In Paul’s First Letter to Timothy, we read, “Beloved, let no one have contempt for your youth, but set an example for those who believe, in speech, conduct, love, faith, and purity. . . Do not neglect the gift you have” (1 Tim. 4:12, 14).

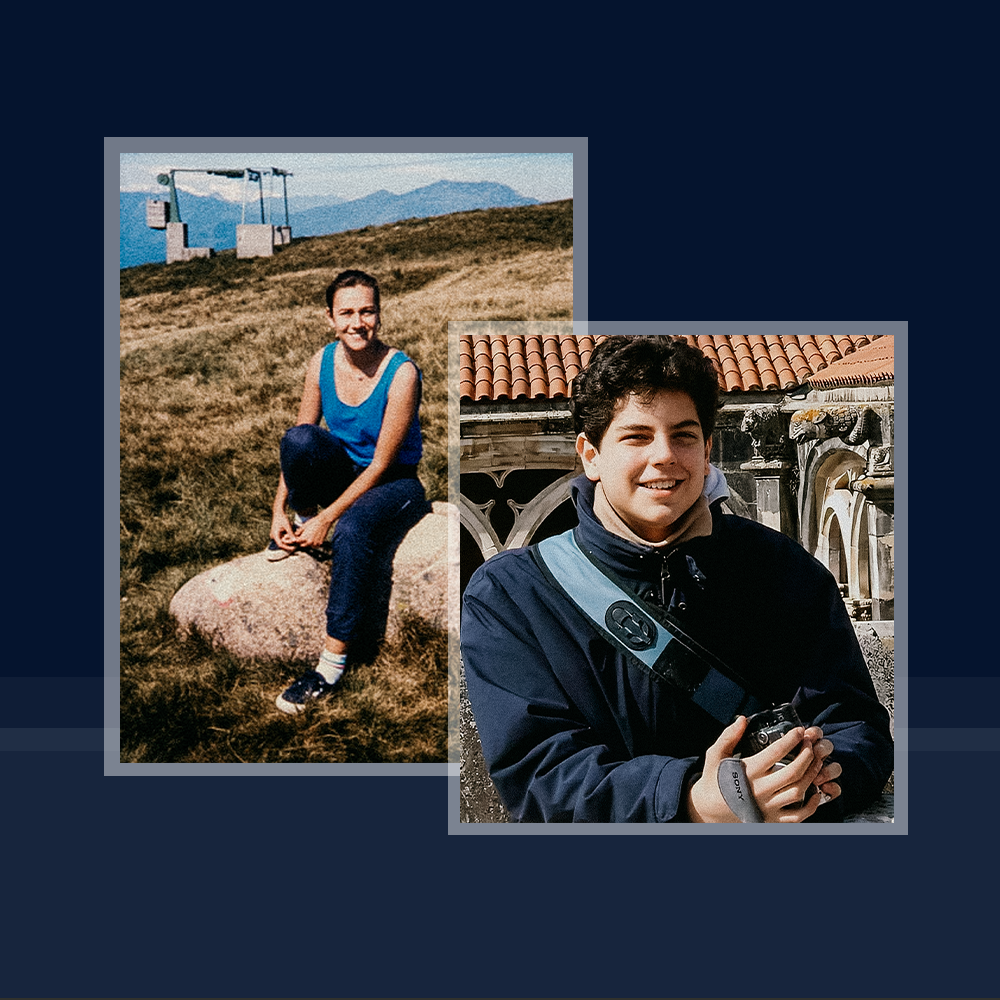

It’s good advice for all of us, no matter what our age—most particularly, the adjuration not to neglect the gifts we have been given, however it may manifest: to preach, heal, cook, train, write, etc. Our gifts were never meant for ourselves alone, but for service to the Body of Christ, no matter what our ages. What has been gifted to us in youth may need to be seasoned, yes, but never ignored or put aside or outright stalled, because—as in the lives of Blessed Carlo Acutis and Blessed Chiara Badano amply demonstrate—our years are fleeting, and we may never be given enough time to come into the world’s estimation of readiness.

A few years ago, I had the good fortune to enjoy a terrific meal in Rome with a number of Catholic journalists from different countries. At some point I betrayed the weird sort of situational ingenuousness that has (at times) convinced others that I am naïve in matters of faith. I am not naïve, but I will say my faith is artless and often can seem simplistic. I just figure if I believe what I believe, there’s no need to complicate it, even though I know that, sometimes, it can make me sound almost childish. In any case, whatever I had said caused one dinner companion to give me a stunned look. “You are so strange,” she said, but I could almost see her mental rolodex flipping through synonyms, looking for the English word she really wanted. She struggled with it for a while and then shrugged. The best she could come up with was “unguarded.”

Well, I was willing to accept that. “I suppose you’re right,” I admitted. “It’s probably why you Europeans all confound me, and I you. Your social parlay is a game ripe with history and intrigue, and you think mine is too, until you realize I haven’t a clue how to play, and am not far removed from a slack-jawed yokel.”

“Without guile!” she declared.

“Sure, like Nathanael,” I shrugged. “Good enough for Jesus, so I’ll do for the table here, yes?”

Thankfully, she laughed. But that wasn’t the first time I’d been made aware of the fact that I am generally unsophisticated. Cynical, skeptical, and sometimes sour I can certainly be, but not sophisticated.

I’m okay with that. In fact, the more I see of the “sophisticated” world—whether through images of politicians and celebrities partying, all unmasked while their servers and paid underlings faces are conspicuously covered, or my own amused experience of being literally sniffed at by a woman in full equestrian gear while we both shopped for a high-end gin—the happier I am to be a bit of a plodder. It gives me hope that, sarcastic as I may be at times, I still have something of the child within me, which is no bad thing. In fact, it may be an essential part of staying alive “in joyful hope” when life is making you feel not youth but almost weary unto death, as it does sometimes.

We generally take “childlike” to mean humble, or obedient, or trusting. But children can also be cunning little liars or swaggering bosses of the family.

Not quite what Jesus had in mind, perhaps, when he said, “Unless you become like children, you will never enter the Kingdom of Heaven” (Matt. 18:3).

What qualities of youth might both please God and reveal his workings to us? A child is a vulnerable thing. She needs to be fed and sheltered, and she relies upon the parent to sustain her life.

He comes to his parent with even simple needs.

She takes the world at face value: Rain is not wind. Scary is not nice. Cookies are good. There are no euphemisms in a child’s world.

She has many questions, though, and will keep asking until a reasonable answer comes.

He loves and needs to feel loved in return, or he will literally wither and die both in body and spirit.

A child also—and frequently—will loudly demand, or tattle on others, or mindlessly babble nonsense and make more noise than is ever necessary.

As we mature out of youth and become self-sufficient, we suppose we have sufficient wisdom and wherewithal to handle everything—answer all the questions, provide for ourselves. We will not consent to dependency. The idea of vulnerability becomes anathema: “What kind of ‘winning’ is that?”

The saints, though—from Teresa of Avila, to Thérèse of Lisieux, to Teresa of Kolkata, and all of the holy men and women who came before and after young Carlo and young Chiara—demonstrate a common willingness to depend upon God for everything. They consented to being open to the world and to love, and they were ready to be loved in return, with the comprehensive but not-always-comprehensible love of God.

They were childlike in their dependency, trusting in surrender, and they did not babble nonsense. They were not mindless with their words; they did not adopt rowdy-group mentalities or make noisy comparisons between themselves and others. They did not engage in the sort of mundane squabbling or glad-handing that fills our days, especially if we spend any time online. They did not consent to self-censorship, except, perhaps, in order not to wound charity, which would redound to their own souls.

God wants our vulnerability and dependence; he wants us to love, and to be open to his love in return. He delights in our questions, because they show we’re paying attention.

All that other noise? Not so much.