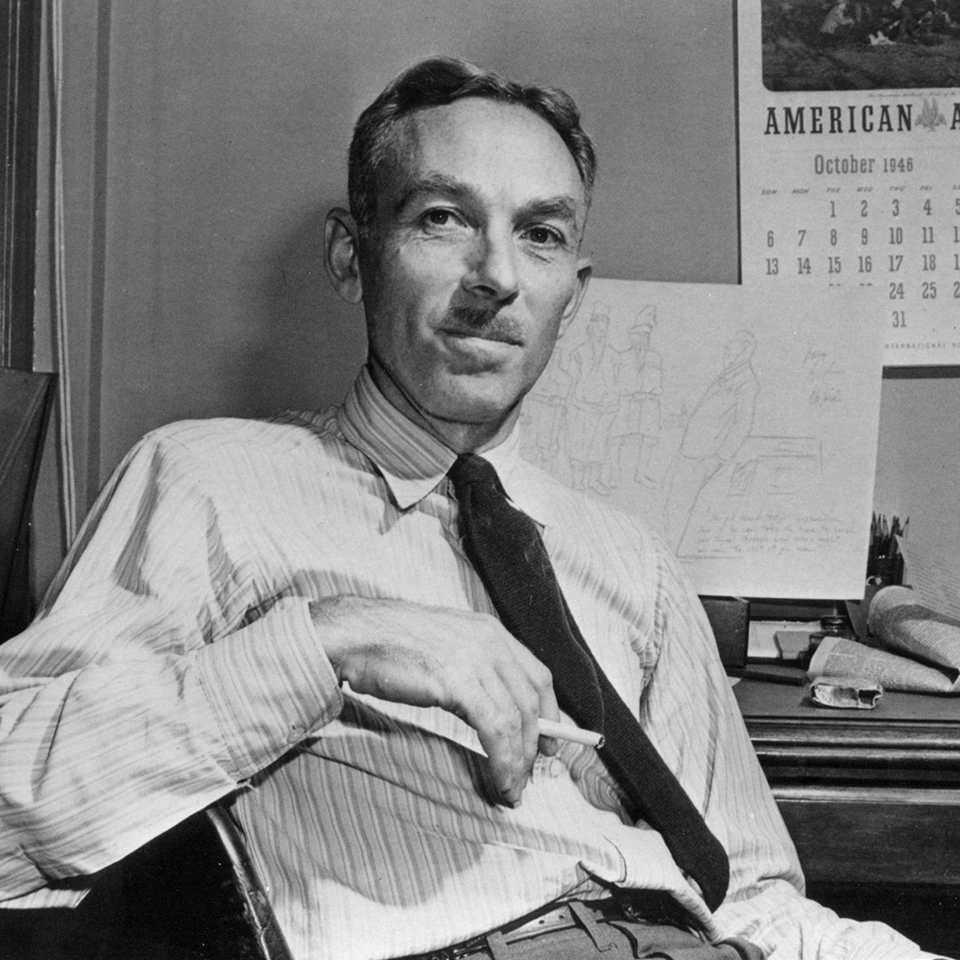

Recently, I started reading a collection of essays by E.B. White. Perhaps best remembered as the author of the classic children’s book Charlotte’s Web, White is also considered by many to be the greatest American essayist of the twentieth century. It’s not hard to see why. E.B. White is a master of the English language. His prose is fluid and effervescent, jam-packed with humorous metaphors and delightful turns of phrase. His tone is friendly and conversational, drawing the reader in and holding their rapt attention no matter how mundane the subject matter. His command of the essay form seems almost effortless.

The best essays elicit strong emotional responses from the reader. One case in point is his 1956 essay “Bedfellows,” which got a surprising rise out of me six decades after it was published.

In “Bedfellows,” White deftly segues from reminisces about Fred, his late Dachshund, into a discussion of national politics. His thoughts about freedom of the press and the expansion of the security state seem unnervingly prescient, demonstrating that few things in American political life ever truly change. But it is when he pontificates on the role of religious faith in public life that White hits on a topic as relevant and as caustic (if not more so) in the 2020s as it was in the 1950s.

White finds himself unsettled by a newspaper article on President Dwight Eisenhower’s view that prayer and religious faith are important pillars of a democratic society and the American way of life. White opines that “the implications of such a pronouncement, emanating from the seat of government, is that religious faith is a condition, or even a precondition, of democratic life. This is just wrong.” White goes on to say that American presidents can and should pray privately and even by words and deeds “demonstrate faith” but that they shouldn’t publicly “advertise prayer” or “advocate faith” because “such advocacy renders a few people uncomfortable.” Even six decades removed from the Eisenhower administration, doesn’t this all sound eerily familiar to contemporary ears?

Many people in Western society today view religion as little more than an individual private hobby; they become upset or indignant when it is promoted or preached in the public square. White asserts that “the concern of a democracy is that no honest man shall feel uncomfortable.”

But how, one asks, can democratic principles or the free exchange of ideas flourish under such a bizarre rubric? Unless one completely cuts oneself off from public discourse, it is inevitable that one will be made to feel “uncomfortable.” The beliefs, ideas, and convictions of others will not always be to our liking. And that’s fine! We should engage with ideas we disagree with, discuss them vigorously, not seek to silence or suppress them. If White had lived to see how the quixotic mission to ensure that one is ever made to feel offended or uncomfortable has led to the disturbing proliferation of “safe spaces” and “cancel culture,” an erosion of public discourse into rancorous recrimination and invective, and the desecration and vandalism of churches and the statues of saints, it’s doubtful that he would be pleased.

Religion in public life has always been a touchy subject in America. Although many of the Founders of our Republic were deeply religious men, they were also heavily influenced by the values of the Enlightenment, which, among other things, championed reason over and above faith and advocated the strict separation of church and state. White reveals himself as an inheritor of the Enlightenment tradition when he balks at the idea that religious faith could possibly be a precondition, or stabilizing pillar, of democratic society. Americans rightly find repugnant the idea of an official state-sanctioned church, but for most of the nation’s history its citizens also took for granted the notion that the United States was founded upon Judeo-Christian principles of justice and the fundamental rights of the human person. Thomas Jefferson, by no means an orthodox believer, stated unequivocally in the Declaration of Independence that “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” This is a remarkable statement. For the vast majority of human history, the basic equality of human beings as children of God with irrevocable rights was emphatically not recognized as self-evident. Only on the foundation of the divinely revealed Scriptures of the Judeo-Christian tradition could these ideas find purchase.

Among E.B. White’s concerns was that religious faith would be made “one of the requirements of the accredited citizen.” While I certainly agree that one need does not need to be a believer in order to participate in a democratic society, I think that all Americans should acknowledge that democratic principles and institutions ultimately find their basis in the Judeo-Christian faith tradition. When this is forgotten, when religious faith wanes, it can only be to the detriment of our society.

This principle is plain to see for anyone who takes even a passing interest in public affairs. In the sixty-plus years since E.B. White wrote “Bedfellows,” religious faith in America has been on a precipitous decline, with a corresponding erosion of moral values. Nature abhors a vacuum. If Christianity is rejected as the basis of our social life, some competing ideology is bound to take its place. To quote from the Catechism of the Catholic Church number 2257: “Every society’s judgement and conduct reflect a vision of man and his destiny. Without the light the Gospel sheds on God and man, societies easily become totalitarian.”

E.B. White chided Eisenhower for insisting on the vital role of faith in a democratic society, but it is important to remember what Eisenhower had seen as the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe during World War II. On April 12, 1945, Eisenhower visited the concentration camp at Ohrdruf, Germany. There he was personally exposed to the horrific crimes of the Nazi Party which sought to supplant Christianity with a racist blood and soil ideology that promoted worship of the state. As president, Eisenhower confronted the might of the Soviet Union, which imposed its atheistic communist system over half of Europe through violent oppression. The totalitarian atheist regimes of the twentieth century serve as a warning that when faith is sidelined—abandoned in favor of godless ideologies—democracy and respect for human dignity quickly evanesce. It is surprising that a brilliant man such as E.B. White failed to appreciate this reality.