When NASA sent out the two Voyager probes in 1977, they attached a 12-inch “Golden Record” to each spacecraft to communicate the great story of life on earth to whatever (or whoever) might be out there. The gold-plated discs included the sounds of laughter, diagrams of DNA strands, and a selection of music summarizing the human experience.

Among the masterpieces of Bach and Mozart was a standalone track: a gospel tune about the night before Christ’s crucifixion, sung without words over a slide guitar—a song Ry Cooder called “the most soulful, transcendent piece in all of American music.”

The original 1792 lyrics are powerful in their own right: “Dark was the night and cold was the ground / On which the Lord was laid / His sweat like drops of blood ran down / In agony he prayed.”

But when Blind Willie Johnson sat down and hummed and moaned “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” in Dallas in 1927, he inscribed the hymn—and himself—into music history. The song haunts the shadowy margins of human life where words fail; it is the sound of naked sorrow and utter heartbreak, and captures the penitential spirit of Lent and the sacrificial drama of Holy Week with aching precision.

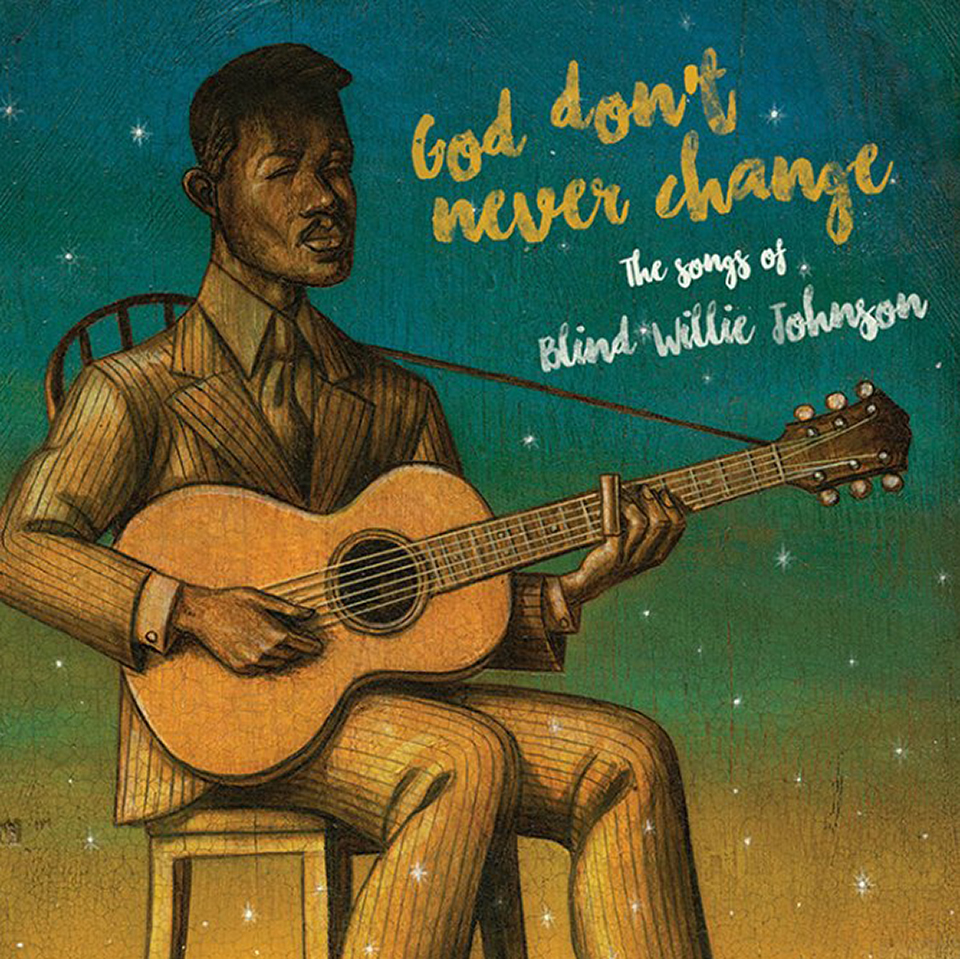

But who was Blind Willie Johnson? In the liner notes of a recent cover album, God Don’t Never Change: The Songs of Blind Willie Johnson from Alligator Records, blues scholar Michael Corcoran notes that not a whole lot is known about the mythical figure. Even his blindness is a mystery. (The story goes that a stepmother threw lye water in Willie’s face when he was a child “and put his eyes out.”) “Unlike the ‘songsters’ who mixed blues and gospel, Johnson sang only religious songs, which explains a big part of his relative obscurity,” Corcoran writes. “His raspy evangelical bark and dramatic guitar were designed to draw in milling, mulling masses on street corners, not to charm casual roots rock fans decades later.”

Still, Johnson’s influence can be felt literally everywhere in music. “You can put the artistic results of Blind Willie Johnson’s December 3, 1927, session in the same league of Best Studio Days Ever,” Corcoran explains. “Blind Willie Johnson’s six tracks included ‘Jesus Make up My Dying Bed’ (covered by Bob Dylan as ‘In My Time of Dying’ in his 1962 debut LP), ‘Nobody’s Fault But Mine’ (Led Zeppelin), ‘Mother’s Children Have a Hard Time’ (Eric Clapton) and ‘If I Had My Way’ (Peter, Paul & Mary’s debut LP).”

The eleven hand-clapping, soul-shaking renditions of Johnson’s songs on God Don’t Never Change not only honor his legacy but also make for a good Lenten soundtrack. A diverse ensemble brings together a variety of styles and sounds; but from start to finish, the album is held together by the gritty musicality, wild energy, and spiritual urgency that made Blind Willie Johnson’s music so unique.

Tom Waits—whose voice has been described by critic Daniel Durchholz as being “soaked in a vat of bourbon, left hanging in the smokehouse for a few months, and then taken outside and run over with a car”—kicks things off with “The Soul of a Man.” The crackle of vinyl, the animated growl, and the female backup are all perfect hat-tips to Johnson’s style. Waits returns later with a drum-heavy cover of “John the Revelator,” which could very well be a B-side from Bone Machine, testifying to the influence the itinerant preacher-singer has had on him.

Waits’ opener melts into the Louisiana drawl of Lucinda Williams, who also contributes two songs to the album: “Nobody’s Fault but Mine” and the title track “God Don’t Never Change,” both of which add deep-fried electric bounce to Johnson’s bluesy admonitions.

As fun and interesting as these covers are, the power of Blind Willie Johnson’s music is its simplicity: a rumbling voice, an expert slide guitar, and the Good News of the Gospel. Two standout tracks—Luther Dickinsen’s “Bye and Bye I’m Going to See the King” and Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks’ “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning”—basically leave Johnson’s formula unaltered. “His music is so of the earth that it still sounds completely modern,” Dickinsen explains. “It’s timeless and like nothing else ever recorded.” Trucks sees it as more than timeless: “He’s one of only a handful of musicians who really feel like sacred music to me.”

If the other tracks deviate from Johnson’s sound, they bear witness to his enormous influence in other genres: not just blues, but gospel (Maria McKee’s “Let Your Light Shine on Me”), rock (Cowboy Junkies’ “Jesus Is Coming Soon” and Sinead O’Connor’s “Trouble Will Soon Be Over”), and soul (The Blind Boys of Alabama’s “Mother’s Children Have a Hard Time”).

The album ends with that transcendent American classic—but with a twist. Rickie Lee Jones’ scratchy voice and acoustic guitar, topped off with horns and tambourines, transforms “Dark Was the Night” into something more gentle and tangible, while still capturing the loneliness and agony of Christ in the garden. It’s an appropriately restful end to a rollicking homage.

In September 2013 Voyager 1 ventured beyond our heliosphere, becoming the first manmade object to reach interstellar space. Billions and billions of miles away, Blind Willie Johnson’s voice stands ready to teach the entire cosmos about the soul of man.

Back here on Earth, he’s scarcely just begun.