I don’t love poetry. But I’m trying to change that.

On most days I (like you, perhaps) find the prospect of reading poetry rather unappealing, especially considering the other options on the bookshelf. Here’s how it usually goes: There is limited time in a day for reading and unlimited good books to be read; and, what is more, I often find poetry to be intolerably weird not to mention unsatisfying because I can’t understand a lick of it—or at least not enough of it to have a lasting impact. And a relativistic “make it mean what you want” approach is about as satisfying as going to the local park and telling yourself it’s Disneyland. No—I want real, mind-to-mind contact. I want to know what the poets were trying to say to their hearer (of course, at least in some cases, whether they themselves knew is another question).

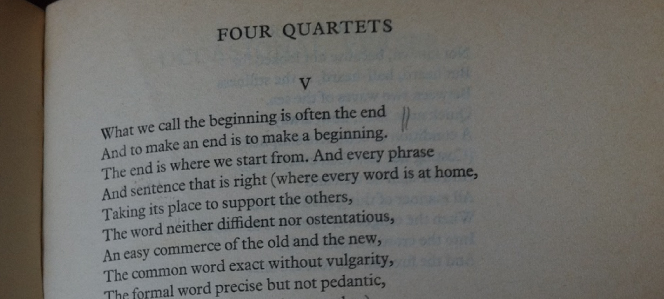

But choosing to read, say, T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” instead of something by Plato or Cicero or St. Thomas Aquinas or Pope Benedict XVI or Bishop Barron or Josef Pieper or Ed Feser or Jane Austen or Ernest Hemingway or G.K. Chesterton or Michael O’Brien, is like choosing fried grasshoppers and a glass of lukewarm milk over a burger, fries, and cold pint of Guinness. It is just not very likely to happen.

Poetry Pains

Now, it is one thing to actually make the initial choice to forgo prose for poetry, to reach past Peter Kreeft to George Herbert. That process itself requires a great interior war to be waged, and a valiant victory of will to be won (again, I am speaking for myself and other prose-inclined folk).

But then comes another battle. Which battle exactly? Let me illustrate. Imagine you are going to try to give Eliot’s “The Waste Land” a stab (you have, after all, heard that it is one of the most important poems of the twentieth century).

You read the first stanza:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

“Okay,” you say to yourself, pondering again on the first line, nodding your head with a spark of confidence, “I can work with this. April is pretty cruel indeed—not only because it bears the unpredictable and sometimes harsh transition from winter to spring, but also because it is a pitiless tease, bringing warm breezes and sunshine on one day and a blizzard on the next.”

You re-read the next few lines (perhaps with pipe in mouth) pondering on the lilacs, the dull roots, the spring rain; and you exclaim to yourself after reading those lines, “This is good stuff, T.S—what splendid imagery! Thank you for speaking my language! I can totally see why this poem is a classic!” With great excitement, heart rate intensifying, you continue reading and pondering; and after three more lines of splendid springtime imagery you read this:

Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

Your heart sinks. Your pipe goes out. Dejected at another failed attempt to read the poetic musings of a proclaimed genius, you close your poetry anthology—and go back to Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules For Life: an Antidote to Chaos.

This has been my experience countless times in the past. I overcome my nagging desire for prose and, in a heroic moment, grab a poetry book off the shelf; but within thirty seconds my mind has wandered afar, and I find myself completely unmoved—and completely unengaged with the poet. So I close the book and go back to the bookshelf.

All that being said, my experience with poetry has not been entirely negative. Not by a long shot.

Imitating the Greats

I am learning to like poetry. But why bother, you might wonder?

“Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ,” wrote St. Paul (1 Cor. 11:1). Following a less perfect but perfectly sensible way we might also strive to imitate great men. Indeed, both of these summons to imitation have become key guiding precepts of my life.

One way we can discern how to imitate great men and women is by asking, simply: What did they do? A second question, a deeper question, might then follow: What did they like? Whereas the first question examines the exterior life, the second looks deeper into their interior life.

A couple years ago I started listening to classical music—Palestrina, Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Haydn, and others—because it was constantly coming to my attention that many commendable figures, Catholic and not, had a great affection for them. “If great men have had such an affinity for the music of Beethoven,” I thought to myself, “then I ought to try like Beethoven too.” I knew there must be something profound—something objectively real and beautiful—waiting to be discovered in, for instance, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto or his 9th Symphony. I was right. And the project continues—as it does with poetry.

It has also become clear to me that many of the great men and women of the past have also cherished poetry. From King David to St. Paul, from St. Thomas Aquinas to St. Thérèse of Lisieux, from Cardinal Newman to Pope John Paul II, poetry has held an important place in the lives of even the greatest men and women to have ever lived. Most of these, in fact, were not only hearers but doers—makers—of poetic verse. But why? What is it about poetry that makes it so beloved, even among the saints?

Expressing the Inexpressible

“Seeing one of my sisters paint charming pictures and compose verses,” wrote St. Thérèse, “I thought how happy I should be if I could paint also, could express my thoughts in verse, and could do much good to others.” The question is this: Why should St. Therese—or anyone else for that matter—desire to express their thoughts in the form of poetry?

The nature of poetry gives us a hint at the answer. G.K. Chesterton says in his essay “How to Read Poetry” that the key to understanding poetry’s inner essence is to understand that it is exclamatory. “Our feelings, even about small things, when these feelings are sufficiently intense, demand a haughty and heroic language, and, sometimes, a supernatural language,” he writes. American poet Robert Frost put it this way: “A complete poem is one where an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found its words.” Poetry can go where prose cannot—for it possesses the unique ability to express the inexpressible.

It seems, then, that when we feel something deeply—and so deeply, in fact, that we need to express those feelings in human language—poetry is the natural result. Think about when we speak to our lover or pray to God or play sports. The more our emotions are intensified, the more poetic (or metaphorical) our language becomes.

Poetry is the language of the heart. Maybe this is why music (which is really only poetry sung and, therefore, a kind of heightened poetry) often has the mysterious ability to move us more deeply and automatically than any other form of artistic expression. Poetry has a peculiar effect on the human soul. Indeed, as poet Wallace Stevens affirms, “The purpose of poetry is to contribute to man’s happiness.” Children express this truth when they want us to recite their favorite nursery rhymes—again and again and again.

If poetry is our most natural expression of the heart (at least linguistically speaking) then that would explain why it is also among the most primitive forms of art. Chesterton reflects: “The greater part of humanity in all ages and countries would know much better what was really meant by a song than what was really meant by a leading article, for poetry is not an artificial or ingenious or highly civilized thing; it is older than every other literary form.”

Almost every civilization before ours used poetry—not prose—to express almost anything worth expressing. Chesterton muses on this further: “Moderns put their poetry into poems, and the rude and ancient peoples put their history and politics, and sporting news, and advice to gardeners, into poems.”

Whatever poetry is, it is ever ancient and ever new. It is a necessary product of the God-like faculties of the human person. We all ought to learn to like poetry, for it is the closest we can get to speaking the deepest truths about reality.

Moving Forward

I have discovered poetry to be worth the struggle and I hope you find the same to be true. As poet Dana Gioia has remarked, “In a better world, poetry would need no justification beyond the sheer splendor of its own existence.” We live in the least poetic society in human history: we should not be surprised at our difficulties. But we should not be content with them either.

I have also learned that some poems are better read by beginners than others. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” is a great choice—at least once you have adequately considered the technical subtleties, historical nuances, and literary allusions within. I do not recommend beginning with “The Wasteland,” in other words.

Where should beginners start? Well, that’s a question for another article. Stay tuned, friends.