I’m in the process of re-reading a spiritual classic from the Russian Orthodox tradition: The Way of a Pilgrim. This little text, whose author is unknown to us, concerns a man from mid-nineteenth century Russia who found himself deeply puzzled by St. Paul’s comment in first Thessalonians that we should “pray unceasingly.” How, he wondered, amidst all of the demands of life, is this even possible? How could the Apostle command something so patently absurd?

His botheration led him, finally, to a monastery and a conversation with an elderly spiritual teacher who revealed the secret. He taught the man the simple prayer that stands at the heart of the Eastern Christian mystical tradition, the so-called “Jesus prayer.” “As you breathe in,” he told him, say, ‘Lord Jesus Christ,’ and as you breathe out, say, ‘Have mercy on me.’” When the searcher looked at him with some puzzlement, the elder instructed him to go back to his room and pray these words a thousand times. When the younger man returned and announced his successful completion of the task, he was told, “Now go pray it ten thousand times!” This was the manner in which the spiritual master was placing this prayer on the student’s lips so that it might enter his heart and into the rhythm of his breathing in and out, and finally become so second nature to him that he was, consciously or unconsciously, praying it all the time, indeed praying just as St. Paul had instructed the Thessalonians.

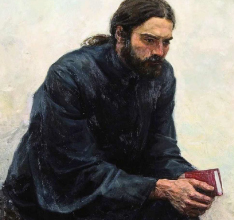

In the power of the Spirit, the young man then set out to wander through the Russian forests and plains, the Jesus prayer perpetually on his lips. The only object of value that he had in his rucksack was the Bible, and with the last two rubles in his possession, he purchased a beat-up copy of the Philokalia, a collection of prayers and sayings from the Eastern Orthodox tradition. Sleeping outdoors, fending largely for himself, relying occasionally on the kindness of strangers, reading his books and praying his prayer, he made his way. One day, two deserters from the Russian army accosted him on the road, beat him unconscious and stole his two treasures. When he came around and discovered his loss, the man was devastated and wept openly: how could he go on without food for his soul? Through a fortuitous set of circumstances, he managed to recover his lost possessions, and when he had them once again, he hugged them to his chest, gripping them so hard that his fingers practically locked in place around them.

I would invite you to stay with that image for a moment. We see a man with no wealth, no power, no influence in society, no fame to speak of, practically no physical possessions—but clinging with all of him might and with fierce protectiveness to two things whose sole purpose is to feed his soul. Here’s my question for you: What would you cling to in such a way? What precisely is it, the loss of which would produce in you a kind of panic? What would make you cry, once you realized that you no longer had it? And to make the questions more pointed, let’s assume that you were on a desert island or that you, like the Russian pilgrim, had no resources to go out and buy a replacement. Would it be your car? Your home? Your golf clubs? Your computer? To be honest, I think for me it might be my iPhone. If suddenly I lost my ability to make a call, my contacts, my music, my GPS, my maps, my email, etc., I would panic—and I would probably cry for sheer joy once I had the phone back, and my fingers would close around it like a claw. What makes this confession more than a little troubling is that, ten years ago, I didn’t even own a cell phone. I lived my life perfectly well without it, and if you had told me then that I would never have one, it wouldn’t have bothered me a bit.

What I particularly love about the Pilgrim is that he was preoccupied, not about any of the passing, evanescent goods of the world, but rather about prayer, about a sustained contact with the eternal God. He didn’t care about the things that obsess most of us most of the time: money, power, fame, success. And the only possessions that concerned him were those simple books that fed his relationship to God. Or to turn it around, he wasn’t frightened by the loss of any finite good; but he was frightened to death at the prospect of losing his contact with the living God.

So what would you cling to like a desperate animal? What loss would you fear? What do you ultimately love?