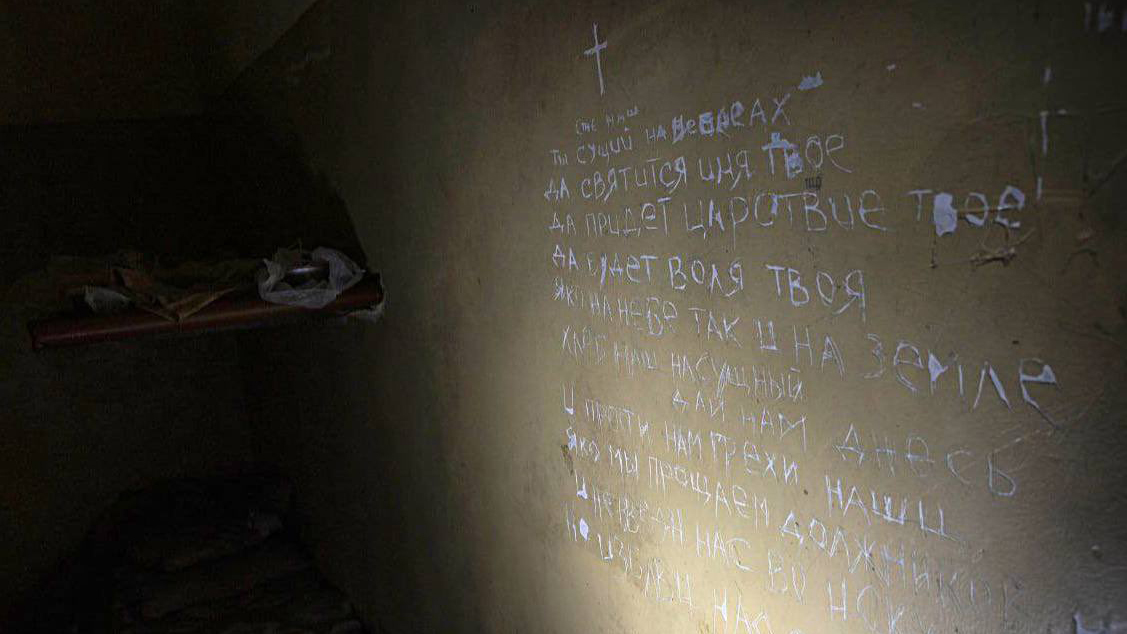

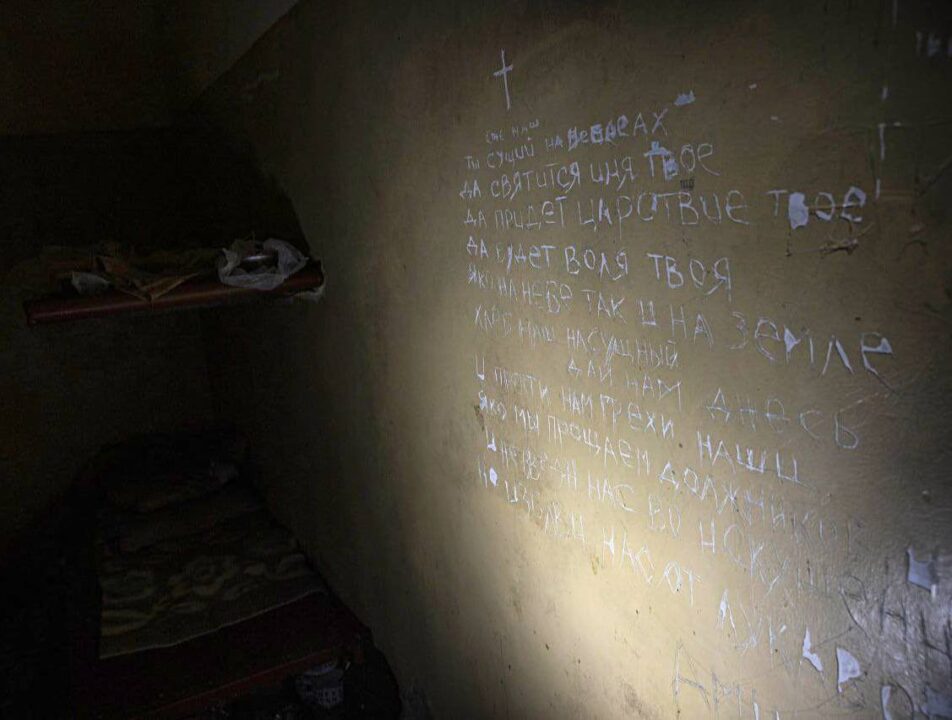

A friend sent me a Twitter post of the “Our Father” found etched in Ukrainian on a wall of a Russian torture dungeon in the Balakliya, Ukraine. Ukrainian troops recently liberated the city of Balakliya from Russian forces, and I am sure that upon seeing the words “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us,” soldiers’ hearts were touched but likely strained due to the seeming injustice of calling upon divine mercy in response to such brutality.

Central and Eastern Europe has a long and intense history of violence, especially during the last century, giving it the name the “Bloodlands” by many historians. It is hard for Americans to fathom the scale of violence and chaos that descended—and continues to descend—upon this land, but it’s even harder to imagine the forgiveness shown by its saints.

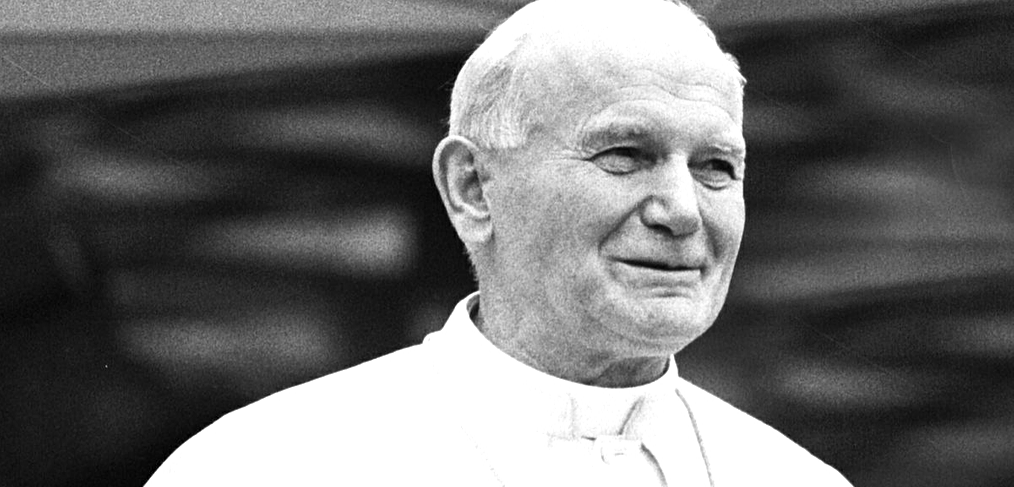

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, a simple, uneducated, young Polish nun, Faustina Kowalska, received visions of Jesus who chose her to be, according to Pope John Paul II, “the great apostle of Divine Mercy in our time.” During her short life, she was not well received. Her fellow sisters thought her mad, refusing to believe her visions. And even her spiritual director, Bl. Michal Sopocko, a trained theologian who taught in Vilnius, at first did not believe her. But eventually, he came around to the truth of her claims. But the message of Divine Mercy was banned by the Vatican in 1959 based on concerns about Faustina’s claims, potential theological error, and association with Polish Patriotism. But that was lifted at the request of the Archbishop of Krakow, Karol Wojtyla (future Pope John Paul II), in 1978. He believed that Faustina’s message was exactly what the world needed to hear in our times.

This summer, I spent most of my time near the Divine Mercy Sanctuary in Krakow where St. Faustina’s tomb is located with the second Divine Mercy Icon. Krakow is not far from Ukraine, and the city continues to host many Ukrainian refugees. My wife and I have traveled to the Divine Mercy Shrine and the gigantic Sanctuary of John Paul II across the field almost every year since the beginning of our marriage, but this year—with the war raging in Ukraine—was the most touching for me. It forced me to attend to the power of the Divine Mercy and its importance for the situation in Ukraine.

Every day at 3PM, the Divine Mercy chaplet is said in five languages. It is as if the whole Church was gathered in this place to offer with Christ through the Holy Spirit and to the Father the plea for mercy, chanting “have mercy on us and on the whole world.”

John Paul II was a committed apostle of the Divine Mercy. As a great historian of Poland and the Slavic peoples (his interviews offer a basic history of Central-Eastern Europe, which come in handy when trying to understand conflicts like the one now in Ukraine), he knew first hand the evils of the twentieth century inflicted on his people in the Second World War and the totalitarian systems of that time. He also knew that divine mercy was the only sufficient way of healing the sins of the world. As Archbishop of Krakow, he took great interest in Faustina’s Gospel of Divine Mercy and worked to popularize it first amongst the Poles and eventually as Pope within the whole Church. He saw it as reiterating the Gospel.

In Memory and Identity, he said, “It was as if Christ had wanted to say through her [Faustina]: ‘Evil does not have the last word!’ The Paschal Mystery confirms that good is ultimately victorious, that life conquers death and that love triumphs over hate” (p. 55). And with today’s war and the rising concerns over a coming world war, the message of the Divine Mercy is more relevant than ever before. We must remember, no matter what comes, that evil does not have the last word! This is why it is so important to pray constantly with the words of the “Our Father” always on our lips.

Like the Icon of the Divine Mercy, the “Our Father” is Christological. It draws us into the One who bore the burdens of us all and triumphs over all hatreds, wars, and tyrants. We cannot forget this today. Forgiveness is only truly possible in Christ. In the words of Reinhold Schneider, “Love has just one form—your Son.” And while the conflict in Ukraine (which in many ways involves the whole world) is very complicated from a geopolitical point of view and in need of a multifaceted response, the only sufficient response is what that Ukrainian prisoner etched on the wall: The “Our Father.” May we do likewise, etching in our hearts the prayer that saves.

Something like this has been done before. Not far from Krakow is the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp where Nazis exterminated mostly Jews and Poles. Edith Stein and St. Maximilian Kolbe were killed there. But evil does not have the last word. It must have been difficult to believe that in Auschwitz, one of humanity’s darkest moments.

The Sacred Heart of Jesus, etched into the wall of Cell 21 down the hall from the cell where Kolbe died is a reminder to unite our hearts to the Lord’s, by Stefan Jasienski, a Polish officer and prisoner of war who eventually died in Auschwitz. In the drawing, a prisoner, likely Stefan himself, embraces Jesus and rests his head on his heart. By doing this, almost through exchange, his heart becomes like the heart of Jesus: full of mercy. In the face of Nazi brutality, I can imagine that when he prayed the “Our Father,” the words “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us” seemed impossible. But by letting his heart become like that of Jesus, all things became possible. And such a possibility remains for us today.