Beaches, alligators, oranges, Disney. These are some of the first words that come to mind when someone says, “Florida.” For most of us, our knowledge of the Sunshine State’s history is pretty shabby before the year 1970 when air conditioning and Mickey Mouse made living conditions a little more attractive. What few people know, however, is that the state of Florida has been baptized in the blood of martyrs, and before theme parks were built or hotels erected, there stood the cross of Christ on the shores of this state; a cross that would herald the coming sacrifice of its peoples for the sake of the Gospel in our country.

The fifteenth to eighteenth centuries witnessed one of the most prolific and far-reaching expansions of civilization in world history. What began in the late 1400s as a harrowing conquest into the uncharted waters of the West Atlantic reached a staggering peak by 1700, resulting in the rapid colonization of the New World. Between the Spanish and British empires, interspersed with the occasional French or Portuguese excursion, the American continents became European frontiers heralding promises of wealth and fortune.

The Kingdom of Spain was particularly successful in these decades, claiming territories throughout the Western Hemisphere with a special interest in the Caribbean Islands, Mexico, and the Americas. Unfortunately, these times in Spanish antiquity have become synonymous with the violent and corrupt actions of the infamous conquistadors. Every high school student who takes an introductory world history class is bound to study the not-so-benevolent activities of Columbus’ landing in Hispaniola or Cortez’s conquest of Mexico. What is worse, students are led to believe this cruelty was the modus operandi of the Spanish empire. Yet the truth is quite the opposite. Contrary to the revised histories proliferated throughout our educational systems by Prentice Hall or Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the real story of Spanish evangelization (not colonization) is among one of the greatest stories of human rights and Christian endeavor in Western civilization. The best example of this fact is found a lot closer to home than many know.

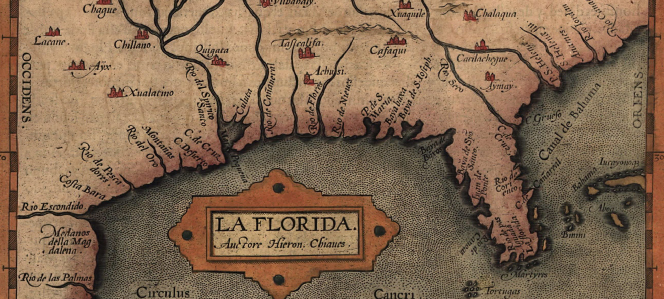

Located between the mighty Aztec pyramids of Mexico and the bustling trade ports of the Caribbean Islands sat a harsh and rugged swamp-land edged by endless beaches. After more than five major attempts at permanent colonization throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, this peninsula finally began to yield promises of a possible viability and long-term settlement. Plagued by scorching summers, poor soil, countless mosquitos, and dangerous wildlife, the name first coined for this landmass seemed ironic, albeit in the years to come, it would prove prophetic: La Florida, “The Land of Paschal Flowers.”

There is so much that can be said about Florida. Truly, its story is one of the most fascinating in American history. It is the first place the Eucharist was offered in the United States. September 8, 1565 saw the founding of what would become America’s first city, St. Augustine. This was followed by the immediate establishment of a mission chain pre-dating those of California by over a century. The purpose of these missions, called doctrinas meaning “a place of teaching,” was to teach Catholicism to local Apalachee-Timucuan tribes.

A special selflessness characterized the Florida evangelizers. Economic prospects in the region were sub-par compared to the inherent wealth of the territories of Central and South America. But this did not prevent Spanish explorers and even the King of Spain himself from investing copious amounts of funds into the development of the Florida mission chain.

Even the great conquistador Pedro Menendez proved a genuine missionary. In a letter written just nine days before his death in 1574, the admiral expressed a touching dying wish:

After the salvation of my soul, there is nothing I desire more than to spend my days in La Florida working for the salvation of souls!

Numerous first-hand accounts reveal that the impetus behind the founding of Florida was not simply a political or economic colonization, but rather a legitimate desire for evangelization. By the mid-seventeenth century, tens of thousands of Native Americans populated the Apalachee-Timucuan missions throughout the Florida Panhandle. And no…these men and women were not forcefully baptized or mercilessly threatened by the fires of eternal damnation. On the contrary, the Apalachee-Timucuan tribes had been slowly converted over many decades by the gentle-hearted and deeply pious example of European priests, some of whom were killed for the sake of the Gospel. This holy method of evangelization was in direct obedience to the papal bull Sublimus Deus, promulgated in 1537 by Pope Paul III, which asserted that “Indians and other peoples should be converted to the faith of Jesus Christ by preaching the word of God and by the example of good and holy living.” Coincidently, this same document condemns those among the Europeans who believe “that the Indians of the West and the South, and other people of whom We have recent knowledge should be treated as dumb brutes created for our service.” In fact, the pope declares, these Native American men and women “are not only capable of understanding the Catholic faith but…desire exceedingly to receive it.”

These final words of Pope Paul III could not be truer. The Native Americans of Florida deeply loved their Catholic faith. Fr. Francisco Pareja, a Franciscan priest of the Florida missions, illustrates just how profound this devotion was in a letter dated from 1616:

Many persons are found, men and women, who confess and who receive [Holy Communion] with tears, and who show up advantageously with many Spaniards. And I shall make bold to say…that with regard to the mysteries of the faith, many of them [the Native Americans] answer better than the Spaniards because the latter are careless in these matters.

In a report filed after his apostolic visitation to Florida in 1633, Bishop Calderon of Santiago de Cuba documents administering the sacrament of confirmation to more than 13,152 Native Americans and Spaniards in less than eleven months. When asked about the status of the missions and its Native American converts, the bishop reported the following to the royal court of Spain:

As to their [the Native Americans’] religion, they are not idolaters and they embrace with devotion the mysteries of our holy Faith. They attend Mass with regularity…and before entering the church each one brings to the house of the priest a log of wood as a contribution…They are devoted to the Virgin, and on Saturdays they attend church when her Mass is sung. On Sundays, they attend the Rosary and the Salvein the afternoon. They celebrate with rejoicing and devotion the Birth of Our Lord, all attending the midnight Mass with offerings of loaves, eggs and other food. They subject themselves to extraordinary penances during Holy Week and during the twenty-four hours of Holy Thursday and [Good] Friday…they attend standing, praying the Rosary in complete silence—twenty-four men, twenty-four women and twenty-four children—with hourly changes. The children, both male and female, got to church [on] workdays, [and] to a religious school where they are taught by a teacher whom they call the Athequi [interpreter] of the church—[a person] whom the priests have for this service.

Spanish and Native American communities lived harmoniously with no form of segregation. All Native American cultural practices that did not prove immoral or sinful were not only allowed, but respected by the Spanish residents. This was especially true in the territory of Florida where prayers such as the Our Father were taught in Latin as well as translated into the local Timucuan dialects. A bilingual Spanish-Timucuan catechism was also created and used to great success.

By the year 1675, the territory of La Florida was enjoying a golden age of peace. The missions were not only stable but growing at a mind-boggling pace. The Native Americans were hungry for the faith and eager to spread the Gospel among their fellow tribes throughout the Florida peninsula. All the efforts and resources invested into the “Land of Paschal Flowers” over a 180 year period bore rich food for the harvest of salvation. But there was a dark cloud on the horizon. Soon, these men, women, and children would have their faith tested, and many of them would lose their lives in what would become the greatest sacrifice for the Catholic faith in American history. In our next article, we will enter into detail about the specific stories of several of these Native Americans and priests who would shed their blood for the name of Christ in Florida.