Prior to Sunday, January 26, 2020, the most famous Catholic on Earth was a Black Catholic.

Excluding the Holy Father, there is little doubt concerning the accuracy of this claim concerning one Kobe Bean Bryant.

Yet the thought has probably never crossed your mind. Why?

This is the great conundrum of Black Catholics: they are at once one of the least familiar and yet most long-standing Christian groups in the United States. They are everywhere and apparently nowhere all at the same time. They are a demographic of uncommon faithfulness, forgotten legacies, and hidden figures.

During and after my relatively short journey into the Catholic Church last year, I have experienced within Black Catholicism this peculiar sort of contradiction at almost every level. This journey began primarily as a theological question (“What is Catholicism?”), but I eventually realized that bound up in that question is the issue of history and identity (“Who is Catholicism?”).

The latter question is one that I think we don’t ask ourselves enough, perhaps especially in America and the larger Western world. But it is within the crucible of this particular part of the world that Black Catholicism was energized, expanded, and exported from its multifaceted African roots.

One of the earliest Christian communities outside of the Roman Empire was in Africa. If you’re thinking of Ethiopia, you’re proving my point. The earliest Christian community in Africa was actually in Nubia (today Sudan) and produced a number of empires lasting well into the late Middle Ages, after which, “because of the wars of the Moors, they could not get another [bishop], and they lost all their clergy and their Christianity and thus the Christian faith was forgotten.”

This history struck me like a brick when I first read about it in Cyprian Davis’ seminal History of Black Catholics. I was dumbfounded not only at the fact that Christianity existed so early in Sub-Saharan Africa outside of Ethiopia, but also at the sheer confidence behind my poorly informed assumptions to the contrary. I knew next to nothing about African Christian history and yet thought I knew it all. And it is exactly this kind of thinking—or lack thereof—that plagues Catholicism today.

As I researched and considered the topic of Catholic history and identity more and more, it became clear to me that Catholicism intersects with my culture in ways I never thought possible, not just on an ancient historical level but also at the level of American history, unique and expressive Black worship, and even my own ancestry. Beforehand, when I had come to terms only with the Church’s theology, I was under the impression that I had to give up the Black Church in exchange for God’s Church. Thankfully I was horribly wrong.

I slowly realized that there’s more to Catholicism than the predominant suburban American expression in 2020, and soon the meaning of the word “Catholic” took on a new meaning—its original meaning. Because the Church is all-encompassing, it is natural for it to include and foster a Black Catholicism.

Within Black Catholicism you might find a number of things the average Catholic has never seen in a Mass before and/or totally disdains: long homilies, a five-minute sign of peace (replete with hugs, kisses, and conversations), gospel choirs, consecration hand drums, drumkits, and entire bands including—wait for it—guitars. Maybe even two of them. Bass and electric only, though.

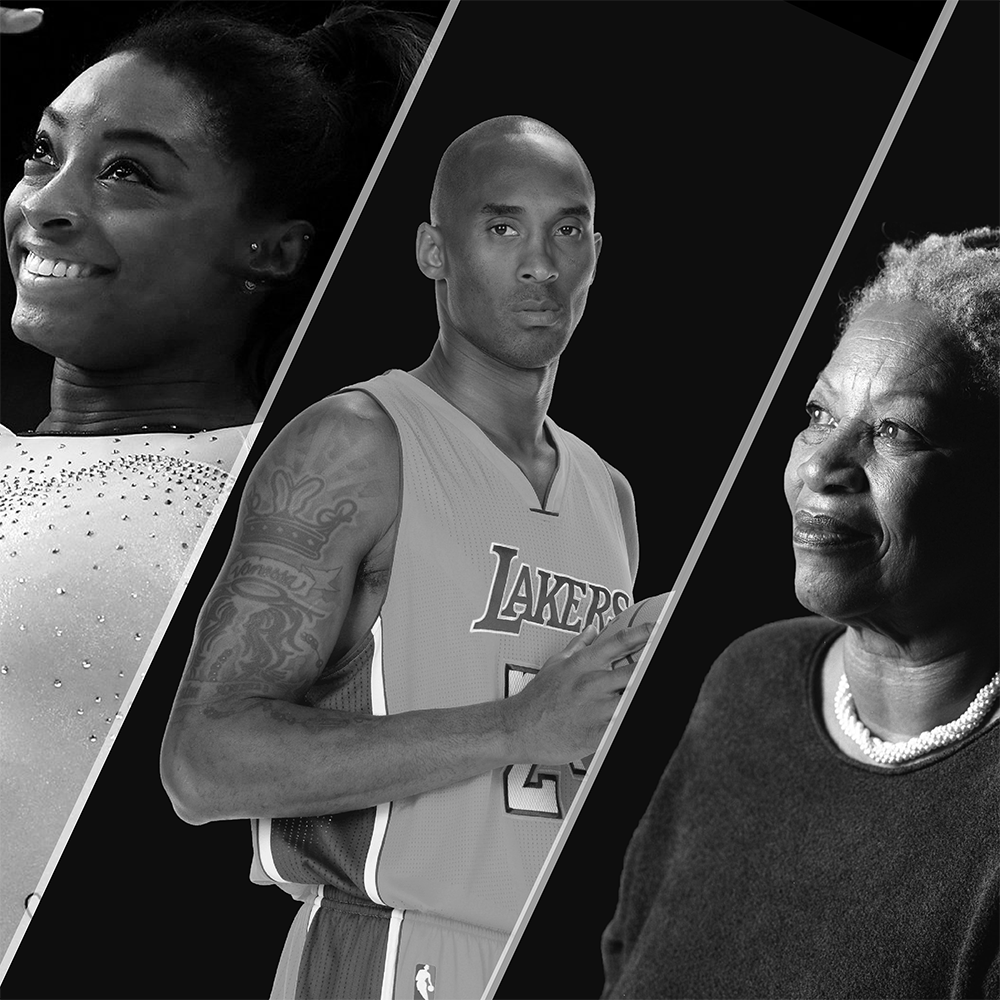

Within Black Catholicism you will also find Simone Biles, the most decorated American gymnast of all time, and Herm Edwards, the former Jets coach. You will find the legendary writers Claude McKay and Toni Morrison. And don’t forget the jazz great Mary Lou Williams. In it you will also find a litany of NBA players, including Kendrick Perkins, Kerry Kittles, Serge Ibaka, Pascal Siakam, Joel Embiid, and the aforementioned Laker legend we can all agree died too young.

Within Black Catholicism, you might also notice that we often bring front and center the most grand and heralded among our spiritual ancestors—namely, the handful of African-American individuals who are “on the way to sainthood.”

But without denigrating the great goal of sainthood, the one to which every faithful Catholic aspires, I must be honest: Black saints were never a huge deal to me. They played little to no part in my intellectual journey toward Catholicism. In my mind, once I was able to accept Catholicism for what it truly is—a diversely expressed, worldwide faith—they basically became, for me, a given. Of course there are Black Catholic saints. (And of course it will indeed be a significant day, especially for descendants of African slaves living stateside, when the pope canonizes the first American one.)

What was always more fascinating and attractive to me was the number of Black Catholics among the rolodex of celebrities in the mind of every millennial—whether it be from history class, ESPN, or the Wikipedia bunny trails on which we’ve all made a few hops. Because Catholic history is an integral part of Black history, their existence should come as no surprise. Yet because Black history is often forgotten history, they so often do.

If this article does nothing else for you, I hope it reminds—or informs—you that Catholicism is and always has been bigger than the parish down the street, the one you grew up in, the one(s) that hurt you, and all the ones whose names you can actually pronounce. We serve a God of the bigger picture, and all this month we celebrate Black history—one small and important picture within that beautiful and cruciform photomosaic.

According to my prior reasoning, Black Catholic celebrities should have been a given for me. Instead, they were and are for me a continual shock, perhaps because they hit much closer to home than a saint-to-be. I didn’t always aspire to be canonized, but I did always want to be like Kobe.

And despite his quiet faithfulness among his peers and within his professional craft, over the past few weeks millions of fans learned that Kobe Bryant was not only one of the greatest basketball players of all time, but also a faithful Black Catholic.

I want to be like Kobe more than ever.

Eternal rest grant to Kobe and Gianna Bryant, O Lord; and let light perpetual shine upon them. May their souls, and the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.