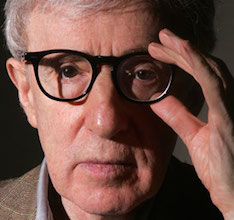

Who would have thought that Woody Allen, who twenty years ago was separating from his longtime girlfriend to notoriously marry her adopted daughter, would emerge as a defender of what can only be called traditional morality? And yet, I find that conclusion unavoidable after viewing the writer-director’s most recent offering, “To Rome With Love.” This film is the latest in a series of Woody Allen movies—“Match Point,” Vicky Christina Barcelona,” “Midnight in Paris”—celebrating great European cities, and it shares with the last of those three a certain whimsical surrealism.

“To Rome With Love” presents a number of story lines, none of which interweave at the narrative level, but all of which share a thematic motif, namely, the need to resist those things that would tempt us away from real love. The funniest and most bizarre of Allen’s tales has to do with a very ordinary man, Leopoldo, played by the wonderful Italian character actor Roberto Benigni, who one day inexplicably finds himself the center of intense media attention. As he makes his way to his car, Leopoldo is mobbed by photographers and reporters peppering him with questions about his breakfast preferences and his favorite shaving cream. Everywhere he goes, he is recognized and lionized. Women suddenly appear, offering themselves for his sexual gratification. When he asks one of his colleagues why this is happening, the answer comes: “You’re famous for being famous.” Now at one level, of course, this is a parody of our “breaking news,” celebrity-obsessed, Kardashian culture. But Allen uses this little fantasy to make another, deeper observation. Though put off by many aspects of his “fame,” Leopoldo also becomes addicted to it. When another very ordinary figure suddenly attracts the media spotlight, Leopoldo, lamenting his lost fame, dances on one foot in the middle of a busy intersection just to get people to notice him once more. At this point, the poor man’s wife intervenes, and Leopoldo realizes that his notoriety, superficial and evanescent, is no match for the affection of his wife and children.

Another farcical tale has to do with Milly and Antonio, a newlywed couple from the Italian countryside who have ventured into Rome for their honeymoon. Looking for a hairdresser, Milly gets hopelessly lost and finds herself on the set of a movie starring one of her favorite actors. In short order, the leading man charms her, romances her and leads her back to his hotel room. But before he can complete his seduction, they are held up at gunpoint by a thief who manages to chase the frightened actor away. Dazzled by his looks and by the “excitement” he represents, Milly then gives in and makes love to the thief. Meanwhile, in a case of mistaken identity, the abandoned Antonio meets Anna, a voluptuous prostitute played by Allen favorite Penelope Cruz. Despite his embarrassment and protestations, Antonio gives in to Anna’s charms and allows himself to be seduced. Covered in shame, Milly and Antonio eventually make their way back to their honeymoon hotel suite and admit to one another that they would like to return to their home in the country and raise a family.

In some ways the most conventional of the stories is the one that features Woody Allen himself as a retired opera producer who has come with his wife to Rome to meet the parents of the young man to whom their daughter is engaged. Allen’s character is utterly bored by his future son-in-law’s parents until he hears the father, Giancarlo, singing—like a combination of Caruso and Pavarotti—in the shower. When he presses the man to share his gift with the wider world, he is met with complete resistance. When Giancarlo gives in and agrees to audition, he fails to impress. Finally, it dawns on the opera impresario that the man can sing well only in the shower. That light bulb having gone off, Allen’s character arranges for him to sing publicly, but in a makeshift shower! Giancarlo gives a triumphant performance in Pagliacci, and it appears as though fame and fortune await. But upon reading the reviews with pleasure, the man refuses to tour and eagerly returns to his ordinary employment (he’s an undertaker) and the embrace of his family.

These various characters confront, in all of their vivid and seductive power, fame, sex, pleasure, and material success. In each case, moreover, the embrace of these things would involve the compromising of some unglamorous but stable and life-giving relationship. Thomas Aquinas said that the happy life is the one that remains centered on love, for love is what God is. Furthermore, he argued that the unhappy life is one that becomes centered on the great substitutes for love, which are wealth, pleasure, power and honor. What I found utterly remarkable about “To Rome With Love” is how its writer and director consistently and energetically insisted that simple love should triumph over glitz, glamor and ephemeral pleasure. I’m entirely aware that Woody Allen’s private life leaves quite a bit to be desired from a moral standpoint, but in regard to the fundamental message of “To Rome With Love,” Aquinas couldn’t have said it better.