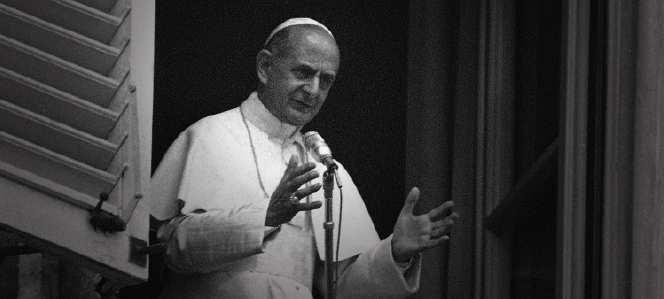

It is always helpful to notice references in writings, especially papal writings, and then be willing to explore those writings referenced. With a little digging you can be brought to some insightful, advantageous and even saving information. Since I wrote my post on the preacher as servant of dialogue I have done some digging into the writings of Bl. Pope Paul VI. Pope Francis references Paul VI quite extensively in Evangelii Gaudium. Specifically referenced is Paul VI’s 1975 Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi where the pontiff reflects on the Church’s responsibility of evangelization in the modern world. What I have found of interest though (and the purpose for this post) is an earlier writing of Pope Paul VI – his first encyclical, Ecclesiam Suam (ES) and its section on the work of dialogue.

In this encyclical, Paul VI explores how the world and the Catholic Church can meet one another and even get to know and love one another. (ES, 3) When considering how the Church should engage the world, Paul VI quickly discards the ever-present temptation to focus solely on the evils of the world and crusade against them as well as the desire to subjugate the world in a form of theocracy. Neither of these approaches will work. Rather, Bl. Paul VI concludes:

…it seems to Us that the sort of relationship for the Church to establish with the world should be more in the nature of a dialogue, though theoretically other methods are not excluded. We do not mean unrealistic dialogue. It must be adapted to the intelligences of those to whom it is addressed, and it must take account of circumstances. (ES, 78)

Paul VI then goes on to stress that this form of encounter is demanded due to dynamics prevalent within modern society – the understanding of the relationship between the sacred and profane, the pluralism of society and the maturity of thought men and women have attained in our modern world. I think it safe to say that gone are the days (at least here in the U.S.) when the priest is the most educated person in the room. But there is a deeper impetus for the discipline of dialogue and that is the respect it demonstrates. The willingness to dialogue by its very nature witnesses to a person’s esteem for the other as well as one’s own understanding and kindness. These are attitudes that every disciple of Christ, especially those called to the task of preaching, should cultivate and exemplify in life.

Our dialogue, therefore, presupposes that there exists in us a state of mind which we wish to communicate and to foster in those around us. It is the state of mind which characterizes the man who realizes the seriousness of the apostolic mission and who sees his own salvation as inseparable from the salvation of others. (ES, 80)

If we want dialogue then we, ourselves, must be willing to dialogue authentically and, not only that, the discipline of dialogue builds on dialogue. The preacher, as servant to dialogue, must be willing and, in fact, is duty-bound to work at fostering this discipline in our world today. Our world needs the discipline of dialogue.

Bl. Paul VI roots preaching in this greater task of the Church’s dialogue with our world:

Preaching is the primary apostolate … We must return to the study, not of human eloquence of empty rhetoric, but of the genuine art of proclaiming the Word of God. We must search for the principles which make for simplicity, clarity, effectiveness and authority, and so overcome our natural ineptitude in the use of this great and mysterious instrument of the divine Word, and be a worthy match for those whose skill in the use of words makes them so influential in the world today and gives them access to the organs of public opinion. We must pray to the Lord for this vital, soul-stirring gift… (ES, 90-91)

Paul VI then goes on to list out the proper characteristics of dialogue and, if proper for dialogue, then proper for preaching as the preaching task flows by nature out of the greater work of the Church’s dialogue with our world.

Clarity before all else; the dialogue demands that what is said should be intelligible. (ES, 81) The caliber of an artist is found not in a work of art standing alone and isolated as if in a vacuum but in the ability of a work of art to engage people where they are at in their lives, to move them and to call forth a response, a dialogue. If there is no engagement, it is fair to question if it is true art. Striving for clarity in dialogue and striving for clarity in preaching matters. Let there be no mistake, this takes work and practice but this ability to translate the realities of faith and gospel into the language of where people are at is extremely important and it marks authentic preaching.

Our dialogue must be accompanied by that meekness which Christ bade us learn from Himself: “Learn of me, for I am meek and humble of heart.” (ES, 81) Our dialogue and our preaching must not be marked by arrogance or bitterness. We must learn the meekness of Christ himself because in this lies the power of the gospel. This “meekness of Christ” sets the words of the Church apart from all the other words that continuously wash over people in their everyday lives. We should not underestimate this characteristic of meekness in the lives of people who are daily inundated and even assaulted by words wrapped in bias, anger, coercion and manipulation.

Our dialogue must have a confidence not just in the power of our own words (which could easily lead to arrogance) but also in the good will of both parties to the dialogue. (ES 81) We must continually seek the good in the other and this must mark the words that we use and the dialogue we engage in. To be a good preacher one must be convinced that people are yearning for the Word of God … and they are. It might not be fully expressed, the desire might even be distorted, hidden or stunted but it is there and the preacher must learn to both listen for that desire and speak to that truth within the heart of people. This is not an easy discipline to acquire in a world that continually seeks to isolate and separate people but it is essential and is truly a counter-cultural witness.

Authentic dialogue must have, the prudence of a teacher who is most careful to make allowances for the psychological and moral circumstances of his hearer … The person who speaks is always at pains to learn the sensitivities of his audience, and if reason demands it, he adapts himself and the manner of his presentation to the susceptibilities and the degree of intelligence of his hearers. (ES, 81)

Prudence is a cardinal virtue and can be practiced and developed by any person. The virtue of prudence is fulfilled in the supernatural virtue of Counsel, one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. Prudence seeks to be aware of the other person(s). The good shepherd knows his sheep. Prudence can be seen as a proactive movement of respect. It is not learning the sensitivities of the other in order to manipulate with the intent of achieving some desired result but learning about the other person in order to meet that person where he or she is at. Authentic preaching must always avoid the temptation to manipulate. I believe that Bl. Paul VI understood this because immediately after this reflection on prudence as a constitutive element of true dialogue he writes,

In a dialogue conducted with this kind of foresight, truth is wedded to charity and understanding to love.

And that is not all. For it becomes obvious in a dialogue that there are various ways of coming to the light of faith and it is possible to make them all converge on the same goal. However divergent these ways may be, they can often serve to complete each other. They encourage us to think on different lines. They force us to go more deeply into the subject of our investigations and to find better ways of expressing ourselves. It will be a slow process of thought, but it will result in the discovery of elements of truth in the opinion of others and make us want to express our teaching with great fairness. It will be set to our credit that we expound our doctrine in such a way that others can respond to it, if they will, and assimilate it gradually. It will make us wise; it will make us teachers. (ES, 82-83)

In the dynamic of manipulation, I try to force you to change, consciously or unconsciously. Authentic dialogue stands opposed to manipulation in all its forms. Authentic dialogue summons both parties to an honest investigation of the subject at hand as well as a fearless rooting out of the tendencies of manipulation that each one of us carry within ourselves.

Finally, the discipline of dialogue and preaching must begin in the witness of the preacher’s own life if it is to be authentic and salvific in the lives of other people.

Since the world cannot be saved from the outside, we must first of all identify ourselves with those whom we would bring the Christian message – like the Word of God who Himself became a man. Next we must forego all privilege and the use of unintelligible language, and adopt the life of ordinary people in all that is human and honorable. Indeed, we must adopt the way of life of the most humble people, if we wish to be listened to and understood. Then, before speaking, we must take great care to listen not only to what men say, but more especially to what they have in their hearts to say. Only then will we understand them and respect them, and even, as far as possible, agree with them.

Furthermore, if we want to be men’s pastors, fathers and teachers, we must also behave as their brothers. Dialogue thrives on friendship, and most especially on service. (ES, 87)

Dialogue and preaching, if it is to be authentic, must become incarnate which means that the preacher’s life must also become incarnate within the life of his community just as the Word of God became incarnate. We are told at different times in the gospel story that Jesus was aware of the thoughts of other people before they ever even expressed them. This was no form of magical clairvoyance on the part of our Lord but the ability to listen to hearts. The Church has been given this ability, the preacher must cultivate this ability. “Heart speaks to heart” noted Bl. John Henry Cardinal Newman. The preacher must learn how to listen to both the heart of God speaking to the heart of his people as well as to the reply and yearning of God’s people.

To end, I would like to share one further quote from Ecclesiam Suam.

To this internal drive of charity (the gifts Christ has bestowed on the Church in abundance) which seeks expression in the external gift of charity, We will apply the word “dialogue.”

The Church must enter into dialogue with the world in which it lives. It has something to say, a message to give, a communication to make. (ES, 64-65)

The preaching task is rooted in the greater task of the Church’s dialogue with the world. As a servant to dialogue, the preacher shares intimately in this task. Hopefully, we can learn from the insight and wisdom of Bl. Pope Paul VI.