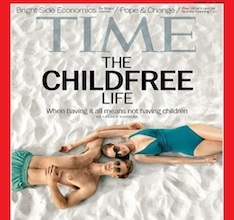

Time Magazine’s recent cover story “The Childfree Life” has generated a good deal of controversy and commentary. The photo that graces the cover of the edition pretty much sums up the argument: a young, fit couple lounge languidly on a beach and gaze up at the camera with blissful smiles—and no child anywhere in sight. What the editors want us to accept is that this scenario is not just increasingly a fact in our country, but that it is morally acceptable as well, a lifestyle choice that some people legitimately make. Whereas in one phase of the feminist movement, “having it all” meant that a woman should be able to both pursue a career and raise a family, now it apparently means a relationship and a career without the crushing encumbrance of annoying, expensive, and demanding children.

There is no question that childlessness is on the rise in the United States. Our birthrate is the lowest in recorded history, surpassing even the crash in reproduction that followed the economic crash of the 1930’s. We have not yet reached the drastic levels found in Europe (in Italy, for example, one in four women never give birth), but childlessness has risen in our country across all ethnic and racial groups, even those that have traditionally put a particular premium on large families. What is behind this phenomenon? The article’s author spoke to a variety of women who had decided not to have children and found a number of different reasons for their decision. Some said that they simply never experienced the desire for children; others said that their careers were so satisfying to them that they couldn’t imagine taking on the responsibility of raising children; still others argued that in an era when bringing up a child costs upward of $250,000, they simply couldn’t afford to have even one baby; and the comedian Margaret Cho admitted, bluntly enough, “Babies scare me more than anything.” A researcher at the London School of Economics weighed in to say that there is a tight correlation between intelligence and childlessness: the smarter you are, it appears, the less likely you are to have children!

In accord with the tenor of our time, those who have opted out of the children game paint themselves, of course, as victims. They are persecuted, they say, by a culture that remains relentlessly baby-obsessed and, in the words of one of the interviewees, “oppressively family-centric.” Patricia O’Laughlin, a Los Angeles-based psychotherapist, specializes in helping women cope with the crushing expectations of a society that expects them to reproduce. As an act of resistance, many childless couples have banded together for mutual support. One such group in Nashville comes together for activities such as “zip-lining, canoeing, and a monthly dinner the foodie couple in the group organizes.” One of their members, Andrea Reynolds, was quoted as saying, “We can do anything we want, so why wouldn’t we?”

What particularly struck me in this article was that none of the people interviewed ever moved outside of the ambit of his or her private desire. Some people, it seems, are into children, and others aren’t, just as some people like baseball and others prefer football. No childless couple would insist that every couple remain childless, and they would expect the same tolerance to be accorded to them from the other side. But never, in these discussions, was reference made to values that present themselves in their sheer objectivity to the subject, values that make a demand on freedom. Rather, the individual will was consistently construed as sovereign and self-disposing.

And this represents a sea change in cultural orientation. Up until very recent times, the decision whether or not to have children would never have been simply “up to the individual.” Rather, the individual choice would have been situated in the context of a whole series of values that properly condition and shape the will: family, neighborhood, society, culture, the human race, nature, and ultimately, God. We can see this so clearly in the initiation rituals of primal peoples and in the formation of young people in practically every culture on the planet until the modern period. Having children was about carrying on the family name and tradition; it was about contributing to the strength and integrity of one’s society; it was about perpetuating the great adventure of the human race; it was a participation in the dynamisms of nature itself. And finally, it was about cooperating with God’s desire that life flourish: “And you, be fruitful and multiply, teem on the earth and multiply in it” (Gen. 9:7). None of this is meant to be crushing to the will, but liberating. When these great values present themselves to our freedom, we are drawn out beyond ourselves and integrated into great realities that expand us and make us more alive.

It is finally with relief and a burst of joy that we realize that our lives are not about us. Traditionally, having children was one of the primary means by which this shift in consciousness took place. That increasingly this liberation is forestalled and that people are finding themselves locked in the cold space of what they sovereignly choose, I find rather sad.