With this being Holy Week, my mind is drawn to the exquisite Tenebrist painting by Francisco de Zurbarán — “Agnus Dei” (or “Lamb of God.”) It’s not surprising that I would be drawn to the work of Zurbarán, often referred to as the “Spanish Caravaggio.” The depth and drama of Caravaggio’s work had grabbed me from the first slide I saw in my first at history class; there was a hypnotic appeal to the violent contrast of light and dark and tangible hyper-realism used to dramatic effect.

Holy Week, our time of Passover preparation, calls us to meditate on our unblemished Paschal Lamb. This is not to be confused with the cuddly lambs that greet us in the store aisles when we do our Easter basket shopping. The truth of what awaits the Paschal Lamb is harsh. Our Lord himself must have seen many similar lambs, awaiting their moment of sacrifice in the temple. We see a description of thousands of unblemished lambs sacrificed in the temple; an event that is hard to imagine, if one gives permission to the imagination to wonder about the harsh sights, sounds and smells. A moderate amount of blood has a distinct smell that is hard to forget, so much blood must have been overwhelming. The bloody sacrifice of thousands of lambs conjures a scene that even Quentin Tarantino would have difficulty recreating.

But what about the “Agnus Dei”? This Lamb is different. He is here to remind us of the one sacrifice that is necessary for mankind. The sacrifice that is to pay a debt that he does not owe for we, who owe a debt we cannot pay. Zurbarán has captured this calm moment, of the unblemished lamb, legs bound and prepared for sacrifice. All we must do is follow the story that we know is to come. As Dr. Brant Pitre notes in his book, Jesus and Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, “That’s what happens to Passover lambs. They don’t make it out alive.”

Zurbarán’s “Agnus Dei,” at the Prado Museum in Madrid, is on my wish list of paintings I hope to eventually see in person. As wonderful as high quality books are and the ease with which a Google image search takes us to all the great art of the world, there is nothing as good as standing inches away from the “real thing.”

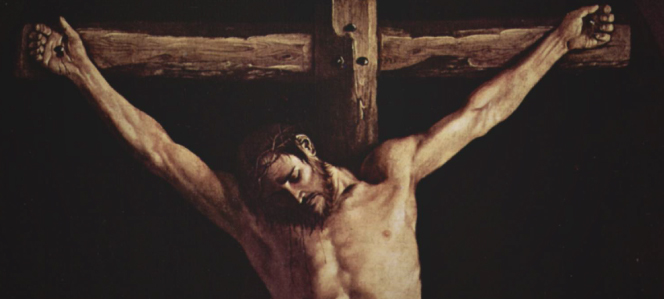

But I am privileged that I am able to see Zurbarán’s depiction of the continuation of the story that begins with the “Agnus Dei.” The Art Institute of Chicago possesses a treasure in Zurbarán’s “Crucifixion.” Containing all the beauty of Tenebrist skill that validates Zurbarán as the “Spanish Caravaggio,” I stand stunned in front of one of the most moving depictions of Our Lord’s sacrifice on the cross.

Of the plethora of artistic interpretations of Christ’s suffering on the cross, this painting is one of the best. The dark background not only obliterates whatever distractions show up in so many other works — not to denigrate the reality of the suffering and chaos surrounding the crucifixion, but to give the viewer the chance to focus totally on the moment in which the Lord accomplishes the act of his sacrifice for the sake of all mankind. The agony and desolation of the moment are brought to life for us now, in 2013, as real as they were when this painting was first seen in 1627. From the moment of the crucifixion to the 17th century and the 21st century, light is shone on the truth. We see the time darkness had fallen over the world, as we heard in the Palm Sunday Gospel reading this year, “It was now about noon and darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon because of an eclipse of the sun. Then the veil of the temple was torn down the middle. Jesus cried out in a loud voice, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit”; and when he had said this he breathed his last.” (Luke 23:44-46)

Chiaroscuro, amazing and entertaining in the most mundane subjects, is here at its most exquisite service as this sorrowful work brings the message that still “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” (John 1:5) There is dramatic darkness — but the light illuminates the hope.

This has not been the best Lent for me. As if Lent, like other secular celebrations, could be quantified by a checklist of successes and the feeling of “doing it right.” Under that type of criteria it has been a bad Lent. But I think I’ve been an active Catholic Christian long enough to know that each Lent is not an activity totally under my control. And my sense of floundering about and not doing it right is something I should not waste unfruitful thought on. There are daily distractions, followed by daily opportunities to start over. Plus, a child of mine is facing a potential diagnosis of a serious illness — with an appointment today, on Good Friday, an irony and a comfort that is not lost on me. This mother finds herself wobbling between redoubling her prayer and/or allowing a vivid imagination spin-off into scenarios where she should not go.

Reminders to refocus in the right direction come in random, yet blessed opportunities. While doing some shopping at a trendy big-box store, often fun, frivolous entertainment, my mind kept drifting unproductively to darker pressing matters; things beyond wanting to sing the theme from “Shortfall” while hustling through the checkout. The spiritual pitfall for me is the sense that if I worry enough I can make everything all right. The message to redirect came in the form of a pop song that was on the radio when I started the car. Never having paid much attention to the lyrics of “Crazy” by Cee Lo Green, this time some of the words were quite clear:

Come on now, who do you

Who do you, who do you, who do you think you are?

Ha ha ha, bless your soul

You really think you’re in control?

Well, I think you’re crazy….

And the cure for my crazy is to redirect my attention to the cross; to take these concerns to prayer and to leave them at the foot of the cross. The “Crucifixion”that those of us in Chicago are blessed to be able to visit is a visual aid in prayer of the highest quality. Any visit to the Art Institute should include a stop in the relatively quiet gallery that contains this splendid work. (How any visitors could continue yapping with bold, bouncy vocalizations while in the presence of such a powerful painting is hard for me to comprehend.) The dynamic of the sacrifice of the Lamb of God, in light and in shadow is so literally “breathtaking” that conversation in its presence is crass. It is fortunate that there is a bench for those who wish to stay, ponder and pray. It could only be better if Zurbarán’s masterpiece were in a room by itself; in as much of a pseudo-chapel that a secular institution could muster. There, one could meditate and appreciate the suffering and the solace of the one who paid a debt he did not owe for the salvation of the world.

There is a favorite quote from St. Edith Stein (St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross) that I keep on my desk at work. It begins, “Thy will be done,” in its full extent, must be the guideline for the Christian life. It must regulate the day from morning to evening, the course of the year and the entire life. Only then will it be the sole concern of the Christian. All other concerns the Lord takes over.” To forget that vital “fiat voluntas tua” leads to spiritual frustration and alienation. Or at the very least the need for a pop star to remind me that my thinking is craaazy! And the Saint ends with these words: “Whoever belongs to Christ must go the whole way with him. He must mature to adulthood: He must one day or other walk the way of the cross to Gethsemane and Golgotha.” To contemplate the beauty of Zurbarán’s “Crucifixion”is to be reminded that when we will walk to Golgotha, Jesus, the Light of the World, was there first and will be with us always.