his last visit to Carmel, he muttered these words to his daughters: “Goodbye, see you in Heaven!”

Yes, the civilization of love is possible; it is not a utopia. But it is only possible by a constant and ready reference to God, the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ, from whom all fatherhood in heaven and on earth is named (Eph 3:14-15), from whom every human family comes. (John Paul II, Letter to Families, February 2, 1994, No. 15)

Within the Martins’ life, we find hope not just for families but also for a certain rootedness that comes from it. Roots must be planted in that which provides means for life—not necessarily in one to the other or in geographical space, but most of all, in that which does not change: in God himself. The rootedness of the parents first flourished, building quite profoundly their own civilization of love. It proved to be fruitful ground for the vocations of their daughters and inspiration for the entire world.

Louis and Zelié were husband and wife and father and mother. But before all things, they were children of God. This constant revitalization of their filial identities is what oriented the life of their family, and is what inspires me as I read about their lives. Before I can properly be a wife or mother, I must always be a child before God.

Sts. Louis and Zelié Martin, pray for us! May we live by your great example to love one another, to love all that God has given us, and to always return to our greatest dignity as sons and daughters of God.