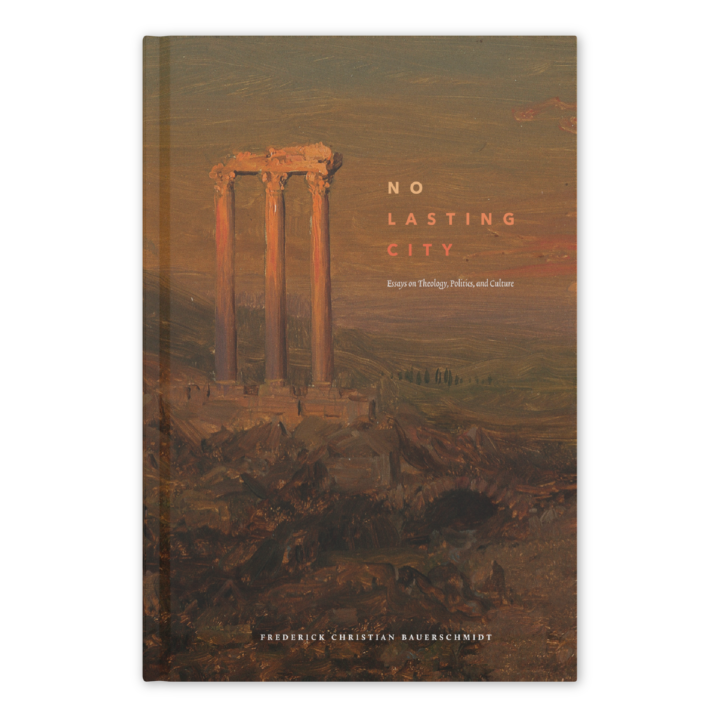

The new book from Word on Fire Academic, No Lasting City, offers essays written over a twenty-five-year period that explore the relationship between theology, politics, and culture.

Drawing on the Christian theological tradition and engaging thinkers from Augustine and Julian of Norwich to Max Weber and Michel de Certeau, readers experience a depiction of faithful engagement with politics and culture that has robustly Christological contours. The following is an excerpt from Thesis #5 in Chapter 1: “Confessions of an Evangelical Catholic.”

The Christian understanding of history is apocalyptic rather than progressive.

In his encyclical Evangelium Vitae, John Paul II wrote that “life is always at the center of a great struggle between good and evil, between light and darkness.” This sort of apocalyptic language makes some uncomfortable, striking them as “Manichean” in its stark opposition of good and evil, light and darkness. But the loss of the apocalyptic perspective brings with it the loss of a proper understanding of human history and the Church’s place within it.

First, the apocalyptic perspective does not mistakenly see humanity’s pilgrimage through history as fundamentally one of “progress.” We can, of course, speak of progress in a certain sense: human knowledge increases, and with technological advances, things become possible that were not possible before. And one should not slight such things. But the apocalyptic perspective asks whether an increase of knowledge is the same as an increase in wisdom. Do technological advances necessarily correlate with human flourishing? Most importantly, do these sorts of progress hasten the consummation of history? What we have here is something of a replay of the debate in the 1950s and ’60s between the “incarnational” and the “eschatological” approaches to history, debates that were important in the drafting of Schema 13 [which later became Gaudium et Spes]. Put no doubt oversimply, the question is whether the fulfillment of history develops gradually from within history via human activity or whether history’s fulfillment comes crashing in upon it with the return of Christ in glory. The latter view does not deny that Christians must act to alleviate suffering by attending to both the sources and the effects of injustices, yet it maintains, as Louis Bouyer put it, “that all this work will, so far as we can judge from the hints of divine revelation, never be successful in the sense of establishing any lasting and universal Christian state of things.”

. . . the endurance of evil is not the same as passive acceptance.

Second, the apocalyptic perspective reminds us that we are in the midst of a struggle between cosmic forces of good and evil. It is crucial, however, that such a claim be accompanied by a nonprogressive view of history, for we ought not to think that the evils of today are any greater or less than the evils of the past. John Paul’s statement that life is always at the center of a struggle between good and evil serves as a salutary warning against those who would claim that our historical moment presents a unique opportunity and that we must act now to implement some scheme that would bring about a comprehensive elimination of evil. Evil is something that must be endured until it consumes itself. But at the same time, John Paul’s emphasis on struggle indicates that the endurance of evil is not the same as passive acceptance. Indeed, the Letter to the Ephesians is at pains to remind us that it is because “our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness” that our proper means of combat is “to take up the whole armor of God,” which consists not in swords or guns or five-year plans but in truth and righteousness and whatever will make us ready “to proclaim the gospel of peace” (Eph. 6:12–15). As the book of Revelation makes clear, Christians are not called to success but to perseverance, and faithful Christian endurance in the time-between-times is resistance to evil.

No doubt these theses will one day seem as dated as the optimistic predictions about the fruit issuing from the Church’s embrace of the modern world that were penned in the years following the Second Vatican Council. William Portier points out well that evangelical Catholicism is a response to a particular set of historical circumstances and, as Foucault would no doubt wish to remind us, if the forces that produced evangelical Catholicism were to disappear, then it too would be erased, like a face drawn in the sand at the edge of the sea. However, inasmuch as it is an attempt to be faithful to the Gospel of Christ by fostering faith, hope, and love—that is, inasmuch as it is truly evangelical—then I believe that it has enduring value.

Catholics emerging from their ecclesiastical subculture rightly felt liberated from narrow intellectual, cultural, and social confines. But among some Catholics, particularly those who have known nothing but life outside the subculture, it is beginning to appear that we have simply exchanged one set of intellectual, cultural, and social confines for another—the confines of the postindustrial bourgeoisie. Some of us wonder if the real choice is not whether we should choose confinement or liberation, as if human life were not always lived under some form of discipline, but rather which form of discipleship will lead to true freedom, which form of life is truly a human one.

Word on Fire Academic’s No Lasting City offers the stories of Flannery O’Connor, the paintings of the Flemish Primitives, the curricula of medieval universities, and modern accounts of mystical experience all serve as points by which the path of God’s pilgrim city is charted, as a way both of understanding our past and present and of orienting us toward our hoped-for homeland.