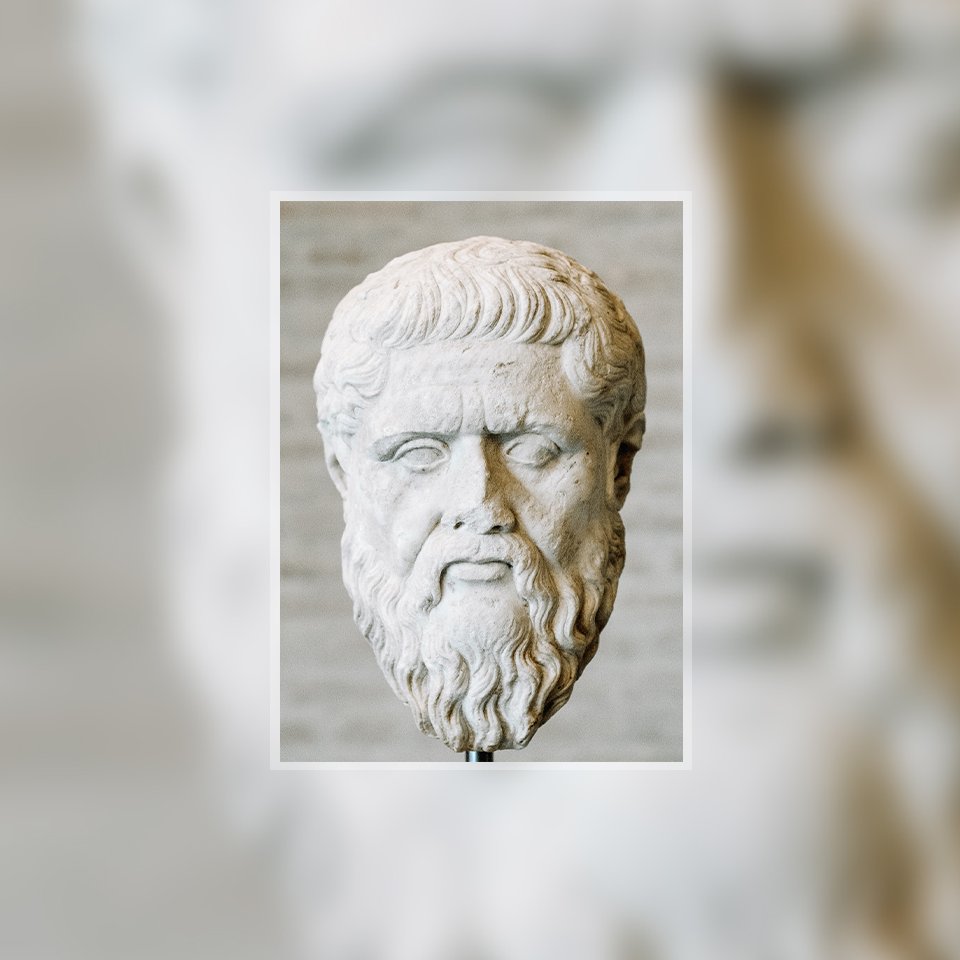

On my desk, I have a little bust of Plato. And every now and then I found it staring right at me as if it had something to say. My attempts to get it to finally speak always went unanswered; in fact, the silence was deafening. I almost gave up but recently something changed. Since I was introduced to The Republic in high school, the question “What would Plato think?” has always lingered in the background for me on any given topic, whether that be the cultural/political landscape of America in 2020 or the role contemporary education has to play in creating such a landscape.

I’ve always sensed that behind those questions, Plato would ask me about education and its implicit view of human nature and reality. This doesn’t surprise me given that education is at the heart of his tome, The Republic. Knowing this, I opened my copy of the dialogue to glean some insight on how to apply his wisdom to today’s education. But, lo, before I could even begin reading the bust finally spoke, in a whisper, three counsels on education. Pen in hand I took notes as if it were wisdom from above. Here’s the first counsel I could barely make out:

Be a lover

This got me thinking. The education professionals of Socrates’ day were the sophists, those itinerant teachers of the art of rhetoric who claimed that with their techniques one could achieve and know almost anything. As denoted by their name, they claimed to have wisdom (sophia). Now, Socrates, desiring wisdom more than anything else, tested them to see if they indeed possessed her but, as you know, they came up short. One can follow Socrates’ “war and battle” with the Sophists in the Gorgias, which is perhaps my favorite dialogue.

When I taught high school, I always came back to this dialogue when I met professed “professional” teachers who claimed to be able to effectively teach any subject without having really learned the subject from the inside. Ah, yes, some of them had to take an exam on a given subject in order to teach it, but I did not find them having a passion for the subject. Maybe my insecurity in not having an educational degree got the best of me, but I always wanted to hand them a copy of the Gorgias.

The sophists liked to be seen as professionals. Nothing wrong with that, but very often it is a misguided professionalism, in that it is not at the service of reality but often indifferent to it, as Socrates came to show. In an introduction to the Gorgias, famous translator Joe Sachs writes,

We all know that some teachers are better at what they do than others are. But what makes them better? Do they have a technique? Some think they do, and they may even claim to have an expertise in pedagogy. I engaged in teaching for some decades, and opinions were mixed about how well or badly I did at it, but I was always made uneasy when others claimed to have any special pedagogical knowledge. Teaching as distinct from training or instructing, has always seemed to me to be a natural outgrowth of learning. There is no technique for the latter, and the adoption of one for the former undermines its very sources. Learning depends on desire and effort, and those who know learning from the inside, and have kept it alive in themselves, can recognize its beginnings in others in all their unpredictable shapes and try to invite, encourage, and assist them. Pedagogical techniques always seem manipulative to me, as though the learner were some neutral material for the teacher to mold, but anyone who has experienced it knows that learning has to follow its own course and cannot be manipulated. Learning can be coaxed, or stimulated, or inspired, but in such matters one size does not fit all. So the very word “pedagogy” put me on alert for something that is unlikely to be what it claims to be. Now it happens that this analogy is not original with me, but taken from a more complex analogy Socrates makes in the Gorgias.

Teachers must imitate Socrates and his love for wisdom in its various domains and communicate that love to their students in a way that suits them, introducing them to reality and the discipline of attention. Professionalism is cold and detached. Socrates is fiery and passionate, desiring to be immersed in the light of reality. Follow Socrates and not the sophists.

Lo, the second counsel spoken in a whisper:

Bring back the Allegory of the Cave as the Image of Education

I’m a little reticent about this given that The Republic has such a bad reputation these days because of its supposed authoritarianism. But this view of it is superficial. It is Plato’s educational manifesto, which may seem odd given that the dialogue is typically presented as political philosophy. But for Plato, the two go together. Education shapes the way human beings see the world and encourages them in certain ways of life. It is a leading forth to the contemplation of the Good, and politics is the practical fostering of the Good in communities and individual lives. The greatest image of education as such is The Republic’s Allegory of the Cave, for the protagonist is led out of the cave to properly see only to be called back into the cave so as to lead others to the light.

The allegory presents education as a conversion of the whole soul, away from appearance to reality. The journey outside the cave requires askesis (training), accustoming the soul to the light of reality. Education, accordingly, begins with proper vision (contemplation or theoria, seeing). But the seeing is accompanied by doing, and right action is only possible through right vision. The one who beholds the vision of the good must go back down amongst the prisoners. At first, those still imprisoned in the cave will see such a person as a laughingstock because he has lost the capacity to pass judgment on the shadows like the others. His ascent out of the cave is taken as part of his ruin, encouraging others not to make an effort to go up. But after this person adjusts his eyes to the shadows, he can lead people beyond the shadows to behold what is. Such a person is the teacher, the one who helps others adjust their eyes to the light, which ultimately is the Good itself. They are like the doctor who carefully brings her patients back to health. But just as in any adjustment (physical and spiritual), resistance should be expected.

Exhausted, I figured Plato would have mercy on me and be done. But he had one more. Behold, the third counsel:

Expect Resistance

I know this one all too well. Education is hard work for the teacher and the student, and no one likes hard work. But as the placard in the gym says, “No pain, no gain.” Working out well requires a coach who is not only knowledgeable but a living witness that what he is proposing works. The sophists did neither. They pandered to their students, gaining prestige in society by their flattery. As Socrates says, they fed their students pastries, tasty but empty calories. On the other hand, Socrates, like a good doctor, fed his disciples the best foods for the body. Even more, he embodied what he taught. Like Socrates, find whatever is excellent or praiseworthy, and have your students think about these things. Desire these things yourself as a first step to getting your students there. But expect resistance. Like the prisoners in the cave, students and their parents may have to be “dragged out” in the form of homework and projects.

Now, teachers are not sadists but, as I have said before, more like doctors who must speak the truth and help someone make the difficult journey there. Think of your students as Odysseus needing to leave Calypso’s cave, with all its superficial delights, and head home for union with faithful Penelope. Teachers are like Hermes, the messenger, and the Good Shepherd communicating a way beyond the cave and guiding students back home. But it is important to bear in mind what happened to Socrates, a messenger who escaped the cave. He was sentenced to death by the Athenians for “corrupting the youth.” You may not be treated the same way Socrates was but expect some kind of resistance.

For too long American education has gone in a direction far removed from the educational vision of Plato. As we survey the fragmentation and vice in our society today, it might be wise to relearn Plato’s educational vision and put it into practice as best we can. A good place to start is by rereading his great educational dialogues and imitating Socrates as lovers of the beautiful and the good. Also, it wouldn’t hurt to buy a little Plato bust like mine, a good reminder in all things, even in our practice of the faith, to be Platonic. And, who knows, after you’ve soaked in his wisdom in the dialogues, trying to see the world and education as Plato does, perhaps the little bust of Plato on your desk will begin to speak.