Equanimity is calamity’s medicine.

—Publilius Syrus

“Cultivate, then, gentlemen, such a judicious measure of obtuseness as will enable you to meet the exigencies of practice with firmness and courage, without, at the same time, hardening ‘the human heart by which we live.’”

Almost every medical student of my generation (and I’m not that old) will recall the time a physician mentor quoted Sir William Osler’s seminal speech, Aequanimitas, offered to the graduating class of the Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1889. In it, Osler, the “Father of Modern Medicine,” extols the virtue of Aequanimitas—that is, equanimity—in the successful practice of medicine.

But what exactly is equanimity?

Equanimity is a coolness, a steadiness, an evenness of temper that allows a person to bear the ups and downs of life. Its relevance to medicine is plain to see. If a hospitalized patient is “coding” (having a cardiac or respiratory arrest) and you are tasked with efforts (in charge of a team of five to fifteen) to resuscitate them, you need equanimity. If you walk into an exam room and you can instantly tell that the patient is angry about something, you need equanimity. If you bear the responsibility to reveal a troubling finding or devastating diagnosis to a patient and their family, you need equanimity.

Physicians, to be sure, must possess equanimity.

But so must everyone else.

In Evelyn Waugh’s masterpiece, Men at Arms, Mr. Crouchback was a delightful, older, aristocratic widower who earnestly loved his Catholic faith and his storied English family tradition. And yet, when his beloved estate of Broome was lost (“without extravagance or speculation, his inheritance had melted away”), Mr. Crouchback (without affectation) maintained his equanimity. Waugh illustrates equanimity brilliantly.

[Mr. Crouchback] was an innocent, affable old man who had somehow preserved good humor—much more than that, a mysterious and tranquil joy—throughout a life which to all outward observation had been overloaded by misfortune. He had like many another been born in full sunlight and lived to see night fall. . . .

Only God and [his son] Guy knew the massive and singular quality of Mr. Crouchback’s family pride. He kept it to himself. That passion, which is often so thorny a growth, bore nothing save roses for Mr. Crouchback. . . .

He had a further natural advantage over Guy; he was fortified by a memory which kept only the good things and rejected the ill. Despite his sorrows, he had a fair share of joys, and these were ever fresh and accessible in Mr. Crouchback’s mind. He never mourned the loss of Broome. He still inhabited it as he had known it in bright boyhood and in early, requited love.

In his actual leaving home there had been no complaining. He attended every day of the sale seated in the marquee on the auctioneer’s platform, munching pheasant sandwiches, drinking port from a flask and watching the bidding with tireless interest, all unlike the ruined squire of Victorian iconography. “Who’d have thought those old vases worth 18 pounds? Where did that table come from? Never saw it before in my life. . . . Awful shabby the carpets look when you get them out. . . . What on earth can Mrs. Chadwick want with a stuffed bear?”

Even after losing his family home at Broome, Mr. Crouchback cheerfully returned once per year to have a requiem Mass sung for his ancestors. His walk down High Street to and from his former estate was punctuated by the warm greetings of old friendly shopkeepers and young passersby. Mr. Crouchback was a picture of equanimity.

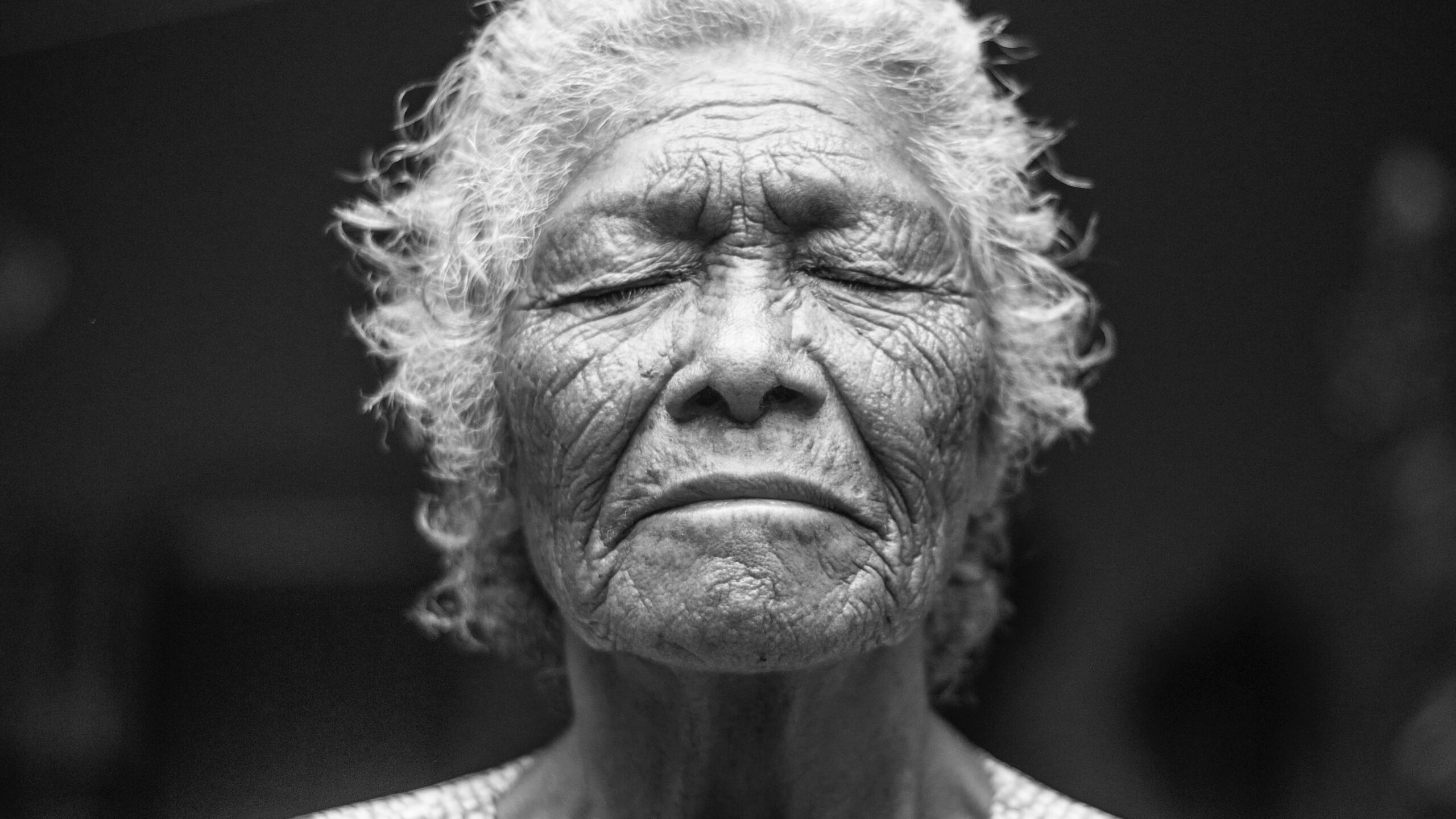

The beginning of William Wordsworth’s 1802 poem Old Man Travelling unfolds a rich portrait of equanimity:

The little hedge-row birds,

That peck along the road, regard him not.

He travels on, and in his face, his step,

His gait, is one expression; every limb,

His look and bending figure, all bespeak

A man who does not move with pain, but moves

With thought—He is insensibly subdued

To settled quiet: he is one by whom

All effort seems forgotten, one to whom

Long patience has such mild composure given,

That patience now doth seem a thing, of which

He hath no need. He is by nature led

To peace so perfect, that the young behold

With envy, what the old man hardly feels.

“All effort seems forgotten.” “Patience now doth seem a thing, of which he hath no need.” “To peace so perfect, that the young behold with envy, what the old man hardly feels.” Wordsworth writes what we all think of the person we sense is at peace—“I want some of that.” But then Wordsworth unveils the reality behind the first impression:

—I asked him whither he was bound, and what

The object of his journey; he replied

“Sir! I am going many miles to take

A last leave of my son, a mariner,

Who from a sea-fight has been brought to Falmouth,

And there is dying in an hospital.”

Is this man’s composure a facade? A ruse? An act of denial or delusion? I don’t think so. To be sure, I think he is grievously pained by the imminent death of his son, but he also has a sense of proportion—of equanimity—amidst the complexity of life and the inevitability of death that comes from both knowing feasts and revelry as well as gall and wormwood.

Years ago when the Pope visited America, there circulated a photo of a tangle of people on the roadside of the coming papal procession. They were all obsessed with their phones. As they frantically adjusted their settings to snap that perfect picture of the passing pontiff, there in the front with hands atop the barricade was a diminutive old woman with a big smile on her face. No phone. No camera. No pushing or shoving. Just a lady at ease drinking in the moment. Certainly, most of the others will have to comb through their photo album just to see what this lovely lady—awash with equanimity—saw firsthand.

Equanimity is so delicious—so enviable—when you see it. . . because when you see it, you want it. It is composure and poise, maturity and sensibility, an interior space unruffled by exterior chaos. I think it is one of the very things that drew (and still draws) people to Christ and his saints. Equanimity is not dispassion (because they care greatly), but a deep rootedness in the permanent things. It is not stoicism, but keen perspective. It is not having all the answers, but trusting that God does.

Faith does wonders for the cultivation of equanimity. Eminent philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once admitted, “Religion is, as it were, the calm bottom of the sea at its deepest point, which remains calm however high the waves on the surface may be.” Somehow, beyond the permanence of mountains and the steadiness of the sea, it is the kneelers and the incense, the prayers and the sacraments, the dogmas and the truths of the timeless God that foster equanimity in my soul (and, I hope, yours).

So what, exactly, is equanimity? Osler characterized it. Waugh illustrated it. Wordsworth unfolded it. The little old lady on the side of the parade embodied it. And the Church fosters it. But perhaps my favorite description comes from English wit and writer P.G. Wodehouse. “The true philosopher,” Wodehouse writes, “is a man who says ‘All right,’ and goes to sleep in his armchair.”

Not perfect.

But close.