Our Catholic faith is rich. Like a gem, its various facets add to its splendor. Anyone who has followed my work knows that one of my own hobby horses is the unity of the different aspects of our faith as part of one, glorious whole. I often call attention to how the different parts relate to one another, since each part is understood more completely in light of the others. Similarly, a jewel’s beauty is reflected most fully when one beholds the facets altogether.

At the same time, to appreciate the unity of the faith, each facet—while keeping in mind its relation to the whole—needs to be understood. The liturgical calendar provides us with the opportunity—throughout the year—to focus our attention on this or that aspect of our faith so that we can appreciate its particular contribution to our faith’s magnificence.

The season of Lent is a penitential season wherein we focus on our need for redemption, repent of our sins, and humbly accept the gift of salvation won for us by Christ. Lent is also a time to redouble our regular ascetic practices to feel in our bodies the privation of the good that sin brings.

Such acts of self-denial involve the intentional acceptance of suffering. For many of us, fasting is especially difficult. Few of us experience true hunger in our day-to-day lives. When our stomachs cry for food, we happily obliged, quickly abating uncomfortable hunger-pangs. During Lent, especially on days of fast (whether mandated, such as on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, or voluntary on additional days we select for ourselves), we forgo that which we would otherwise have legitimate rights to, accepting the suffering involved as a form of penance for our sins.

The more we sin, the harder it is to stop.

In addition to helping us feel the suffering that represents the just punishments due to sin, fasting is also strengthening. Like our muscles, our wills need to be exercised so that they gain strength. One of the characteristic effects of the Fall and of our personal sins alike is a weakening of our ability to choose to act rightly. The more we sin, the harder it is to stop. The more we choose to sin, the more likely we are to fall when presented with temptation. Fasting acts as a spiritual exercise that helps us gain more control over our passions and desires so that we control them rather than allowing them to control us.

When we fast, we say no to something that, objectively speaking, is not bad. In fact, food—at least healthy food—is good for us. However, by denying ourselves that which we ordinarily would have a legitimate right to, we are strengthened in our ability to deny ourselves those sinful pleasures that we do not have a right to. We exercise our wills via fasting so that we can gain greater self-control. When done regularly, fasting can help us overcome those sins that we tend to fall into time and again.

In addition to fasting, it is wise to employ other practices that focus on building up the virtues. The life of holiness to which we are all called does not consist in merely avoiding sin. Rather, holiness consists in positively acting in a godly manner. It means acting virtuously. Avoiding sin is only a first step. The ultimate goal is to become virtuous and blessed: holy. Therefore, it is important to learn what the virtues are and to intentionally develop the habit of enacting them.

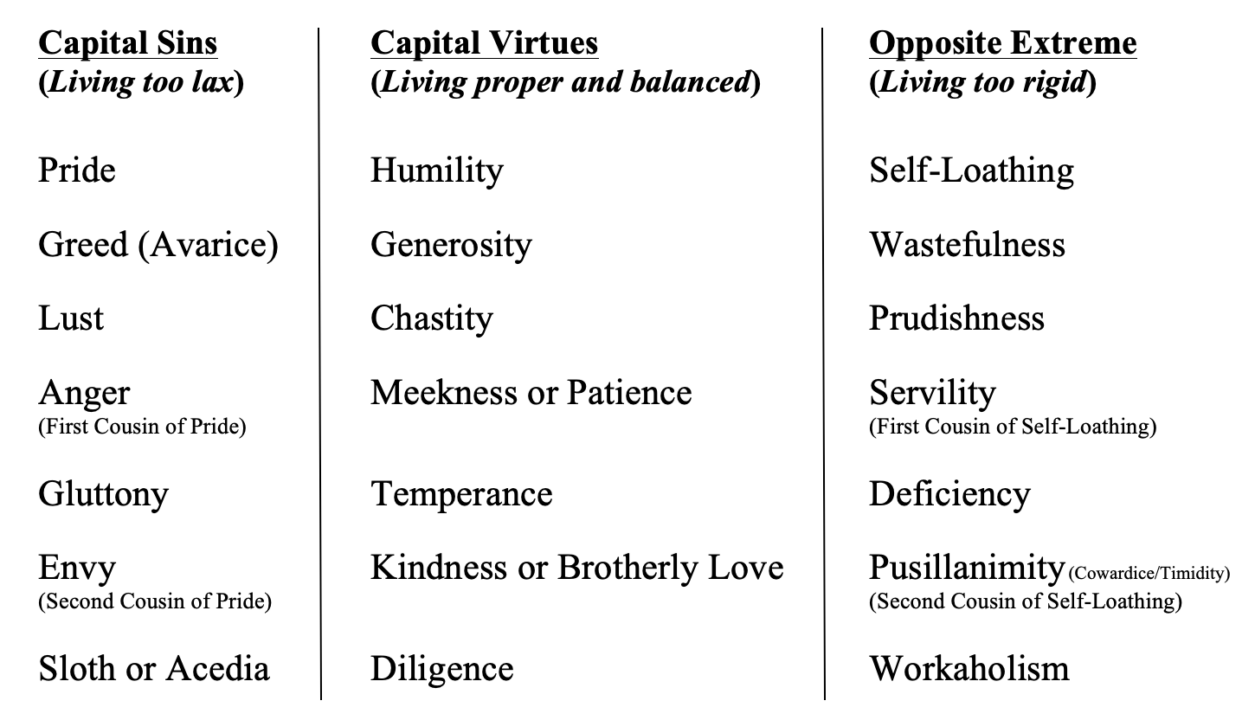

There are different ways of categorizing virtues and vices. Here, we will discuss the Capital Virtues and their corresponding vices. A virtue is the mean between two vicious extremes. We can fail to exercise a virtue either by privation or by excess. The sins of privation are called the Capital Sins. These are the ones most often discussed when speaking of vices, but it is also possible to have the vice in opposite extreme.

For the sake of easy reference, here is a helpful chart from The Fathers of Mercy:

In moral theology, we talk about three general states. First, there is the state of vice, wherein we habitually fall into committing the particular vice in question, whether privational or excessive with respect to the virtue. Second, there is the state of continence, wherein we avoid committing a particular vice, but it is difficult and unpleasant to do so. We choose to do the good, but reluctantly, not enjoying it. Third, there is the state of virtue, wherein we enact the virtue with relative ease and enjoy doing so. The good news is that whether we are in a state of vice or continence, over time, we can become virtuous. That means we can actually enjoy living the virtues. That is why it is called blessedness or happiness. When we are virtuous, there is a deep sense of peace and delight that comes from doing the good. That’s our goal.

Hence, during this season of Lent, it is a particularly fitting time for us to take stock of which stage we are currently in with respect to the virtues and the opposing vices. We can then begin to intentionally counteract the vices we personally struggle with the most so that we can move towards the virtue.

The reason fasting is so beneficial is that it helps strengthen our will power so that it becomes easier and easier to reject temptations and embrace virtues. Fasting is most effective, of course, when it is preceded and accompanied by a sound life of prayer. The truth is, we cannot simply overcome our sinfulness without God’s healing grace. Being united to God through prayer opens us up to receive the graces God offers us, making the process of moving from vice to continence into virtue much easier and smoother (or, really, possible at all).

Prayer and fasting, then, are indispensable means of becoming the saints we are called to be. So, rather than fasting and making other sacrifices begrudgingly out of a sense of obligation, let us approach this season of Lent for the gracious opportunity it truly is. For, by means of these lenten practices, we work towards a greater state of happiness (blessedness). We may find it difficult for a time, but the better we live out this season of Lent, the more able we will be to enjoy the gift of new life made possible by the Resurrection, which we will celebrate at Easter.