Joseph T. Stuart, PhD, is Associate Professor of History and Fellow in Catholic Studies at the University of Mary in Bismarck, North Dakota. He is the author of Rethinking the Enlightenment: Faith in the Age of Reason. In this interview, Jared Zimmerer discusses Dr. Stuart’s work and how we might better understand what the Enlightenment caused and what Catholics can learn from its history.

JZ: Did the Enlightenment secularize the modern world?

JZ: Did the Enlightenment secularize the modern world?

JS: This is a complex and fascinating question! Due to the anti-Christian legacy of the French Revolution (1789-1799) many people have assumed the answer is yes. Both Christians and secularists have blamed (or praised) the Enlightenment for this. Christianity just could not stand up, they seem to think, to the critical intelligence of the Age of Reason and the widespread excitement about scientific knowledge.

Social scientists and historians have shown, however, that this is largely a myth. If “enlightenment” automatically led to the loss of religion, then one would expect to find the highest rates of churchgoing among uneducated people today. But that is not the case. Even in the eighteenth-century itself, a major religious revival in the English-speaking world made the later decades in some ways more religious than the early 1700s—even as the Enlightenment spread further.

In addition, some forms of “secularization” are actually fortuitous developments, even from a Christian point of view. Pope Benedict XVI spoke of a “positive secularity.” If “secular” means “the world,” then understanding God’s world on its own terms is important. The papal physician Giovanni Lancisi (1654-1720), for example, mentioned the soul only briefly in his great work On Sudden Deaths and then as being beyond the scope of a physician’s research field. In other words, Lancisi sought to explain only the material causes of medical conditions on their own terms. He did this under the protection of three popes. By undermining superstition, magical thinking, fake miracles, and quack medicine, Enlightenment rationality helped purify faith and supported the rationalization of canonization procedures in Pope Benedict XIV’s Beatification and Canonization of the Servants of God (1734-1738).

Reason is not a negative force or an enemy to faith. Attacking the Enlightenment too much as the cause of modern secularism is a simplification that casts doubt over Christian commitment to the serious intellectual work needed today in the context of modern ideas and methods. Some religious people are okay with that doubt. I am not one of them.

How did Christians utilize the three strategies of conflict, engagement, and retreat in their relationship to Enlightenment culture?

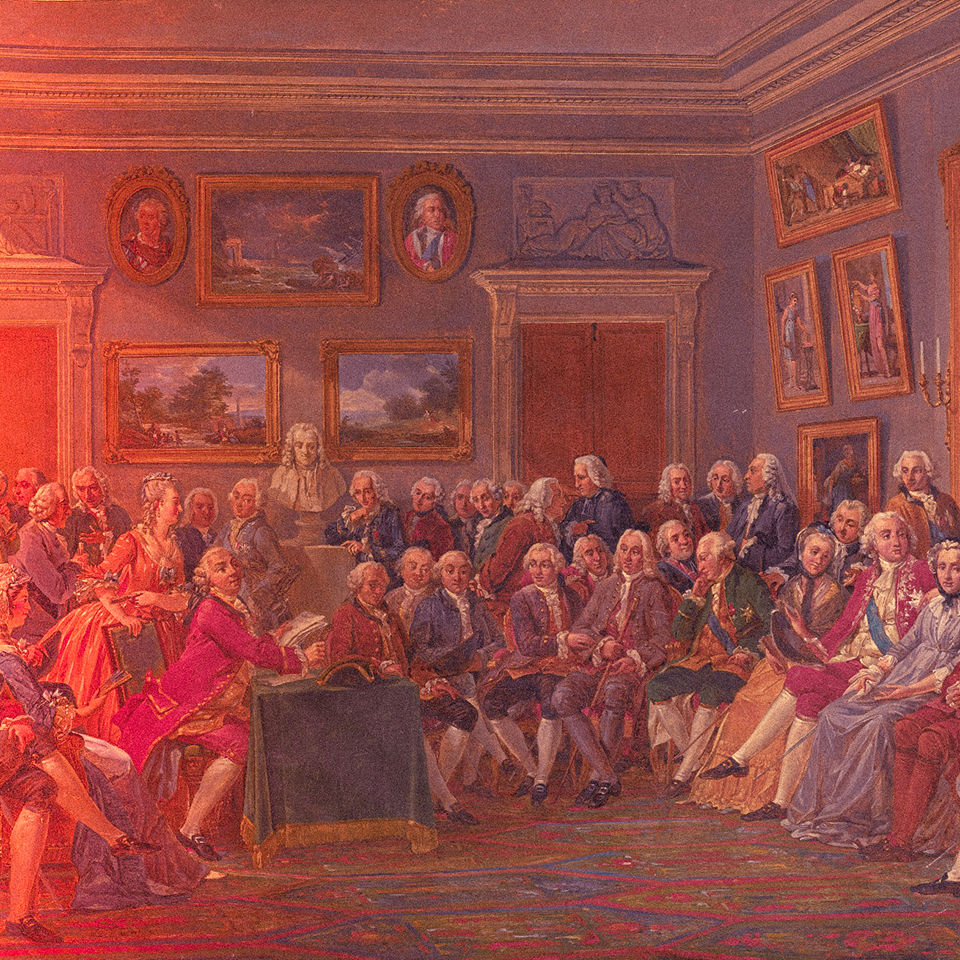

Because the Enlightenment is often ignored as a source of religious inspiration, it needs to be remembered differently. Despite creating serious challenges and direct attacks on faith, especially in France, the Enlightenment also opened new avenues for faith to flourish—Christian faith in particular. That paradox is the subject of my book Rethinking the Enlightenment: Faith in the Age of Reason (Sophia, 2020).

I argue that from a Christian point of view, we need to look at the Enlightenment in three “modes.” This is because Christians interacted with it in three ways during the eighteenth century: through conflict, engagement, and retreat.

(1) Conflict. The “Conflictual Enlightenment” was centered in France and collided with basic Christian beliefs about divine revelation and human nature. It resulted in conflict, confrontation, and even martyrdom, as in the fate of the Carmelites of Compiègne in 1794. The sins of Catholics, however, and their own internal conflicts, proved as dangerous to Catholics as the attacks of famous writers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire.

(2) Engage. The “Catholic Enlightenment,” based in Italy and Germany, sought to embrace human reason as a powerful tool for reforming the Church and society. It elicited an optimistic strategy of sophisticated cultural engagement, as in the work of mathematician Maria Agnesi, Pope Benedict XIV (the “Enlightenment Pope”), and certain Benedictines whose monastic tradition opened them up to various Enlightenment ideas and methods.

(3) Retreat. The “Practical Enlightenment” in the English-speaking world involved the practical people who profoundly shaped modern history through innovations in industry, business, and politics. Amid this new material world, the Christian strategy of retreat (in a spiritual sense) was not one of direct conflict or engagement. It had a different emphasis: to build up the household of faith from within Christian culture and to reach out to others in the “new evangelization” of the day. This movement utilized certain achievements of the Practical Enlightenment, such as mass publishing and better roads, to touch the hearts of thousands with the Gospel.

The three Christian strategies of conflict, engagement, and retreat involved various emphases, strengths, and weaknesses. Christians discerned the need for each depending on their circumstances. When different parts of the kingdom of God work together according to diverse vocations and talents, the relationship between faith and reason rests on a solid foundation. This happened in the Age of the Enlightenment, which has, I think, important implications for our times.

How did the Enlightenment help Christians clarify their own traditions and freedoms?

The historian and Catholic priest Ludovico Muratori wrote the widely respected Science of Rational Devotion in 1747. He was an Enlightener who believed faith and reason need to purify each other—just as Pope Benedict XVI held in his Address in Westminster Hall in 2010. Muratori thought the mind important for holiness in correcting one’s vices and regulating one’s affections. Rational devotion helps one practice restraint and moderation.

The priorities of Enlightenment culture also helped Christians gain greater appreciation for the female mind. In fact, the best place to be a smart woman in the eighteenth century may have been the Papal States, where Pope Benedict XIV promoted women’s careers, such as that of Maria Agnesi (mathematics), Laura Bassi (physics), and Anna Morandi (anatomy). He grew furious when a friar attacked Bassi in public by trying to use the Bible to prove female mental inferiority. The Catholic Enlightenment helped remove some of the misogyny in the way the Bible was commonly read at the time.

In addition, Enlightenment culture helped Christians reconnect to their ancient tradition of freedom of religion. This meant freedom for Catholics, too, as the first bishop of the United States, John Carroll, recognized in the late 1700s. The Second Vatican Council document Dignitatis Humanae held that religious freedom “has to do with immunity from coercion in civil society” and left “untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men and societies toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ.” The roots of this balanced statement can be traced not only to thinkers like Tertullian in the early Church but also to the positive experience of greater distinction between Church and state established in the Enlightenment.

What did the “new evangelization” look like in the 18th century?

It changed the course of the age. Emerging out of the Christian retreat strategy, there was an outward explosion of evangelical (missionary) energy to “renew the spirit of Christianity among Christians” and beyond. This was how the great evangelist St. Louis de Montfort (1673-1716) defined the “new evangelization” of the time. The Company of Mary he founded in 1705 renewed popular religion in western France to such a degree that much of the region rose in rebellion against the anti-Catholic pretensions of the French Revolution.

In the English-speaking world, John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield employed mobility, preaching, publishing, hymns (like “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today,” 1739), and religious societies to ignite a religious wildfire. Their Methodism was not an independent denomination in the eighteenth century but an interdenominational evangelical movement emerging out of the Church of England. It emphasized the possibility of salvation for all people, the experience of the Holy Spirit, and the importance of works of mercy. The three friends were so successful that revival spilled over into the Great Awakening (1740s-1750s) in the American colonies and eventually gave birth to the charismatic renewal and Pentecostalism that now affect the lives of five hundred million people globally. The Wesleys and Whitefield changed the shape of the Enlightenment by altering fundamental cultural assumptions about political authority in the United States and human dignity in the British campaign against African slavery.

What do you hope readers, Catholic and non-Catholic, learn from reading this book?

I hope people will “rethink the Enlightenment” to reflect on their stance toward the modern world. If we hate the modern world, then that affects our attitudes toward everything from politics to technology and relationships. If we love it too much, however, that also affects those things.

As in the eighteenth century, I think there is a need for at least three different strategies in our relation to the modern world. Conflict, engagement, and retreat represent different intentions and even vocations. They all seek to live out the relationship between religion and culture and between personal faith and public life. Carefully integrating even two of the strategies could make for a more effective and psychologically sound relationship between religion and culture. When different parts of the kingdom of God pursue all three of them, however, a strong, intellectually sophisticated, and evangelically oriented Christianity can emerge—as it did in the Age of the Enlightenment.