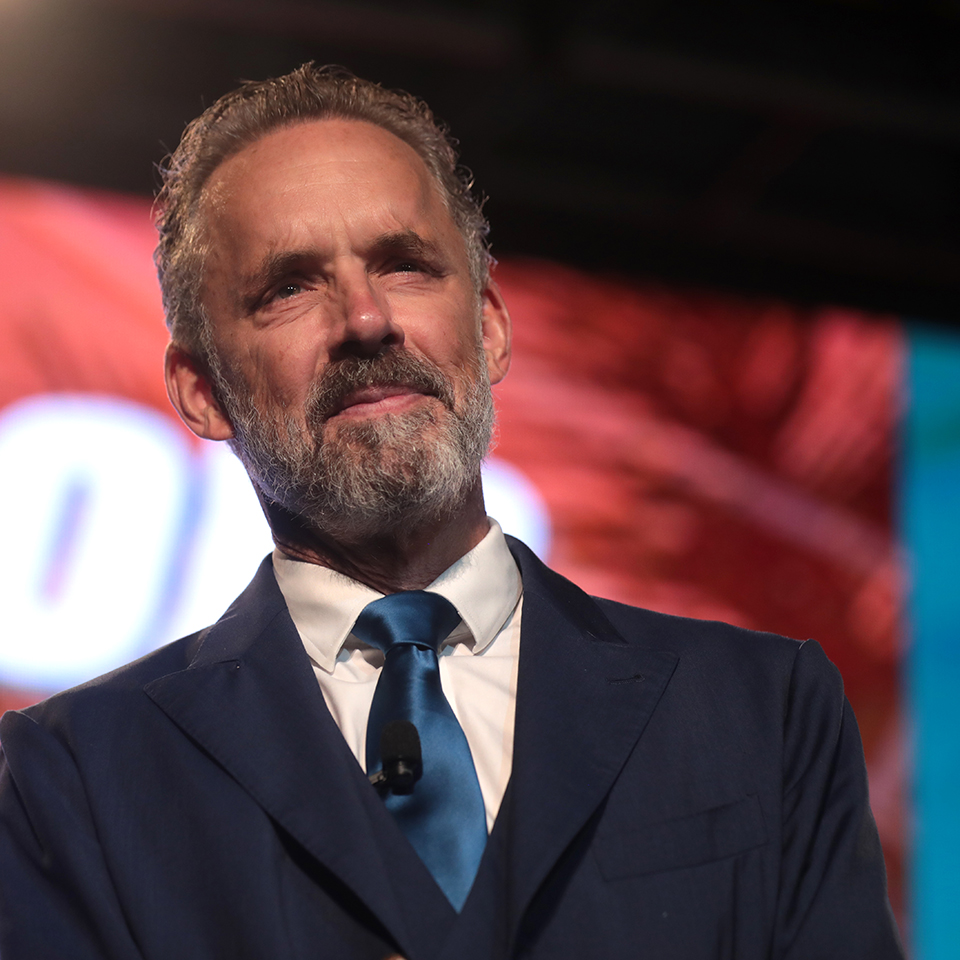

In his must-watch and much-discussed conversation with Jordan Peterson last year, Bishop Barron used a particular word no less than thirteen times: praise.

At one point he explains:

The biblical key is always right praise. I go right back to Genesis 1. When we give praise to God, drawing all creation together, then our soul becomes ordered properly, and then around us a kingdom of right order is built up. In the Catholic Mass we have that wonderful prayer, the Gloria. We say, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will.” It’s like a formula, that if I give glory to God in the highest, then there will be peace around me.

Peterson responded positively (this was like a “condensation of the Sermon on the Mount,” he says). But almost immediately, he maps the idea onto his own psychological horizon, returning to the core ideas that have resonated with so many: aiming at the highest possible values, the amelioration of suffering, the constraint of malevolence.

It’s very interesting that this particular point of “right praise” vs. “bad praise” became so central in their conversation. (One commentator picked up on it right away.) While he has been famously coy on whether he believes in God or identifies as a Christian, Peterson’s ideas have opened up the Bible to countless agnostics and lit up the minds of countless Christians. There is much to commend in them from a religious and specifically Christian standpoint. And indeed, Bishop Barron and Jordan Peterson find lots of common ground both psychologically and biblically. But again and again, the former steers the conversation up to the question of divine praise, and the latter steers it back down to the question of human purpose. The first wants to understand man in light of God, the second God in light of man. Like two trains running on parallel tracks, they see eye-to-eye and look out on much of the same terrain, but never quite converge—and what separates them is the properly religious idea of praise.

I thought of this conversation in light of a recent preoccupation with a very short, profound, and often overlooked Catholic prayer:

Glory be to the Father,

and to the Son,

and to the Holy Spirit.

As it was in the beginning,

is now, and ever shall be,

world without end.

Amen.

Popularly referred to as the “Glory Be,” this prayer is an ancient doxology (from the Greek work doxa, meaning glory or praise) that emerges out of both the Church’s Scripture and Tradition. And though there are slight variations across different languages and cultures, it also spans both “lungs” of the Church—East and West—with versions not only in Latin but also in Greek, Syriac, and Arabic. For Catholics, it is probably most familiar as the prayer that concludes a decade of the rosary. It is also an integral prayer of the Liturgy of the Hours.

But the Glory Be is not just a prayerful punctuation mark or a nice-sounding way to conclude other more important prayers. From the very first word, it is, in a way, the most important prayer there is.

In his famous 2005 commencement speech at Kenyon College, David Foster Wallace said,

There is no such thing as not worshiping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship . . . is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth.

Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. . . . Worship power, you will end up feeling weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to numb you to your own fear. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. . . .

The so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self.

Wallace was onto something. When we glorify wealth, pleasure, power, or honor, making them the center of our lives, we fall apart. When we glorify our nation, politics, or family, using most of our attention and energy to protect them, chaos ensues. Why? Because we are turning the ego into God, or making some other finite reality our ultimate concern. We are engaging in bad praise, and bad praise is what lies behind all the moral and spiritual wreckage of the world. But worshiping whichever god or spiritual thing best suits our own needs and desires—making “religion” or “spirituality” a subtle excuse for more self-worship—certainly won’t pull us from that wreckage.

This is why the prayer begins with “Glory,” but immediately orients our praise, with laser focus, to the only reality that can ultimately give us peace in return: the Father (who created us), the Son (who was sent to redeem us), and the Holy Spirit (who is sanctifying us). While these three names refer to three distinct persons of the Trinity, those three persons are all the same reality: God. This is the one, true God of Israel, fully revealed in Jesus Christ and continuing his work in the world through his Church.

The latter half of the prayer, too, is profound. Peter, referencing Isaiah, observed, “All flesh is like grass and all its glory like the flower of grass. The grass withers, and the flower falls” (1 Pet. 1:24). But God is the Alpha (“as it was in the beginning”) and the Omega (“and ever shall be, world without end”). His glory is not just a construction of the human mind or a projection of human will, but a transcendent, eternal reality beyond all of space and time. And this God “is now”—here and now—bringing you, me, and all of reality into being. There are two other important truths embedded in this: God is not “a being” who somehow needs us—he is forever glorious whether we give him glory or not—and therefore, giving God glory is not a threat to human flourishing; just the contrary. As St. Irenaeus put it: “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.” And human beings, body and soul, are ultimately called to divinization—to become partakers of God’s own nature (2 Pet. 1:3-4)—a transformation completed in the glory of eternal life but beginning here and now in the world (2 Cor. 3:18).

The Glory Be concludes with the familiar but not insignificant “Amen”—a word originating in a Hebrew affirmation of what has just been said. In other words, to say “Amen” is to remind yourself that this is not just psychological or moral truth; it is metaphysical truth.

In the wake of his emotionally charged interview with Bishop Barron, we’ve learned more about Jordan Peterson’s own hidden confrontation with suffering. Indeed, as Bishop Barron recently observed, the coronavirus pandemic is bringing a lot of people face to face with an uncomfortable truth that they very often try to ignore: that the world and everything in it is fragile and fading away. Could religious “nones” suddenly be searching for the meaning of life and the existence of God? Might this even be that “limit experience” that moves them—perhaps for the first time in years, or even the first time in ever—to pray? Perhaps a seeker’s first prayer is just a holy cry from the heart—a pure and honest pleading for help in the face of uncertainty, even unbelief. But for those religious seekers desiring to pray but unsure of what to say or how to say it, the right praise of the Glory Be—short but profound, ancient but ongoing, essential but inexhaustible—might be the perfect mantra.

Peterson once told Sam Harris that his idea of prayer is sitting on the edge of your bed and confessing—“to yourself as much as to anyone”—what you’re doing wrong, and what you could do to make it right. As noble as this may be, there is something qualitatively different about falling to your knees, looking outside of yourself to the God of salvation, and crying out with the Psalmist, “Not to us, Lord, not to us, but to your name give glory” (Ps. 115:1). This is praise. And only right praise can finally make things right.

Photo by Gage Skidmore.