A Secular Apocalypse

By Rev. Robert Barron

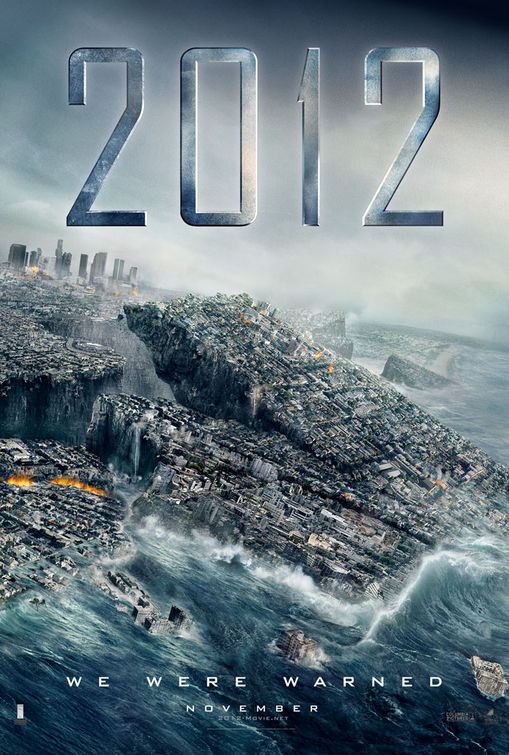

A wise professor of mine, Msgr. Robert Sokolowski, once commented that, with the rise of Protestantism and modernity, an integrated Catholicism blew up and its twisted pieces now litter the contemporary intellectual landscape. As I survey today’s cultural scene, I often think of Sokolowski’s observation: one can see Catholicism everywhere, but often in odd and distorted form. A very clear instantiation of this principle is Roland Emmerich’s new film “2012.” The movie’s premise is that massive sun bursts have led to the overheating of the earth’s core, resulting in major earthquakes, catastrophic eruptions, and continent-shifting tectonic shifts: in short, the end of civilization as we know it. A small group of scientists and politicians, who knew of the coming disaster, have organized a rescue operation—a flotilla of “arks”—so that a remnant of humanity, high culture, and the animal kingdom might be preserved. As the movie unfolds, we see the world implode, while a plucky family tries to make its way to the boats.

A wise professor of mine, Msgr. Robert Sokolowski, once commented that, with the rise of Protestantism and modernity, an integrated Catholicism blew up and its twisted pieces now litter the contemporary intellectual landscape. As I survey today’s cultural scene, I often think of Sokolowski’s observation: one can see Catholicism everywhere, but often in odd and distorted form. A very clear instantiation of this principle is Roland Emmerich’s new film “2012.” The movie’s premise is that massive sun bursts have led to the overheating of the earth’s core, resulting in major earthquakes, catastrophic eruptions, and continent-shifting tectonic shifts: in short, the end of civilization as we know it. A small group of scientists and politicians, who knew of the coming disaster, have organized a rescue operation—a flotilla of “arks”—so that a remnant of humanity, high culture, and the animal kingdom might be preserved. As the movie unfolds, we see the world implode, while a plucky family tries to make its way to the boats.

The notion of a world-ending catastrophe is, of course, Biblical. We hear of it in the story of Noah’s ark; it is predicted in the book of the prophet Daniel, and it is prominently featured in the book of Revelation, which brings the Bible to a close. There are two great sources for this religious intuition of the endtimes. First, we all know in our bones that the world is radically contingent, that it does not contain within itself the reason for its own existence. Things are, but they don’t have to be; they carry within themselves the heritage of non-being, and therefore, they are fragile, susceptible to destruction. The other inspiration for the apocalyptic is a keen sense of sin. We know that all of us are sinners and that our wicked ways have infected everything: institutions, political systems, families, societies, and cultures. And therefore, we feel that the world is under judgment and awaits a cleansing. It is important to note that both of these intuitions are tightly correlated to belief in God. The very contingency of the universe points to the existence of a non-contingent reality that sustains the fragile world in being, and the sinfulness of humanity is understood only in reference to some absolute criterion of good.

What we see in Emmerich’s film is a secular apocalypse, a re-telling of the Biblical story, but without God or any transcendent reference. In fact, God is not simply absent; he is aggressively eliminated. As the world falls apart, a number of people in “2012” turn to God in prayer, but they are, without exception, destroyed. A Hindu scientist, whose research first uncovered the coming apocalypse, folds his hands to pray, just before a tidal wave overwhelms him and his family. The President of the United States stays behind in the White House to invoke God’s help while the rest of the government is shuttled off to the ships. He goes on television to inform the country of the dire situation, and he invites them to recite Psalm 23, but when he comes to the line, “the Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want,” the communication is abruptly severed. The Cardinals of the Catholic Church kneel in ardent prayer in the Sistine Chapel, and just before the building collapses on them, they witness a great fissure running across the ceiling, passing directly between the fingers of God and Adam, separating divinity and humanity. And in a scene that will go down in the annals of cinematic anti-Catholicism, the Pope himself leads prayers from the loggia of St. Peter’s, while a huge throng looks on. The dome of the basilica totters, falls, and then rolls over thousands in the square below! Just in case we miss the point, Emmerich shows us the famous statue of Christ, which stands majestically on a hilltop overlooking Rio de Janeiro, crumbling to pieces.

Meanwhile, none of those who are making their way to the arks ever reference God. There is much talk of science and compassion and the preservation of culture, but no one in this groups prays, or speculates theologically on the unfolding calamity. (There is one religion that seems to meet with the director’s approval: a young Buddhist monk manages to shepherd his family on board one of the arks. But of course, Buddhism is a non-theistic religion. Buddhists hold that ultimate reality is not a creative and provident God, but rather the interdependent co-origination of all things).

In time, the worst of the crisis passes, and we see the arks making their way through placid seas, while on the screen there appears the new date: Year One. This is a fantasy that goes back at least as far as the French Revolution: once the old world has been cleansed of religion, people can let go of the antiquated dating system that commences with the birth of Christ. We then hear that the only continent that didn’t suffer inordinately from the apocalyptic meltdown was Africa; in fact, the scientists announce, it has arisen and its people preserved. Now say what you want about this, but what struck me was a certain unintentional irony: the continent where Christianity, and specifically Catholic Christianity, is growing most vigorously today, is not Europe or North America, but Africa. As the band of noble secularists arrives at the promised land, they will be met, not by Euro-skeptics, but by millions upon millions of Christians!

By the way, if you harbor any doubts as to whether I’m imagining all of this anti-religious sentiment, take a look at Roland Emmerich’s biography. I’ll give you one tidbit: in his house, he has a life-sized statue of John Paul II, laughing while he reads his own obituary. So don’t see this film. Instead, read the book of Revelation. It’s, of course, theologically richer, and also much less boring.