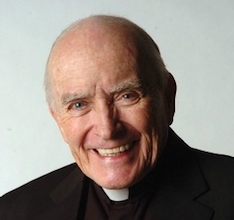

I first met Fr. Andrew Greeley on a cold January day in Chicago in 1988. We were brought together by our mutual friend, Msgr. Bill Quinn, who had been a mentor to Greeley many years before and who had begun to play the same role in my life. Andy walked into the restaurant wearing a beautiful parka with a great hood and carrying loads of his books, which he offered to Bill and me as gifts. I was twenty-eight at the time, and I will confess to being a little star-struck. For the next couple of hours we talked and talked about all sorts of things: the church, of course, but also literature, poetry, sociology, theology, Chicago sports, and politics. As Fr. Greeley talked, his eyes darted back and forth and a little grin always threatened to spread across his face.

Being with him was intoxicating. About a week after this initial meeting, Greeley’s secretary called and invited me to join Andy and Fr. David Tracy, one of the leading Catholic theologians in the world then and now, for lunch at the Quadrangle Club at the University of Chicago. Needless to say, I dropped whatever else I had on my schedule. That summer, and every summer afterward for many years, Andy had and Bill Quinn and me to his home in Grand Beach, Michigan for a wonderful two days of swimming, barbequeing, and endless conversation. One of my enduring memories from those many visits is of Andy sitting in his reading chair, surrounded by mountains of books, articles, and magazines. He read everything and was a man of scintillating intelligence and tremendous range. He was also deeply encouraging to those he believed had promise, and I will remain eternally grateful for his support when I first started my writing career.

I realize that there are some who might wonder at this friendship, given that I tack a bit further to the right on some issues than Andy did. But I think that the characterization of Greeley as a standard issue Catholic liberal is really more of a caricature. Yes, he thought that Humanae vitaewas a mistake, and yes, he thought that women should be allowed access to the priesthood, but I think that if you examine the whole of his thought, you’d see that Andy could perhaps best be described as a conservative Catholic of the golden age of American Catholicism. Andy was a priest, and proud of it. He never appeared publicly without his Roman collar, and he was a passionate advocate of priestly celibacy. He supported Catholic schools, both in his writing and through his extremely generous donations, and he wanted them to carry on the best of the Catholic intellectual and artistic traditions. He loved Dante, Thomas Aquinas, John Henry Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Michelangelo, Mozart, Evelyn Waugh, G.K. Chesterton, and perhaps especially, James Joyce. And what he admired in those figures was what David Tracy called “the analogical imagination” or what might be termed a “sacramental” view of the world. In Andy’s language, this was the distinctively Catholic sense that God “lurked” in all of matter, all of nature, and in the whole of the human drama. This attitude, which was itself grounded in the Incarnation, informed all of Greeley’s writings, from his sociology to his popular theology, to his novels and Blackie Ryan detective stories.

In one of the first articles I ever published, I used the phrase “beige Catholicism” to criticize the culture of the post-conciliar Church in which I came of age. I meant a Catholicism void of color, narrativity, distinctiveness, and edge. Andy loved that phrase and helped to popularize it. He did not want a Catholicism that was a vague echo of the secular culture, and this helps to explain his opposition both to liberation theology (which he thought was more beholden to Marxism than Catholic social teaching) and to radical feminism (which he thought set up a gender war between men and women). He could certainly be a critic of the hierarchy, but he also deeply admired Albert Cardinal Meyer, Pope John XXIII, Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, and perhaps most of all, Francis Cardinal George, with whom he often attended the opera. Once I was privileged to be with Andy at the Cardinal’s table for dinner, just before the two of them left for the opera. As was his custom, Cardinal George commenced the recitation of the Angelus (“The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary…”), and Andy, with eyes closed and hands folded in prayer, joined in. Another quality that he preserved from the Golden Age was a deep devotion to Mary, who appears as a figure in many of his books and novels.

One of Andrew Greeley’s signal accomplishments—and this goes beyond any liberal/conservative split—was his early identification of the problem of clerical sex abuse. Back in the early 1980’s, long before the problem became well known, Andy started blowing the whistle on priests who were abusing children and on the bishops who were ignoring the abuse. I vividly recall the criticism that Andy received for this—“there goes Greeley badmouthing the Church again”—but he was dead right and way ahead of the curve, and the whole church owes him a debt of gratitude.

We did not agree on everything. Perhaps our greatest disagreement had to do with what I took to be Andy’s completely uncritical embrace of the Democratic Party. I used to kid him that if the Democrats ran Attila the Hun for mayor of Chicago, Andy would have voted for him! Those of us who came of age after Roe v. Wade had a considerably more skeptical attitude toward the party of the left. I also felt that Andy didn’t take with adequate seriousness some of the very real negative consequences of the sexual revolution, many of which were accurately prophesied in the much-smaligned Humanae vitae.

But the points of divergence were far less important than the points of contact between us. Andy was a good man, a devoted priest, and a loyal friend. I will miss him. Many times, he spoke of heaven as the “many-colored land.” I pray that he might be, even now, a denizen of that place.