One of the benefits of being a father of ten is that I keep my spirit childlike by pre-screening and consuming lots of kids’ content. The downside is that I have experienced firsthand the woke revolution in kids’ content, which often manifests in the cannibalization and deconstruction of legacy properties. Disney’s live-action remake of Snow White is only the most recent example.

In the original Grimm fairy tale, which the classic film largely adhered to, “Snow White” is so named because her skin was “white as snow” and she finds refuge with seven dwarves. But, in the world dreamed up by woke identity politics, whiteness is inextricably intertwined with oppressive power structures and therefore is an ineradicable human stain akin to original sin, but without the hope of baptism. Hence, the new Snow White can’t be white. Instead, she is played by an olive-skinned actress of Colombian descent, and the seven dwarves have been replaced by seven “magical creatures” all sorts of sizes, races, and genders. In the actress’s words, the new Snow White will bring a “modern edge,” in which Snow White dreams not of true love or Prince Charming, but instead of empowerment.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with a story about an olive-skinned maiden who teams up with seven diverse “magical creatures,” to defeat an evil queen and become a girl boss. It just isn’t Snow White. The fact that woke Disney has lost $800 million in a run of eight studio releases, and continues to bleed Disney+ subscribers, suggests that many parents aren’t interested in their children being force-fed the nostrums of identity politics. Increasingly, audiences are looking elsewhere for kid content that is not hostile toward traditional family values.

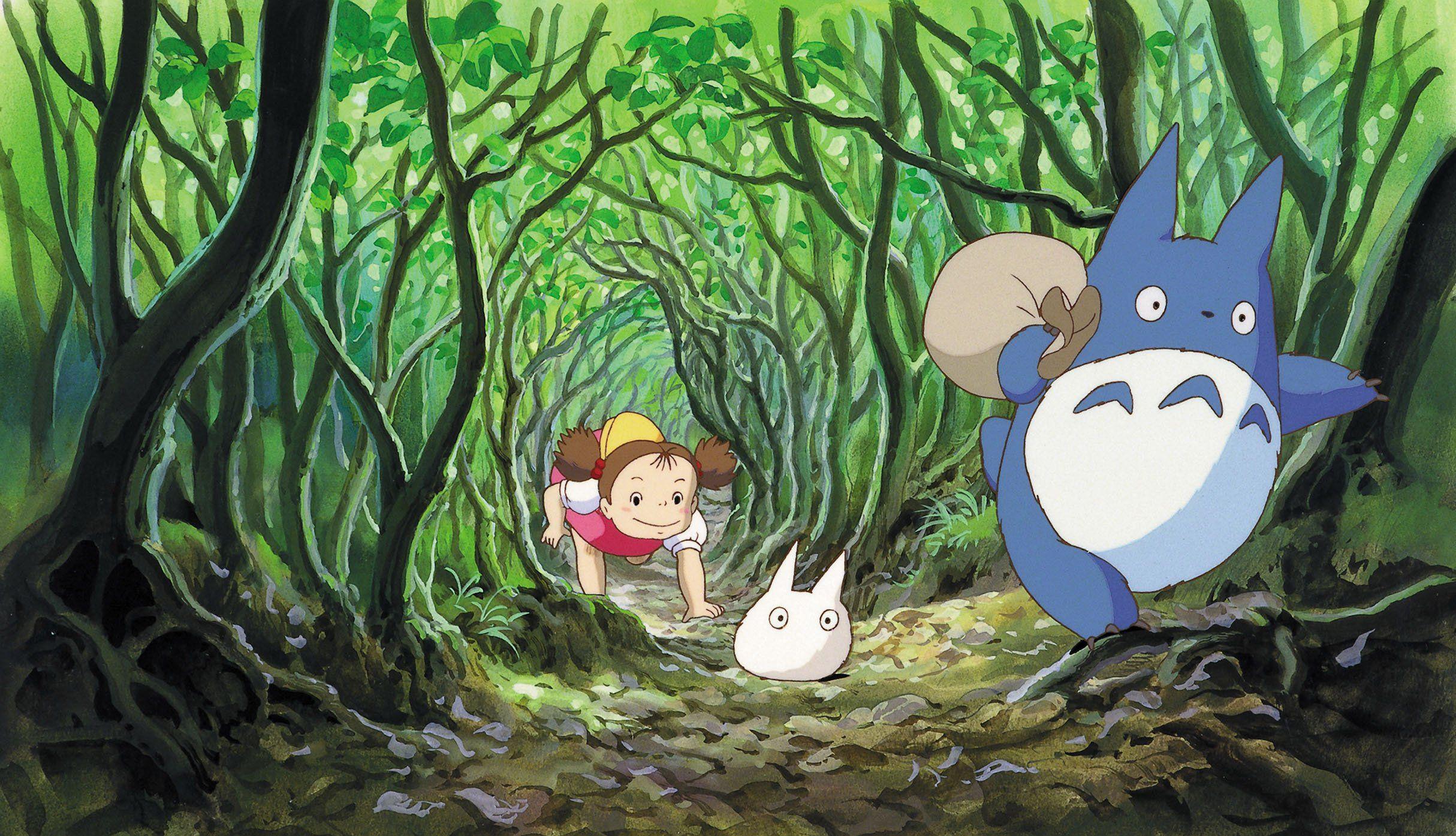

One place parents should look is Studio Ghibli, particularly the oeuvre of Hiyao Miyazaki, whose final film debuts in Toronto soon. Miyazaki’s oeuvre is a delightful collection of beautifully animated stories in which the routine and the mundane of familial and communal life is positively portrayed and intertwined with the magical and the whimsical. As I was considering which films to discuss, I polled my children as to their favorites. It was a three-way tie: My Neighbor Totoro, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and From Up on Poppy Hill. The Cooper family favorites illustrate many of the themes common to Miyazaki’s films, including the goodness of family, tradition, religion, and humane explorations of femininity and masculinity.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

My Neighbor Totoro (1988) features Tatsuo and his two young daughters, Satsuki and Mei, settling into a new home in the country while their mom convalesces at a city hospital from an illness. Told largely from the perspective of the young girls, the trials and sorrows, beauties and joys of mundane home life are the warp and woof of My Neighbor Totoro. Tatsuo is a competent and loving father who is honored and loved by his girls, but their home is evidently incomplete without their mother, and the incongruity of her absence drives the plot. The goodness of the traditional family is assumed as a matter of course.

Miyazaki’s heroines are strong women, without wokeness.

From Up on Poppy HiLl (2011)

Like many of Miyazaki’s films, Totoro is a fairy tale. From Up on Poppy Hill has a more realist-historical bent. Set in Yokohama, Japan in 1963, it is a time of building anew and rapid progress, as the country prepares for its international debut as a new democracy in the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. The post-World War II setting frames the story of 16-year-old Umi and her blossoming romance with fellow high school student, Shun, with whom, she discovers, she has a shared past connected to her father, who died in the Korean War.

Tradition—and how we reckon with it—is the central theme of From Up on Poppy Hill. “It seems the whole country is ready to get rid of the old, and make way for the new,” Umi says, “but some of us aren’t so ready to let go of the past. And sometimes the past is not ready to let go of us, either.” The totem of tradition is an old building on the high school campus that serves as a headquarters for the school’s clubs. It is characterized by dust, cobwebs, burnt-out lightbulbs, and other markers of ruin. And yet, like a living tradition, the building pulsates with life as the teenagers bustle about its innards.

The students have a debate about whether to fight for the building’s preservation in the face of a plan to demolish it. Shun gives a rousing speech in its defense: “You cannot move into the future without knowing the past; destroy everything old and you dishonor those who lived and died before us.” Edmund Burke could not have said it better. Institutions, from school clubs to national legislatures, like the families and groups of persons that constitute them, are partnerships between the dead, the living, and the unborn.

Miyazaki’s heroines are strong women, without wokeness. Umi finds meaning and purpose in daily cooking, cleaning, and care for the boarders who live in her house. With her mom away in America, Umi joyfully embraced various maternal functions in the household. The home is not a shackle on her freedom. Rather, carrying out her domestic duties is the condition of her flourishing and the occasion of her discovery of her true love. Yet, Miyazaki’s heroines also exercise virtue outside the home.

Nausicaä OF THE VALLEY OF THE WIND (1984)

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) is a story of a post-apocalyptic world infected with a poisonous and parasitic forest populated by massive and deadly insects, including the Ohm. Princess Nausicaä’s village, the Valley of the Wind, is seemingly protected from the forest’s poison. The joyous report of the birth of a new child underscores the semblance of normalcy the community has achieved. As an accomplished explorer, flyer, mechanic, and gardener, Nausicaä leaves home in order to place her competence, strength, and determination in service of the Valley. Her principal nemesis, Princess Kushana, is a shrewd political leader who is determined to recover man’s mastery and domination of nature through an ancient technology and burn down the forest, killing the Ohm once and for all.

Nausicaä discovers that this plan will only hasten mankind’s destruction and instead seeks to live in harmony with Nature (symbolized by the forest and the Ohm), even to the point of offering her own life to save her people. Nausicaä, the Princess of Peace, embraces compassion, care, and self-sacrifice in contrast with Kushana’s violence, aggression, and self-assertion, underscoring how heroine strength need not deconstruct femininity, masculinity, and the family.

Through the lens primarily of Shintoism and animistic paganism, religion is generally portrayed positively in Miyazaki’s films. Paradoxically, Miyazaki is clearly enamored of technological progress. And yet technological mastery and its materialistic assumptions comes with the costs of poisoning the environment and throwing man into conflict with nature and the gods. While My Neighbor Totoro offers a positive portrayal of living in accord with gods and nature, Nausicaä (like the later Princess Mononoke) explores the darkness and destruction that ensue when nature or the gods have their revenge upon technological man.

Porco Rosso (1992)

I didn’t mention that I also got a vote. My favorite happens to be the most underrated Miyazaki film: Porco Rosso. No one else voted for it. Good thing my vote counts double.

An Italian ace fighter pilot, scarred by the Great War and apparently cursed as an anthropomorphic pig, Porco leads an epicurean life. He lives on a secluded Mediterranean island, red seaplane docked nearby, and spends his days sunbathing and sipping wine on his private beach. He has won money and fame as a bounty hunter, fighting pirate sea planes targeting tourist ships in the 1929 Mediterranean. He returns to civilization only to indulge in fine food and women.

Fio corrects him, “God was telling you it isn’t your time yet.”

“Laws don’t mean anything to a pig,” Porco says. Neither does honor, love of country, or even friendship. “I’m a pig. I look out only for myself. I fly for a paycheck.” Despite his pigheadedness, Porco is befriended by Fio, the heroine plane engineer, who asks him how he became a pig. “All middle-aged men are pigs,” Porco replies.

The cause of the curse is apparent. The individualistic pursuit of hedonic pleasure turns men into pigs. And yet, there apparently is a fate even worse than porcinity. When his old friend and current officer in Mussolini’s Italian air force asks him to return to active duty, Porco replies: “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist.” The spark of honor and capacity for virtue remains even in the pigheaded. Unlike whiteness in the woke mind, porcinity is curable.

Porco tells the story of a massive air battle in which he “thought about only himself” and fled his squadron. He escaped but then had a vision of his dead compatriots, rising to heaven. His survivor’s guilt is apparent. “Seems to me [God] was telling me I was a pig and deserved to be all alone.” No, Fio corrects him, “God was telling you it isn’t your time yet.” As is the case for most men, God’s purpose for Porco involves requiting a woman’s love and embracing marriage and responsibility.

Porco’s story is surprisingly resonant with Christian truth. The inclination toward porcinity, concupiscence, lies in all men. But the curse can be lifted in those who listen to God’s will for their lives, and sublimate their male strength, aggression, and violence into the virtues of chivalric masculinity.

We recently rewatched Porco Rosso on family movie night. No one changed their vote. But the kids did admit that it was pretty “fire.”

Legacy Disney sold the distribution rights for the several Miyazaki films they had dubbed and distributed, but you can stream many Studio Ghibli films right from Max in the U.S. and internationally from Netflix (except Japan). You can also purchase DVDs and Blu-rays from their site here.