The singular objective of a Christian’s life should be to attain sanctity. God, through the Incarnation of his son, has given us all we need to accomplish this goal. The traits of spiritual perfection that we are called to cultivate are called virtues, and we acquire them through meeting life’s challenges in cooperation with the graces that are offered to us through Jesus’ Passion. Ultimately, each day is an opportunity to conform our will to the Divine Will—to the person of Jesus Christ himself.

Saints are our heroes of the Christian past—those who have been recognized by the Church as having attained this kind of heroic virtue. Many, too, are those in more recent memory. These saints don’t exist only in the distant past, represented by flowery paintings on holy cards. There are saints and martyrs living among us even now.

The Venerable Jerome Lejeune, who died in 1994, has not yet been proclaimed a saint by the Church, but the process is well underway. After extensive investigation into every aspect of his life, he has been given the title “Venerable” as a public affirmation that he lived a life of heroic virtue. This proclamation is a big step toward canonization. The Church now places him before us as a witness to Christ and as an intercessor in our times of need. I would especially recommend him to all those who have family members with genetic intellectual and developmental disabilities. Pray to him for his assistance, and also pray that one day, before long, he will be named a “Blessed” and then eventually a saint.

Jerome Lejeune is unique among those who have been put forward to the Church for consideration for sainthood. He wasn’t a priest or religious. He was a Catholic layman whose life was guided by his faith. He developed a close friendship with St. John Paul II, but few would have considered him a saint in the way we did St. John Paul II, even before the cries of “Santo Subito” rang out after his death. His opponents in the abortion debates feared him. They saw him as a Catholic radical, and some walked away from debates with him, knowing they could never defeat his reasoning. Once, during a televised debate about the impending anti-life laws in France, Mrs. Lejeune was listening from backstage and overheard one person say, “The bastard! He is too good. They won’t invite him again!”

Hate the disease, love the patient . . .

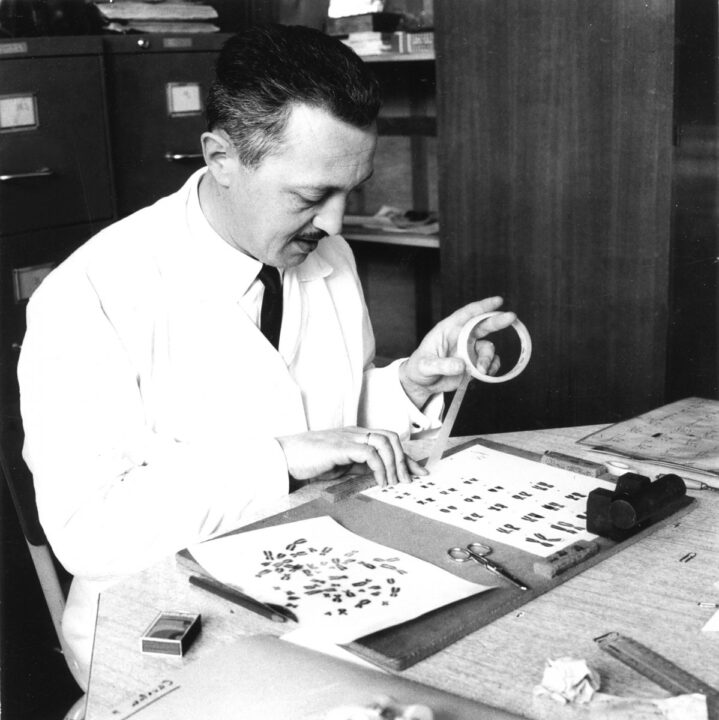

Lejeune was a dedicated family man with five children. He was a practicing physician who saw patients every day in his clinic and a brilliant medical researcher who hoped to discover a “cure” for Down syndrome in his lab—at least when he wasn’t traveling the world speaking at scientific conferences or representing the Vatican in nuclear disarmament talks.

Lejeune’s notoriety first emerged out of his scientific discovery that Down syndrome was caused by an extra copy of the twenty-first chromosome. He became a star in the medical universe, and his notoriety brought him many honors—at least until the crowds turned against him, like the crowds in Jerusalem yelling, “Crucify him, crucify him!”

Venerable Jerome Lejeune’s heroism in his fierce defense of life came at considerable personal loss. When he received the William Allen Memorial Award in San Francisco in 1969, he was just 43 and at the top of his fame. There was no higher award a geneticist could receive. Dr. Lejeune was warned to be careful by some colleagues before he ascended the dais to deliver his acceptance speech, but he disregarded their advice and spoke boldly to an audience of his peers against the use of genetics to identify and dispose of children conceived with genetic anomalies. He knew what the cost would be, and he was right. He returned to his seat with the audience in silence. From the time of his discovery in 1958 to this 1969 “To Kill or Not to Kill” speech in San Francisco, he had spoken at fifty scientific conferences in the US, but in the 5 years following, he only received five invitations. Instead of being asked to join scientific conferences, he was increasingly asked to participate in pro-life events, including in 1989 when he was asked at a moment’s notice to fly from Paris to Maryville, TN to testify in the first legal challenge to the personhood of frozen embryos.

As Jerome Lejeune’s advocacy for the unborn increased, the funding for his research decreased. As one who never cared at all for money, he found himself crossing the globe in search of funding that would allow him to continue to maintain his lab. The more the push toward abortion intensified, so did his pro-life witness.

For medical doctors today, there could be no more appropriate patron saint. Jerome Lejeune knew the limits of medicine and science, but he also knew that there were no boundaries on love. He saw all his patients—and even his opponents—as children of God and worthy of respect. Unlike many in his profession, he knew that where there is suffering you cannot heal, you kneel before the mystery of God’s love and simply love the patient. In so doing, Lejeune shared God’s love with others. Hate the disease, love the patient—that was a motto he lived by each day.

The Venerable Jerome Lejeune saw that what was missing in the practice of medicine was humility. In a meditation that he wrote on the contribution of the three magi to the revelation of the birth of Jesus, he reflected on two dispositions that he said are required to find God: the desire of the magi, and the humility of the shepherds. He knew that the magi were successful on their quest to follow the star because they had embraced the humility of shepherds. It was the absence of pride and their desire to find Jesus that enabled them to consult the theologians to get answers to what science could not provide—the exact place of the Holy Child’s birth. In continuing his reflection, he wrote:

The only dignity of scientists is to have the audacity to say: ‘Really, I do not know that, I am not competent.’ . . . Scientists are absolutely not supposed to set up barriers. The thing that tells us what is good or evil is not science, but morality. And if science does not submit to morality, science goes mad. . . . It belongs to science to say that a human being is a human being, and then morality tells you: therefore, it is necessary to respect the human being.

Venerable Jerome Lejeune, pray for us, that we might always desire the same light that drew the three wise magi in humility to the infant Lord. May we seek the same wisdom that formed you in God’s truth and the same strength you embodied in standing strong in defense of life and against the culture of death.

Learn more and support the work of the Word on Fire Venerable Jerome Lejeune Fellowship here.