The end for which we are created invites us to walk a road that is surely sown with a lot of thorns, but it is not sad; through even the sorrow, it is illuminated by joy.

—Pier Giorgio Frassati

On one difficult night a few years ago, when I seemed to be dealing with a succession of battles with pneumonia or bronchitis, the strangest thing happened to me. I was lying in bed in the wee small hours and found my muscles going into odd sorts of rolling contractions, from the lower abdomen to mid-ribcage and all around my back.

Because I hate taking medicines or pills unless I absolutely have to, I tried all the usual alternatives: slow, deep breathing. Prayer. Meditations on the Communion of Saints and those great examples of living through periods of illness and pain. Making an offering of the pain to Christ crucified in the discipline of “offering it up”—which gives our sufferings, large and small, both purpose and meaning.

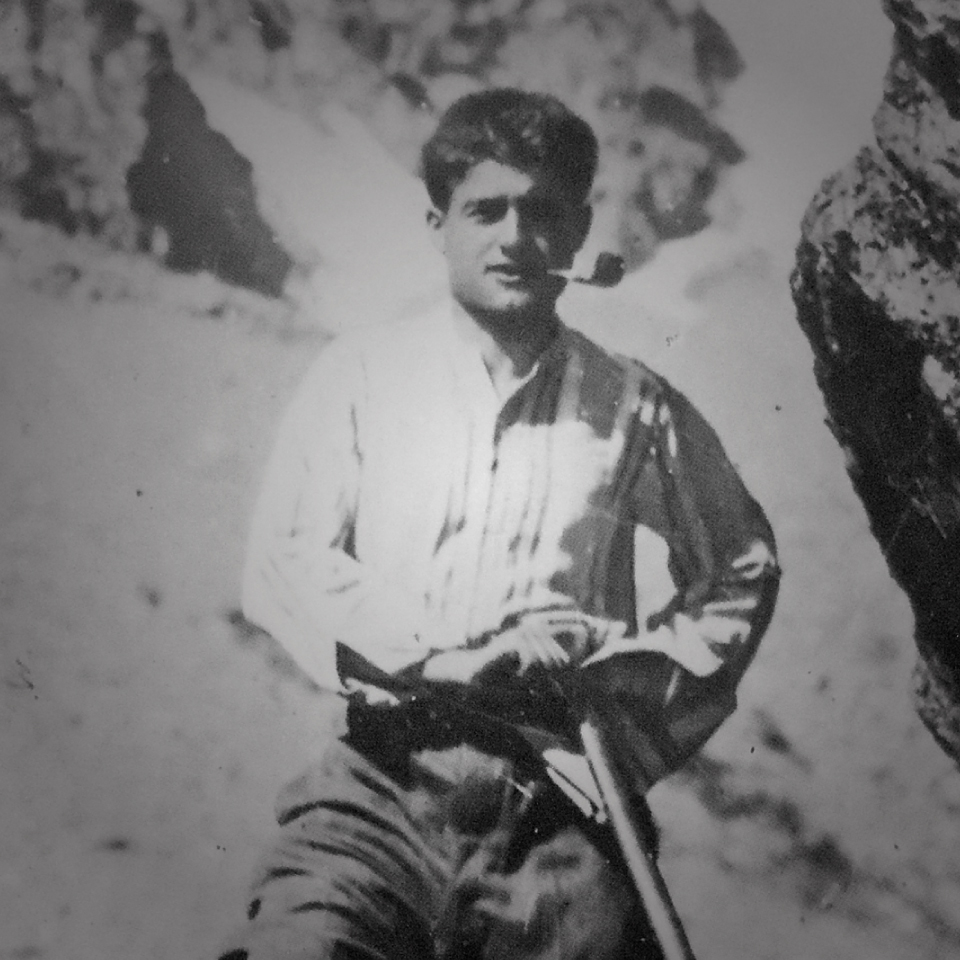

I thought about Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati, the Third Order Dominican who fascinates me because he was so clearly a normal, energetic young man. He skied and danced and smoked a pipe and dated and had a gregarious, joyful social life, yet he lived his faith heroically, and even managed to chase off fascists.

Today we would call Pier Giorgio “privileged,” but he had a quietly hands-on commitment to the underserved and marginalized:

Although the Frassati family was well-to-do, the father was frugal and never gave his two children much spending money. What little he did have, however, Pier Giorgio gave to help the poor, even using his train fare for charity and then running home to be on time for meals in a house where punctuality and frugality were the law. When asked by friends why he often rode third class on the trains he would reply with a smile, “Because there is not a fourth class.”

When he was a child a poor mother with a boy in tow came begging to the Frassati home. Pier Giorgio answered the door, and seeing the boy’s shoeless feet gave him his own shoes. At graduation, given the choice by his father of money or a car he chose the money and gave it to the poor. He obtained a room for a poor old woman evicted from her tenement, provided a bed for a consumptive invalid, supported three children of a sick and grieving widow. He kept a small ledger book containing detailed accounts of his transactions, and while he lay on his death bed, he gave instructions to his sister, asking her to see to the needs of families who depended on his charity. He even took the time, with a near-paralyzed hand, to write a note to a friend in the St. Vincent de Paul Society with instructions regarding their weekly Friday visits. Only God knew of these charities; he never mentioned them to others.

Upon his death his family was floored to find thousands showing up for his funeral.

He was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1990. At World Youth Day gatherings since then, Pier Giorgio’s relics are often present, as is his memory, because he is an almost irresistible inspiration to young Catholics.

All those years ago, as I was getting through a painful night, I also thought about Pier Giorgio because of his odd death. In 1925, as his grandmother (who taught him his catechism) lay dying down the hall, no one was checking in on Pier Giorgio, who had taken to his bed with some muscle aches that seemed like the flu. Turned out he had contracted an aggressive strain of polio, and within six days—before his distracted family even realized how unwell he was—the twenty-four-year-old was dead.

In my pain that night, I wasn’t worried about dying, of course, but as I worked to get my muscles oxygenated through breathing and light effleurage, I asked Pier Giorgio to pray for the comfort of everyone who was struggling with pain and unwilling to wake up their household about it. We were together in prayer—friends who prayed together—in the Communion of Saints.

On the anniversary of his death, I’m glad to introduce you to a young twentieth-century Beato who will need a miracle credited to his prayers before he can be called Saint—and there is one currently being looked at.

I like Pier Giorgio a lot. I like his spunk and his laughter, and the way he managed to live a serious life of faith without becoming freakish or over-scrupulous about it. I like that we have actual pictures of a faithful young man enjoying wine and a pipe and wearing a silly hat at a birthday party among friends.

It’s fun to imagine that, were he a young person today, he’d be standing on a table belting out a tune on karaoke during a festive time. Joy is a product of faith we too often do not recognize or celebrate in the holy.

Dare I say, he reminds me—both in his joyful temperament and his social concerns—a little bit of my sons. Just a little, you understand. But I think they would have been good friends, the sort to go to the tobacconist to mull over new blends for their pipes, and then perhaps pop by a local parish to make a visitation or pray a decade of the rosary, together, and then head out to a pub.

Young Catholics—young male Catholics, especially—really need such an example of faith lived within a well-rounded and normal sort of life.

Once, as he exited a church with his rosary in his hand, someone said to him, “So, Pier Giorgio, you have become a religious fanatic?” He calmly answered, “No, I have remained a Christian.”

In 1925, he wrote to his friend Isidoro Bonini, “I would like for us to pledge a pact that knows no earthly boundaries or temporal limits: union in prayer.”

It was Pier Giorgio’s desire that his friends—including you and me—remain united in prayer, whether it is time to submit to the cross and deal with our pains, or to just have a party with our friends.

Blessed Pier Giorgio, pray for us!