In Matthew’s Gospel, we hear that “Jesus told the crowds all these things in parables; without a parable he told them nothing” (Matt. 13:34). St. Mark tells us that Jesus “began to teach them many things in parables” (Mark 4:2) and that Jesus told the disciples, “To you has been given the secret of the kingdom of God, but for those outside, everything comes in parables” (4:11). The parables themselves are so famous and familiar that some of them, like the “good Samaritan,” have even made their way into common usage, detached from their original context. In fact, the very idea of a parable as part of our Lord’s teaching is so familiar that we may overlook them, but I would venture to suggest that we could learn some important lessons about evangelization from the nature of a parable.

The Old English term for this literary device was bispell, a compound of “by” and “tale or discourse.” The specific word “parable” arrived in English around the thirteenth century, coming from French via the Latin parabola (comparison), which in turn came from the Greek parabolē, whose component parts literally mean “placing side by side.” In the development of language, the Latin parabola came simply to mean “word,” developing into modern forms such as the French parler (to speak).

What this etymological excursion tells us is that the word parable has, at its heart, the fundamental issue of communication. It is purposeful, not decorative, and its function is to express a moral or spiritual truth by means of a realistic story.

Some parables are fairly straightforward, yet others are difficult to understand, and we find in Scripture that this is intentional. Jesus even said straight-out, “The reason I speak to them in parables is that ‘seeing they do not perceive, and hearing they do not listen, nor do they understand.’” (Matt. 13:13; see also Luke 8:9-10). This latter approach seems counterintuitive. If he knows that the crowd won’t understand, why does he not speak plainly?

Let’s take a closer look at the disciples’ reaction in Luke’s version. Jesus tells the parable of the sower, and declares, “Let anyone with ears to hear listen!” (Luke 8:8). What happens next? The disciples “asked him what this parable meant” (8:9) and our Lord responds by giving a detailed explanation of its meaning. I think we can draw the conclusion here that his audience was not just the Twelve, but a much larger group of disciples, for he continues teaching with several more parables until his mother and other relatives attempt to see him but are unable to get through because of the crowd (Luke 8:16-21).

The master teacher has intrigued his audience, and he has also given them the opportunity to exercise initiative—to ask him about the meaning of the parable. Following Christ is a total commitment; it’s not just something you know about but something you do. But if we’ve gotten into the habit of being passive, letting others tell us what we need to know, unfamiliar with even the slightest moral exertion, then we need to get some mental and moral exercise.

Presented with a puzzling parable, Jesus’ audience had the opportunity to take some small steps on the way—for some of them, perhaps their first, tentative steps—by asking, “What does this mean?” And by asking the question, they took ownership of it, and they were thereby more ready to truly hear it, reflect on it, and be changed by it.

We can, then, learn an important lesson about evangelization from our Lord’s parable. It is important not just to allow but to encourage or even require that our audience take part in the conversation. As an experienced teacher, I know first-hand that it simply doesn’t work to just tell students what you want them to know, nor just to assign readings and hope for the best. Students need to be interested in what you’re saying before they will pay any attention, let alone make an effort to understand. They need to be motivated, to be involved—in short, to have some stake in learning what you are offering to teach. The motivation might be the purely utilitarian one of getting a good grade on the test, but that’s a start! When we are evangelizing, the motive our audience has for listening to us might not be particularly noble; it might be mere curiosity or even the desire to prove us wrong.

Unfortunately, not everyone who hears will be interested in asking those questions and learning more. Even when Jesus himself was preaching, not all of the crowd stayed to hear the meaning of the parable; it must have been saddening to see the group thin out as people walked away, uninterested in hearing the meaning of the parable. Of the ones who didn’t stick around, very likely some of them were dismissive and spread disparaging reports: “We went to see this so-called preacher, and all he did was tell stories about seeds. That’s not what I want from a sermon!” This is a function of our free will, and of the way that we learn and grow. Conversion and spiritual growth do not happen to us without our cooperation.

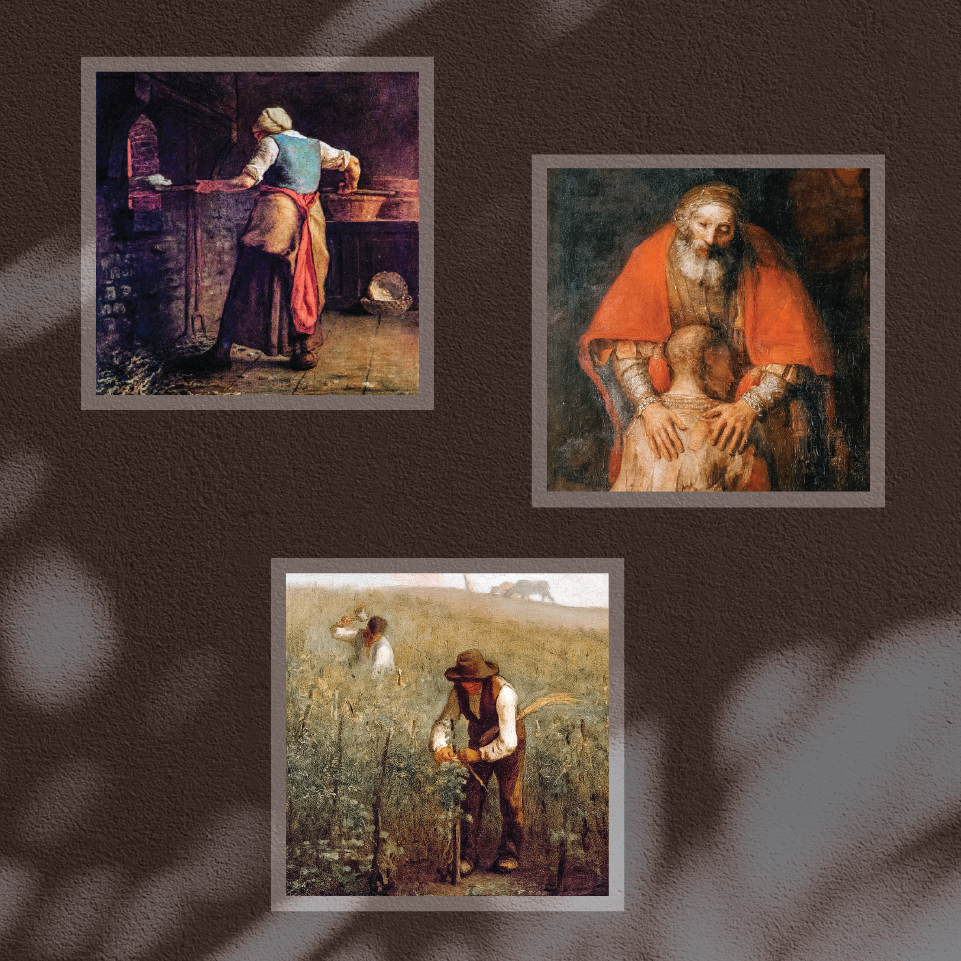

The form of the parable, then, helps to remind us of both the limits and the requirements of our work as evangelists. We can never make someone engage with the truth—but we should also never assume that walking away from any one interaction is the end of the story. The parable of the two sons is a helpful reminder: one son said “I will not” when his father asked him to work in the vineyard, yet he later changed his mind and went to work (Matt. 21:28-31). We must be patient; some of those who seem to pay no attention right now may in fact be reflecting on what they have heard, and they may be truly changed by it.

These lessons about evangelization are illustrated in another parable: “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened” (Matt. 13:33). Various ingredients are needed to make bread: yeast, to be sure, but also flour, water, and salt. The baker mixes the yeast into the flour, kneads, and waits. Time is required for the yeast to do its leavening work. Indeed, at first, the dough will look disappointing, a fraction of the height of the desired loaf. The dough must be set aside in a warm place, covered, and given time to rise undisturbed. Then—if all is well—the yeast will do its secret work and produce a lofty loaf.

To be sure, sometimes the yeast has become stale and ineffective, or there’s too much salt in the dough and the yeast is stunted, or the temperature is too cold to allow it to rise, or it’s disturbed while it’s rising and the dough collapses, or it’s left too long and is “over-proved” and falls while baking. A wise baker does not blame the bread for not rising, but rather investigates what has gone wrong and makes adjustments in technique and in the recipe as needed, and recognizes the role of outside factors. If all I have on hand is all-purpose flour, my loaves will inevitably be lower and less impressive than if I could use high-gluten bread flour, but this is no reason to despair. Rather, I’ll attend to the other factors and endeavor to make the most nourishing (albeit low-profile) loaf that I can with what I have available.

Just as yeast does not instantly make nourishing bread by itself, truth does not transform lives unless and until it is activated, given form and substance, and allowed time to develop. As we can see from these parables, to evangelize well, we need the proper ingredients—but also practice, prayer, and patience.