The Apocalypse of Robert Hugh Benson

By Rev. Robert Barron

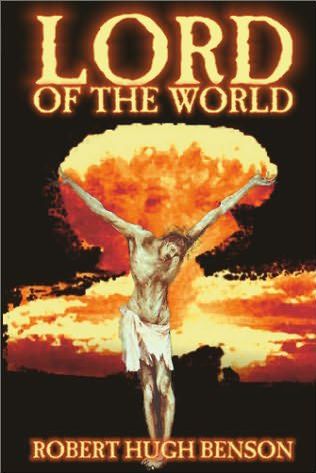

I’ve just finished reading a most extraordinary novel, one that sheds considerable light on the spiritual predicaments of our own time. The odd thing is that it was written just over a hundred years ago. It’s called The Lord of the World, and it was authored by Robert Hugh Benson. Benson was the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and to the shock and chagrin of much of British society, he left the Anglican church and became a Catholic priest. Benson died young at 41, just after finishing this book.

The Lord of the World is an apocalypse. It tells the story of the cataclysmic struggle between a radically secularist society and the one credible alternative to it, namely, the Catholic church. In Benson’s imagined future, Europe and America are dominated by a rationalist regime bent on making life as technologically convenient and politically harmonious as possible. The leaders of this government see the Catholic church, with its stress on the supernatural, on divisive dogma, and on the enduring power of sin, as the principle obstacle to progress. A great messianic figure—Julian Felsenburg—emerges from the heart of the secularist political structure, and he prosecutes a progressively brutal persecution of the church, culminating in the elimination of the Pope, the curia, and most of the bishops of the world. He then establishes an alternative liturgy, predicated upon the worship of an idealized humanity and the rhythms of nature. (In a delicious touch, Benson imagines a former Catholic priest as the master of ceremonies of the new secular liturgy). In the meantime, one surviving Cardinal—an Englishman who bears a striking physical resemblance to Felsenburg—becomes the Pope and takes up his administration of the church in simple quarters in Jesus’ home town of Nazareth. The novel concludes with the climactic struggle between Felsenburg’s secular power and the spiritual power of the church.

Now like any apocalypse, this one is a bit exaggerated and melodramatic; nevertheless, there are a lot of lessons for us in it It is truly impressive that, in 1907, Benson saw, as clearly as he did, the dangerous potential of the secularist ideology. By this I mean the view that this world, perfected and rendered convenient by technology, would ultimately satisfy the deepest longing of the human heart. One of the most elemental truths that the Catholic church preserves is that human beings have been created by and for God and that they will therefore be permanently dissatisfied with anything less than God. In his monumental study of modern society, The Secular Age, the philosopher Charles Taylor speaks of the “disenchanted universe” that has come as a result of the eclipse of religion. This means a world without ultimate meaning or a transcendent reference, a world that speaks only of itself. Benson’s book paints a distressing but realistic picture of people moving about in a disenchanted universe, oscillating between the poles of boredom and fear. One of the most pathetic characters in the novel is Mabel Brand, the wife of a leader of the English political establishment and a woman who once believed in the new secular religion with all her heart. When she saw through its façade to its underlying brutality and inhumanity, she cracked and saw no way out. Like many in her exhausted society, she opted for self-induced and state-sponsored euthanasia. One doesn’t have to be terribly perceptive to appreciate how prophetic all of this has proven to be.

The other truth that Benson grasped was that the Catholic church, with its firm teaching on the reality of the supernatural, is, finally, the single great opponent to this world view. There is a high paradox here. Catholics know that what makes this world fascinating and enticing is precisely the conviction that it is not ultimate, that there is a denser and more permanent world that transcends it. In the light of faith, the things of this ordinary universe, which in themselves would never be enough to satisfy us, become sacraments of an eternal reality. Someone who caught this same paradox was Benson’s contemporary, G.K. Chesterton. Chesterton said that when he was an agnostic and expected to find joy in this world, he was always listless and depressed but that when he found faith, and realized that he was not meant to be fulfilled in this world, he actually became happy and took delight in ordinary things. A younger contemporary of both Chesterton and Benson, Evelyn Waugh, expressed much the same thing when he observed, “for Catholics, the supernatural is the real.”

There are many fights, political, cultural, ethnic, etc. What Robert Hugh Benson saw with extraordinary clarity is that these are all relatively superficial struggles. The final—and finally interesting—battle is metaphysical and religious. It comes down to this question: do we live in an enchanted universe or not? Everything hinges on the way that question is answered.