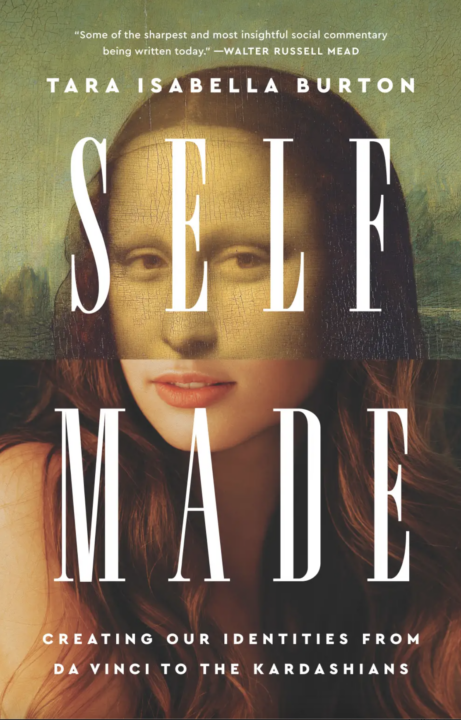

Word on Fire’s Andrew Tolkmith interviews Tara Isabella Burton on her new book, Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians.

Andrew Tolkmith: Much of your book explores the narrative of “Nietzschean self-creation” both in Europe and the United States. What exactly is “Nietzschean self-creation”?

Tara Isabella Burton: In my book, I argue that Nietzsche represents both the intellectual culmination and the aesthetic apex of the European “aristocratic” model of self-creation, one of the two strains I see as ultimately fused in contemporary narratives of self-making—and, perhaps, even a forerunner of this very fusion. For much of the concept’s early modern and nineteenth-century history—when artistic self-creation was understood, variously, as a prerogative of genius (i.e., the Renaissance model), an indefinable part of natural elegance (as in the dandy like Beau Brummell and Oscar Wilde), and a process of liberation from ordinary society and custom (and, in particular, the Catholic Church)—the idea had two main tenets. First, that self-creation was reserved for those who had an innate and inalienable natural quality, vaguely defined, that placed them in a kind of aristocracy not of birth or blood (or, importantly, money) but of spirit. Second, that one of the ways the self-creator manifested himself was through originality: through self-separation from the morals and mores of the common herd, stupid enough to follow “custom” blindly. (We see this taken to extremes, for example, in Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew, and in the writings of de Sade). Nietzsche’s vision of the Übermensch and the transvaluation values—both of which rendered explicit the implicit atheism (if not antitheism) of this new mentality—doubled as a kind of manifesto of self-making for a godless world: the closest thing to divinity was man himself and, in particular, those men who had the capacity—manifested in will and desire—to shape fungible, fundamentally meaningless reality in the image of what he wanted it to be. This model has become the normative one for contemporary American society: we are, at our core, most truly who we want to be, especially if that self-conception separates us from those we see as submissive, lesser, or sheep-like for following “the rules.”

What are the key differences between Europe’s historical approach to Nietzschean self-creation and America’s?

Traditionally—I’d say up until the twentieth century—the American model of self-creation (think Horatio Alger, Frederick Douglass, and the valorization of “bootstrapping”) sold itself as more democratic. Anyone, regardless of birth, circumstance, or, to a lesser extent, talent, could transform their lives and catapult their way through the social order—so long as they were willing to, as Douglass put it, “work! work!! work!!!” Personal effort, rather than innate specialness or divine favor, made the self-made man—an element that imbued the American model with moral weight: after all, if someone was poor or unsuccessful, according to this narrative, it must be because he didn’t try hard enough.

That said, I argue in my book that despite cosmetic differences, the American and European models had more in common than it might appear—something that fundamentally contributed to their ultimate fusing in our current narrative. Both stress the ideal that someone might display their fundamentally “authentic” self—which is to say, their aspirational self—outwardly as a means of legitimizing the inward truth of their worth, and both stress human will and effort, indeed desire, as the divinizing force in disenchanted human nature. The dandy whose outward sartorial display marks his innate superiority and the hardworking entrepreneur whose wealth speaks to his moral industry both see life outcomes as fundamentally reflective of the personality of the person living it—and see the “authentic” internal self as inextricable from carefully curated outward display.

We can say that self-creation has become part of “punching in,” a necessary and even mercenary part of everyday life in the internet economy.

The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor has argued that societies in the modern era have shifted from a mimetic interpretation of reality (i.e., truth and meaning are objective and individuals should conform themselves to that objective world) to a poietic one (i.e., individuals use the world to create truth and meaning). You seem to make a similar argument in your book: “Reality . . . must be something we compose and express for ourselves.” What are the benefits and drawbacks of such a shift?

Charles Taylor has been—and remains—a huge influence on my work: both on Self-Made and on my first book, Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World. I think his distinction is exactly right. And I don’t think it takes a lot of reading between the lines to see this, either. Both in America and Europe, self-creation was increasingly understood as a kind of magic, a self-divinization that allowed human beings (at least, some human beings) to come into their true inheritance as ultimate creators: the gods of their own worlds. There was a strong and deeply anti-clerical interest in the occult and the magical—a sense of finding the divine not in external authority or dogma but in the self and the self’s own internal power. We can see this both in Parisian dandy-occultism in writers like Sar Péladan, in America in the popularity of New Thought (a kind of proto-“manifesting self-help movement”), and, of course, in the techno-utopian writings of Stewart Brand, a pioneer of the 1960s counterculture, who believed that “we are as gods and we might as well get good at it.”

How prevalent today is the tendency to “self-create” in terms of personality, appearance, worth, and meaning?

Almost ubiquitous—at least among people in contemporary America who are online for personal and professional reasons (which is more and more common—about 90 percent of Americans have smartphones, and in the post-pandemic world, more than half of us do our jobs remotely at least in part). I think internet culture has taken this existing modern tendency and supercharged it—all of us are expected to “sell ourselves,” whether it’s on our “personal essays” for college applications, on dating sites, or on Twitter or Instagram for professional reasons if we have “personal brands” (intensified by the gig economy and attention economy alike, where we’re constantly attempting to create personae that might help us secure work, be it as an influencer or, in my case, a journalist). One can say that dandyism has been democratized—but, less optimistically, we can say that self-creation has become part of “punching in,” a necessary and even mercenary part of everyday life in the internet economy.

In your view, what are the major consequences of adapting a self-made lifestyle?

Dandies and glam rock stars (and tech billionaires spending $2 million a year on life extension like Bryan Johnson) aside—I think that the most major consequence, for the majority of us, is an increased and worrying focus on our internally felt emotions and desires as the primary authority for who we “really” are. The ubiquity of therapy-speak has only intensified this: we’re increasingly encouraged by all aspects of our culture to practice “self-care,” to set up “boundaries,” to cut out “toxic” people, to look inward, and, conversely, to see our social bonds and obligations to other people as sources of repression or societal “brainwashing”: that which arrests our development into our authentic selves, or which stops us from living our “best lives.”

To be clear—I don’t think that every dandy (or every entrepreneur, for that matter) does this. But I do think that the ideology of self-making, despite its liberatory potential, too often elides the other good, necessary elements of life, of what makes us us: our friendships, our families, our communities, our histories, all have roles to play in establishing our “authentic” selves. To treat our desires or internal narratives as exclusive sources of moral and spiritual authority is to forget that those internal narratives and desires themselves exist in and through shared stories, shared language, and cultural mediation—which does not validate or invalidate them but rather contextualizes them, and us, as beings that must contend with both incredible freedom and with facticity and givenness: biological and social alike. We are relational beings, and we are also mortal animals. These elements, too, are part of our authentic or “true” selves.

How has the internet become the merging force for all of the historical strands of self-making that have run through the Western world in the past five hundred years?

The internet takes so much of the implicit metaphysic of self-divinizing modernity—reality is what you make it, truth is something you can create or decide—and makes it literal. The attention economy and the algorithms that define everything from our news intake to the advertisements we see literally run on desire, quantified through attention, clicks, and the spending of money. The world of the internet runs on an engine of desire. And our shared reality—the one many of us spend hours a day on—transforms in accordance with that desire in a way that offline reality, physically embodied and geographically bounded, cannot do. The internet, depending on which way you look at it, represents the triumph of self-making—or the transformation of self-making from a strain of the modern imagination into modernity’s apotheosis.

How can Christians evangelize and promote a life of self-gift to a culture preoccupied with what you call the “ideology of the self”?

It would be a grave mistake, I think, to take a purely conservative approach to this problem: to treat all forms of internally felt identity as inherently misguided or wrong, or to argue for a return to a medieval conception of our political and social order as so God-given to the extent that none of us can truly escape our “place” in the world. Rather, I advocate for a balanced approach: one that celebrates both human creative freedom and the ways in which that freedom exists within a set of existing constraints, including our moral obligations to one another. As many of these existing constraints have lessened or vanished in our increasingly global, technologically advanced world, we might easily forget that our selfhood lies not purely in our desires or our creative freedom but also in the relationships we have to one another: on a political and personal level alike.

That said, something that I think the Christian can, and should, take from the story of self-creation is the very best of the self-making tradition, one both the dandies and entrepreneurs glimpsed in part. There is something irreducible and irreplaceable about us, individually, that cannot be reduced to a set of facts about our existence or to a detailed biography of our place of birth, our upbringing, our gender, race, class, and so on. That something, furthermore, may not be immediately apparent to other people, and one of the things we do as human beings is attempt to communicate that distinctiveness, our us-ness. We may not be purely self-creation beings, but I think we are all self-disclosing beings: storytellers who hunger to convey that distinctness within ourselves, and who do so with the narrative and social and linguistic categories we have available to us at that time. That awe for the dignity of each distinct human person, for the mystery that each of us contains within ourselves, that sense that we are all distinct and special and loved specially and distinctly by God as ourselves rather than as instantiations of a generic humanity—all this, I think, a Christian theology of self-making must preserve. The stories we tell about ourselves may be, as all stories are, imperfect when they come to ultimate truth—which few if any of us will ever be able to access—but they can help point us in the right direction. I like to think of the Gerald Manley Hopkins line about all of us shouting “out that being indoors each one dwells.” I like to think Oscar Wilde—a consummate dandy who ended his life as a Catholic—was trying to do that.