NOTE: This review contains spoilers.

If you enjoy the fiction of Flannery O’Connor, then you’ll enjoy Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, the latest film by Martin McDonagh. In fact, O’Connor’s most famous story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” makes an appearance about five minutes into the film as Red Welby (Caleb Landry Jones) is reading it when Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) storms into his office with a big wad of cash, asking to rent three billboards on an old country road just outside of town.

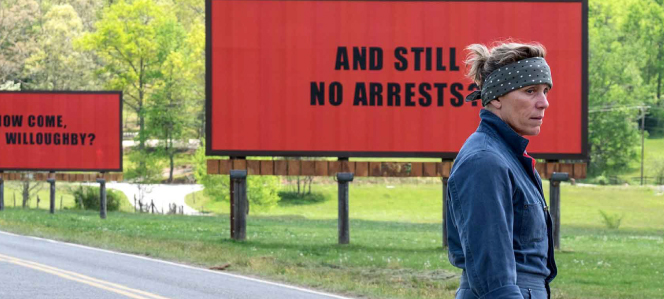

It’s been seven months since Mildred Hayes’ teenage daughter was raped, set on fire, and murdered, and upset that the local police have not found her killer, Mildred takes justice into her own hands. Her plan is to get the attention of the local police department, specifically Chief Bill Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), and force them into action with three billboards displaying the following message: “RAPED WHILE DYING/ AND STILL NO ARRESTS/ HOW COME, CHIEF WILLOUGHBY?” Mildred is a grieving, angry mother, but she’s not the only one grieving. We soon learn that Chief Willoughby is dying of cancer, but this news does nothing to temper her wrath. Mildred Hayes reminds me of the persistent widow from the Luke’s Gospel (18:1-18) in her tenacity; she’s most determined to fight for justice no matter the cost.

The first display of empathy we see from Mildred comes in the interrogation room at the Ebbing Police Station. Mildred is brought in for assaulting her dentist, who was not a supporter of her billboard campaign, and she and Willoughby are in the middle of a heated argument over the billboards when suddenly, in one violent cough, Willoughby sprays blood all over her face. Mildred immediately gets up from her chair and embraces Willoughby and calls him, “My baby.” There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that this scene was inspired by McDonagh’s reading of “A Good Man Is Hard To Find,” specifically the scene where the Grandmother reaches out to the Misfit while saying, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children.” In both narratives it’s a moment of grace when ‘the other’ is recognized as a fellow human being and not merely a competitor. In Three Billboards it’s our first indication that there is something beyond grief and anger for Mildred and for all who are grieving.

One of the best things about Three Billboards is that you really never know who to root for as you’re watching it. Every major character has a major flaw, but redemption is always close at hand, and sometimes it is found, albeit in very strange and often violent way, keeping with the spirit of Flannery O’Connor. Fire, in particular, plays an important role in this film, as it shows up three times. Its power is not limited to destruction but also allows for purgation, purification, and healing.

The names of McDonagh’s characters in Three Billboards are very clever and seem most deliberate. Jerome (Darrell Britt-Gibson) is the name of the guy who works for the billboard company and applies Mildred’s word-only message to the billboard frames. St. Jerome is the patron saint of Scripture, i.e., The Word, so it’s hard to believe there’s coincidence here. Jason Dixon (Sam Rockwell) is a racist, whose name appropriately alludes to the Mason Dixon line; he’s also a mama’s boy and an Ebbing police officer.

Penelope (Samara Weaving), the girlfriend of Mildred’s ex-husband and apparent cause of their divorce, is the complete antithesis of Penelope from Homer’s Odyssey. And Chief Abercrombie, who is an African-American, the only one on the Ebbing police force, shares his name with Abercrombie & Fitch, a preppy American clothing company that has been sued over the years for discriminatory hiring practices.

If grief is the major theme of Three Billboards, then the desire to get beyond that grief and find healing is always lurking. In some ways I think the billboards themselves symbolize the three crosses of Calvary, as one will often see three wooden crosses on the side of a highway, calling Christ’s sacrifice to mind. The billboards in this film are all old and made of wood, and Mildred visits them often, as one might visit the grave of a loved one. Some of her most reflective and lucid moments happen in the shadow of these billboards. Mildred also places three potted flower planters underneath each billboard and tends to them regularly with care. It’s as if Mildred instinctively knows that life comes after death—we discover that she is a Catholic earlier in the film—but she longs to experience that rising for herself.

How does one get beyond grief and anger? The answer pours forth from the mouth of James (Peter Dinklage), a.k.a. “the town midget,” as he holds the ladder for Mildred while she works on her billboards. He confesses, “I like holding ladders. It’s gets me out of myself.” Sin, anger, and fear keep us locked up in ourselves. The remedy for sin is to give one’s self away in love. Just as Christ poured himself out on the cross of Calvary to free us from sin, so do we find our freedom in receiving his love and making ourselves a gift for others. The scenes of self-giving in this film are surprising, beautiful, and convincing. The only way to real healing is to get outside of yourself.

The final scene of Three Billboards is very reminiscent of the final scene in Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard To Find.” Recall that O’Connor’s Misfit spent most of his life killing people. He thought that if Jesus wasn’t who he said he was then there wasn’t any real pleasure in life but meanness. By the end of the story, after he shoots The Grandmother, The Misfit reconsiders his position. He wonders if there is more to life than meanness and killing people. He admits in the very last line of the story, “It’s no real pleasure in life.” Three Billboards ends on a similar note. Two characters, who throughout most of the film acted out of anger and violence, aren’t so sure anymore if they want to keep on doing what they’ve been doing. They’ve got a long car ride to figure it out.

If you enjoy the stories of Flannery O’Connor and the Coen Brothers films (e.g., Fargo, No Country for Old Men, and True Grit) then you’ll like Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards. There’s a lot of cussing as well as a scathing scene about the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church, so sensitive viewers ought to beware. However, if you’ve experienced deep grief, you’ll understand this film and I think it will bring you some comfort. That was my experience anyway, as well as the experience of Catholic friends who watched it with me over Thanksgiving weekend.