During my early morning commute to the office, I usually listen to audiobooks. Currently, I’m listening to a book on what happened on the eastern front during World War II, the major center of the war that is still unfamiliar to most Americans.

But as I listen to the book, I keep thinking about my friend Jerzy who lived through this history.

Years ago, over a great cup of coffee at McDonald’s, Jerzy told me and my fiancée (now my wife) his life story. Cramped around a little table by the cashier, my fiancée and I listened attentively to Jerzy emotionally recount his life, with Kleenex in hand. I was stunned. Stories like Jerzy’s need to be heard, and I was incredibly honored to hear his that night at the McDonald’s on the South Side.

Jerzy and I had been friends since my high school days, when I attended early morning Mass before school. Jerzy was a faithful elderly man known in the parish for his devotion to the Eucharist, and he used to come up to me after Mass to talk. He was concerned about the faith being passed on, and I—not through any merit of my own—became a sign of hope to him. Only later did I learn that throughout his life Jerzy was always on the lookout for signs of hope. He lived through the darkest of times, but he never fell into despair. He knew that no matter the trial there was a greater purpose. Like John Paul II, he is a witness to hope, a hope that gives meaning to our lives.

I stayed in touch with Jerzy during and after my college years. I would talk with him and his wife Paulina after Sunday Mass when I would be in town visiting my family. Jerzy was from Poland, and when I fell in love with a Polish girl I’d met as a grad student in Washington, DC, I was eager to introduce him to her. After a few pleasant meetings, Jerzy wanted to tell us a little more about himself. I’d had no idea how he arrived in America but as it turned out that, like many other Poles during the Second World War, Jerzy’s journey to America was nothing but miraculous.

Jerzy was born on a farm in eastern Poland before World War II. His father was a distinguished soldier who proved himself in the Polish-Soviet War of 1920. As a reward for his courage, the newly founded Polish government gifted him with lands near Wilno, what is now Vilnius, Lithuania. When the Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, his father was called to service on the Polish western front, leaving his family on the farm. Jerzy’s mother had recently delivered her fifth child, a baby boy. At the time, the Poles did not know of Hitler and Stalin’s Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, an agreement to eliminate Poland once again from the map. On September 17, 1939, the Red Army invaded Poland’s eastern half, the beginning of the mass deportation of 1-2 million Poles to Gulags in Siberia. One day, with their father still fighting the Germans on the western front, Jerzy’s family heard a knock on the door. It was the NKVD, saying they had less than twenty minutes to pack their stuff and get on a train.

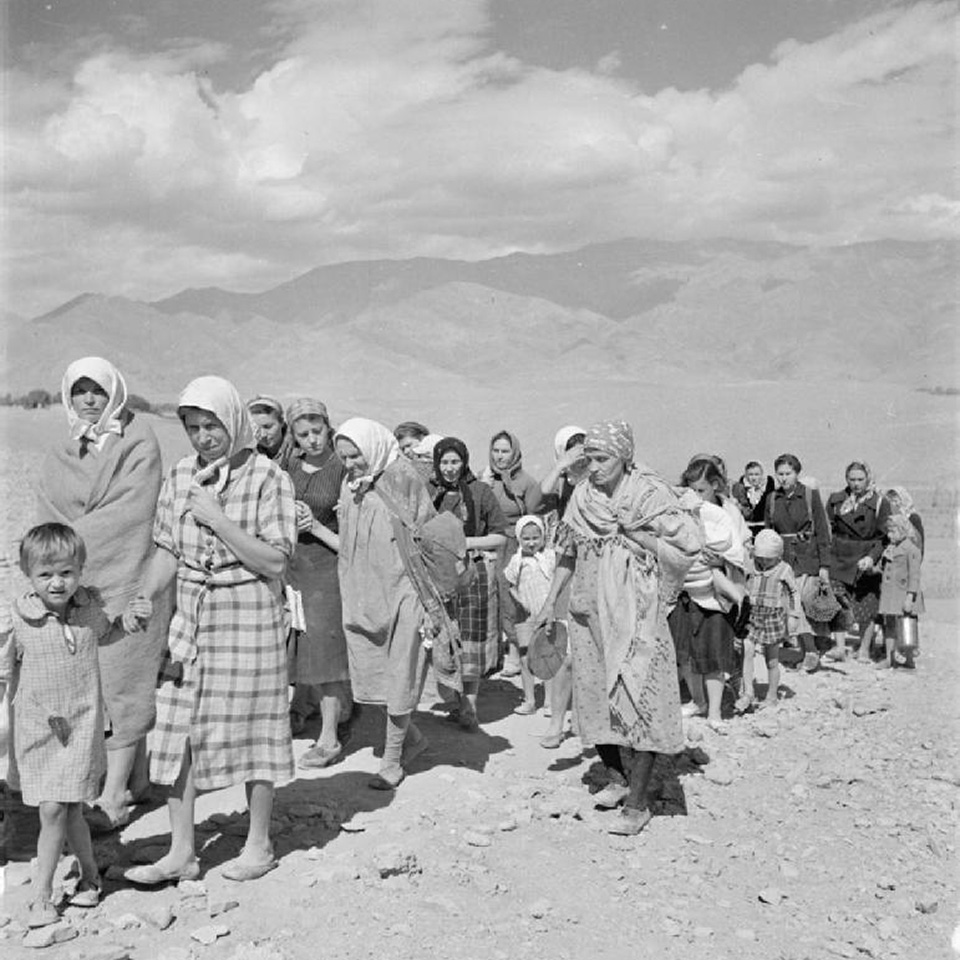

Jerzy and his family were sent to Siberia (possibly Kazakhstan) to work in the Gulags, unsure whether they would survive. The Soviets worked prisoners to the bone and gave little hope of survival.

Conditions in Siberia were brutal. In the winter, freezing to death was likely. And the summers were hellishly hot, with swarming, biting insects that never seemed to quit. Like the times, it was a wasteland, inhospitable to human beings. But the gulag was not the worst part of the story.

Operation Barbarossa (the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941) turned out to be a blessing. It forced Stalin to look for an ally in the West. While Churchill loathed communism and did not want to have an ally in the Soviet Union, he realized that he did not have an option. The Polish government-in-exile was in London, led by Władysław Sikorski. If Stalin wanted to have the United Kingdom as an ally, he needed to concede some things to the Poles. No Pole wanted to be friendly with the enemy—in addition to the mass deportation of Poles, the Soviets not only ensured the elimination of Poland but also executed 22,000 Polish military officers and members of the intelligentsia in the Katyn forest massacre of 1940—but Sikorski had no choice but to sign the Sikorski-Mayski agreement that ensured the release of Poles in Soviet camps, the camps Jerzy was in.

For the Soviets, release meant opening the gates of the camp. They eventually did provide trains, but the conditions were so bad that many people died in them. Jerzy said that was the beginning of a struggle for survival that would take him around the world. No provisions were given; they had to make it on their own. But Jerzy believed God was always in charge, leading him and his family on a trail of miracles.

They had no food. Dehydration was the biggest threat to life, and thousands of evacuees died of dysentery along the way. But Jerzy’s family came upon an abandoned village (likely a village of Volga Germans) that probably was only deserted for a couple of days or even a few hours before they arrived (the Soviets deported many ethnic Germans in Russia to camps in the east in fear of German collaboration with the advancing German army). Jerzy thought it was a miracle. There was water. Fresh food was still available; they were not going to starve.

Eventually reaching the Caspian Sea, the deportees sailed to Iran. It was controlled by the Soviets, so the Poles had to find a way out. Jerzy’s family got on a ship that was supposed to sail for Africa, but was diverted to India. From India, they sailed to New Zealand, eventually landing in Mexico. Jerzy and his family traveled on to Los Angeles and finally settled on the South Side of Chicago.

Jerzy’s youngest brother, an infant at the time of their deportation, eventually became a priest, and Jerzy became well-known for his devotion to Eucharistic Adoration. He was a true pillar of the parish. Before I learned his full story, I had already known there was something admirable about him. Jerzy loved to talk about his encounter with John Paul II during the pope’s historic visit to Chicago in 1979. Like John Paul II, Jerzy was, in a way, brought from Poland, sent around the world, ultimately to land in my parish as a witness to hope. His faith in the Eucharistic Lord had guided him on his earthly pilgrimage, which in many ways reflects the earthly pilgrimage of the Church.

Like Jerzy—like John Paul—the Church is a stranger in a strange land, journeying across the sands of time, looking forward to her arrival at the heavenly Jerusalem. Along the way, she is sustained by the presence of her Lord in the Heavenly Manna, the Eucharist. In the struggle for survival, her faith in the Lord grows, ever mindful that she is walking in the footsteps of the Lord. Persecution cannot destroy the faith in which she lives.

The Poles who were deported and spread throughout the world because of the persecution of the Soviets ended up bringing much good to their newly embraced homelands, and Jerzy stood out to me as a true man of faith. Without his witness I do not know who I would be.

God’s providence is strange and often it seems to be without sense. But when we zoom out and take the long view of things and contemplate the whole pattern of our lives, perhaps we will see the beauty and purpose of it all shine forth. Many of us are worried about handing on the faith to the next generation. But heeding the words of another Pole who survived the war, we should not be afraid but only place our hope in the Lord Jesus Christ. Our lives might not be as adventurous as Jerzy’s, but we should trust that no matter where we go and what hardship we are put through, if we remain in the Lord we will bear much fruit. I hope that what Jerzy handed on to me will be handed on to others. Young generations need to learn the stories of those who preceded them, especially the stories of people like Jerzy. In such people, we see that God never abandons us, but asks us to trust in his protective care, looking, like Jerzy, for signs of hope.