Reflecting on the recently-concluded Year of Saint Joseph, I cannot help but think of the Australian children’s cartoon that captured the hearts of children—and parents—across the world: Bluey.

Originally premiering in October 2018 and now entering its third season overseas, we follow “Bluey, an anthropomorphic six-year-old blue heeler puppy who is characterized by her abundance of energy, imagination, and curiosity of the world. The young dog lives with her father, Bandit; mother, Chilli; and younger sister, Bingo, who regularly joins Bluey on adventures as the pair embark on imaginative play together.”

But this generic Wikipedia description fails to capture what has been so striking about the show since the very first episode: Bluey proudly displays the profound goodness of family life, and is particularly positive in its portrayal of fathers.

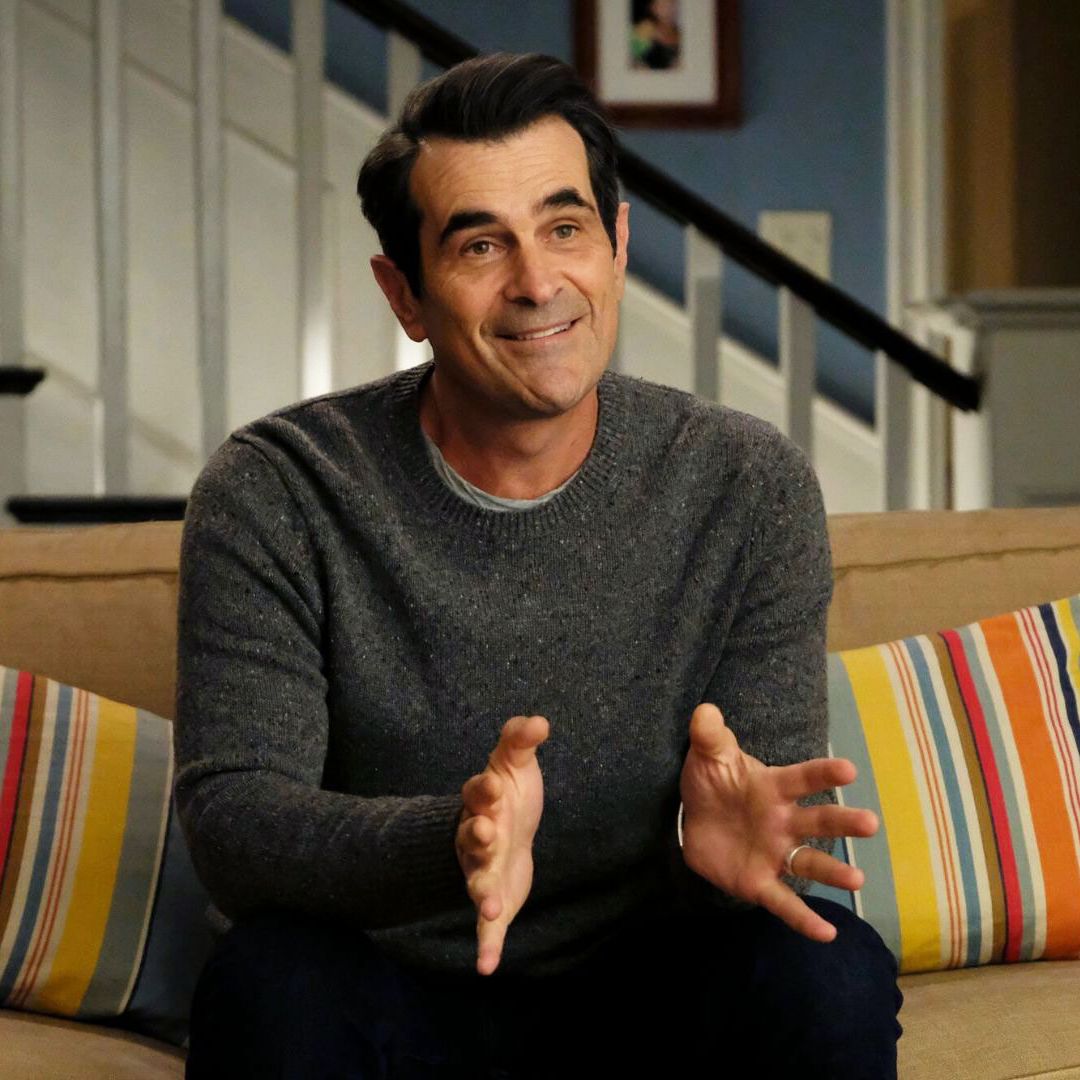

As a husband and father of two children, I loathe pop culture’s comedic crutch of displaying a dad as a goof (Phil Dunphy) or generally terrible (Homer Simpson)—caricatures offered for cheap laughs. Not so with Bandit! While he is not the title character, I would argue that he is the heart of the show. Finally, here is a television series with an awesome, devoted, work-from-home dad, who is spontaneous and happy-go-lucky (which drives many of the storylines and conversations with his daughters). Most importantly, he loves his children dearly, playing endless games with them and teaching them valuable lessons all the while.

Within forty seconds of the very first episode—titled “Magic Xylophone”—we find Bandit tickling Bluey by pretending to play the piano on her belly, much to her shrieking delight. What an incredibly positive note on which to start the entire series! (Let’s also note for the record that Bandit plays Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 11, a particularly mellifluous introduction to classical music for toddlers). The rest of the episode is raucous and hilarious, with Bluey and Bingo fighting each other to freeze Bandit every time they play a note on the xylophone. Eventually, they learn the value of sharing and working together to prank their dad. All it took was seven minutes (the length of each episode), and I was hooked.

In another episode, entitled “Take Away,” Bandit brings the girls along to pick up food only to discover that they have to wait five minutes for the shop to correct his order. He decides to play “Dad Reads the Newspaper” while waiting, but Bluey and Bingo are too curious, playful, and impatient to let that happen. The kids embark on a sequential series of questions, problems, and emergencies (inevitably involving a child needing to go to the bathroom) that require Bandit to literally run back and forth across the screen, ending with him falling to the ground covered in food, groaning with frustration. But then the girls open a fortune cookie, and he reads: “Flowers may bloom again, but a person never has the chance to be young again.” In that moment of clarity, he remembers that the messiness of childhood is a beautiful burden for parents to bear, and he embraces the craziness with laughter.

This echoes Pope Francis’ personal reflections on Saint Joseph, which he released on December 8, 2020, the 150th anniversary of the proclamation of St. Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church, in his apostolic letter Patris Corde, “With a Father’s Heart.” In it, he writes:

Fathers are not born, but made. A man does not become a father simply by bringing a child into the world, but by taking up the responsibility to care for that child. Whenever a man accepts responsibility for the life of another, in some way he becomes a father to that person. . . . Being a father entails introducing children to life and reality. Not holding them back, being overprotective or possessive, but rather making them capable of deciding for themselves, enjoying freedom and exploring new possibilities.

Bandit takes up the mantle of responsibility in every show—and apologizes to his family when he stumbles—so well that he sets a normative example of what modern fathers can be. He is such a profoundly good dad that every episode inspires me to be a better parent. “Magic Xylophone” shows a father who is working hard at play, and that’s a job that I’m struggling to relearn. Nearly every episode has Bandit playing a new game with his kids that I’ve never thought of, and most are now in the rotation with my children. “Take Away” helps me recapture the joy of fatherhood in the midst of meltdowns and double blowouts (my last trip to the grocery store was rough—don’t ask). It might seem like a bold statement, but Bandit helps me be a better father. And I’m not the only one: the popular (and secular) website The Dad says that “Bandit Heeler, [is] the Best TV Dad Ever. For Real Life.”

This hints at the evangelical potential of Bluey. Not only is the show a common touchpoint that cuts across the culture, with parents and children of all stripes aware of and adoring the show, but the goodness on display in it is something we should talk about when trying to build communion with others.

Bishop Barron lauds the “three transcendentals”—the beautiful, the good, and the true—as the primary evangelical paths for spreading Christianity. Bluey is artistically beautiful, and most episodes have a wholesome truth to tell. For me though, it is the goodness presented in the Heeler’s family life that will resonate with so many families, arguably because it is the least subjective of the three. Bishop Barron writes:

John Paul II was the second most powerful evangelist of the twentieth century, but unquestionably the first was a woman who never wrote a major work of theology or apologetics, who never engaged skeptics in public debate, and who never produced a beautiful work of religious art. I’m speaking, of course, of St. Teresa of Kolkata. No one in the last one hundred years propagated the Christian faith more effectively than a simple nun who lived in utter poverty and who dedicated herself to the service of the most neglected people in our society.

Bandit is not a saint; he’s just a regular father living in Brisbane who dedicates himself to being the best dad he can be. That’s something that we can all look up to, and it just might help us evangelize in the twenty-first century. As we look back on the Year of Saint Joseph, I highly encourage you to get tangled up in Bluey.