“District 9” and the Biblical Attitude Toward the Other

by Rev. Robert Barron / from America The National Catholic Weekly

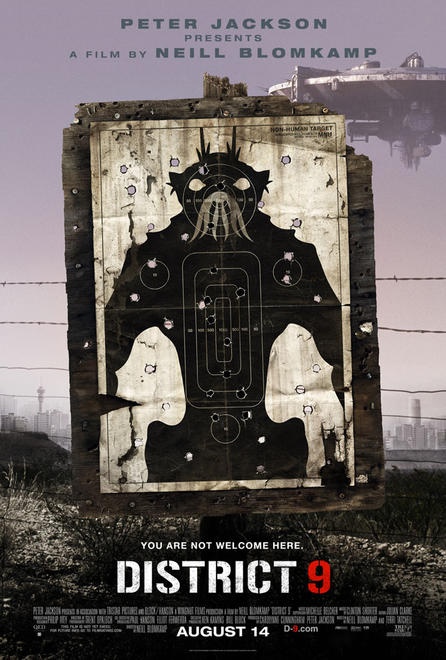

I just saw a remarkable film called “District 9.” It’s an exciting, science-fiction adventure movie, but it is much more than that. In fact, it explores, with great perceptiveness, a problem that has preoccupied modern philosophers from Hegel to Levinas, the puzzle of how to relate to “the other.” “District 9” sets up the question in the most dramatic way possible, for its plot centers around the relationship between human beings and aliens from outer space who have stumbled their way onto planet earth. As the film gets underway, we learn that, in the 1980’s a great interstellar space craft appeared and hovered over Johannesburg South Africa. When the craft was boarded, hundreds of thousands of weak and malnourished aliens were discovered. These creatures, resembling a cross between insects and apes, were herded into a great concentration camp near the city where they were allowed to live in squalor and neglect for twenty some years. In time, the citizens of Johannesburg came to find the aliens annoying and dangerous, and the central narrative of the movie commences with the attempt to shut down the camp and relocate the “prawns” to a site far removed from the city.

I just saw a remarkable film called “District 9.” It’s an exciting, science-fiction adventure movie, but it is much more than that. In fact, it explores, with great perceptiveness, a problem that has preoccupied modern philosophers from Hegel to Levinas, the puzzle of how to relate to “the other.” “District 9” sets up the question in the most dramatic way possible, for its plot centers around the relationship between human beings and aliens from outer space who have stumbled their way onto planet earth. As the film gets underway, we learn that, in the 1980’s a great interstellar space craft appeared and hovered over Johannesburg South Africa. When the craft was boarded, hundreds of thousands of weak and malnourished aliens were discovered. These creatures, resembling a cross between insects and apes, were herded into a great concentration camp near the city where they were allowed to live in squalor and neglect for twenty some years. In time, the citizens of Johannesburg came to find the aliens annoying and dangerous, and the central narrative of the movie commences with the attempt to shut down the camp and relocate the “prawns” to a site far removed from the city.

Placed in charge of the relocation operation is Wikus van de Merwe, an agreeable, harmless cog in the state machine. While searching for weapons in the hovel of one of the aliens, Wikus comes across a mysterious cylinder. When he examines it, a black fluid sprays out onto his face, and in a matter of hours, he is desperately ill. He is taken to the hospital, and the doctors who examine him are flabbergasted to discover that his forearm has morphed into the appendage of an alien. Almost immediately, the state officials reduce the suffering man to an object, resolving to dissect him and experiment on him. Wikus manages a miraculous escape, but he is, throughout the film ruthlessly hunted down. I promise not to give away much more of the plot. I’ll add only this: as his transformation progresses, Wikus becomes an ally of the “prawns” and they come to respect him and to protect him from his persecutors.

With this sketch of the story in mind, I should like to return now to the two worthies I mentioned at the outset. The nineteenth century German philosopher Hegel taught that much of human history can be understood as the working out of what he called the “master/slave” relationship. Typically, people in power—politically, culturally, militarily—find a weaker, more vulnerable “other” whom they then proceed to manipulate, dominate, exclude, and scapegoat. Masters need slaves and slaves, Hegel saw, in their own way need masters, each group conditioning the other in a dysfunctional manner. Masters don’t try to understand slaves (think of the dominant Greeks who characterized any foreigners as barbarians, since all they said was “bar-bar”); instead, they use them. Furthermore, almost all of history is told from the standpoint of the masters, and mastery is the state to which all sane people aspire.

Emmanuel Levinas, a twentieth century Jewish philosopher whose family was killed in the Holocaust, reminded us how the Bible consistently undermines this master/slave dynamic, since it recounts history from the standpoint of the other, the outsider, the oppressed. Levinas argued that Biblical ethics commences, not with philosophical abstractions about the good life, but with the challenging face of the suffering “other.” The prophets of Israel consistently remind the people that since they too were once slaves in Egypt, they must be compassionate toward the alien, the stranger, the widow and the orphan. In the faces of those “others,” they find the ground for their own moral commitments. They compelled the people, in short, not to adopt the attitude of the master but to move sensitively into the attitude of the slave. This unique Israelite perspective came to embodied expression in Jesus, who “though he was in the form of God, did not deem equality with God a thing to be grasped” and who rather “emptied himself and took the form of a slave.” In Christ, the God of Israel became himself a slave, the despised other, even to the point of enduring the rejection of the masters and dying the terrible death of the cross. In Jesus, the God of Israel looks out from the face of the other and draws forth compassion from those who gaze upon him.

In “District 9,” we see the master/slave dynamic on clear display: the characterization of the aliens by a derogatory nickname, their sequestration in a squalid ghetto, the violence—direct and indirect—visited on them consistently, etc. These are practices evident from ancient times to the present day. But we see something else as well: an identification of the oppressor with the oppressed, the openness to interpreting the world from the underside, from the perspective of the victim. This, I would submit, is the Biblical difference, though I doubt that most people today would recognize it as such. It is the view that comes from that strange spiritual tradition which culminates in a God who doesn’t make slaves but rather becomes one.