“Pivotal” is an important term at Word on Fire. To date, Bishop Barron has released ten films on the “Pivotal Players” of Catholicism, ranging from the fourth century with St. Augustine and St. Benedict to the twentieth century with Flannery O’Connor and Fulton Sheen. We may also recognize pivotal players whose lives are not tightly tethered to the Church, but whose generation-defining work redounds to our spiritual benefit. Few of us who face the culture with the Gospel would dispute that Bob Dylan is just such a figure.

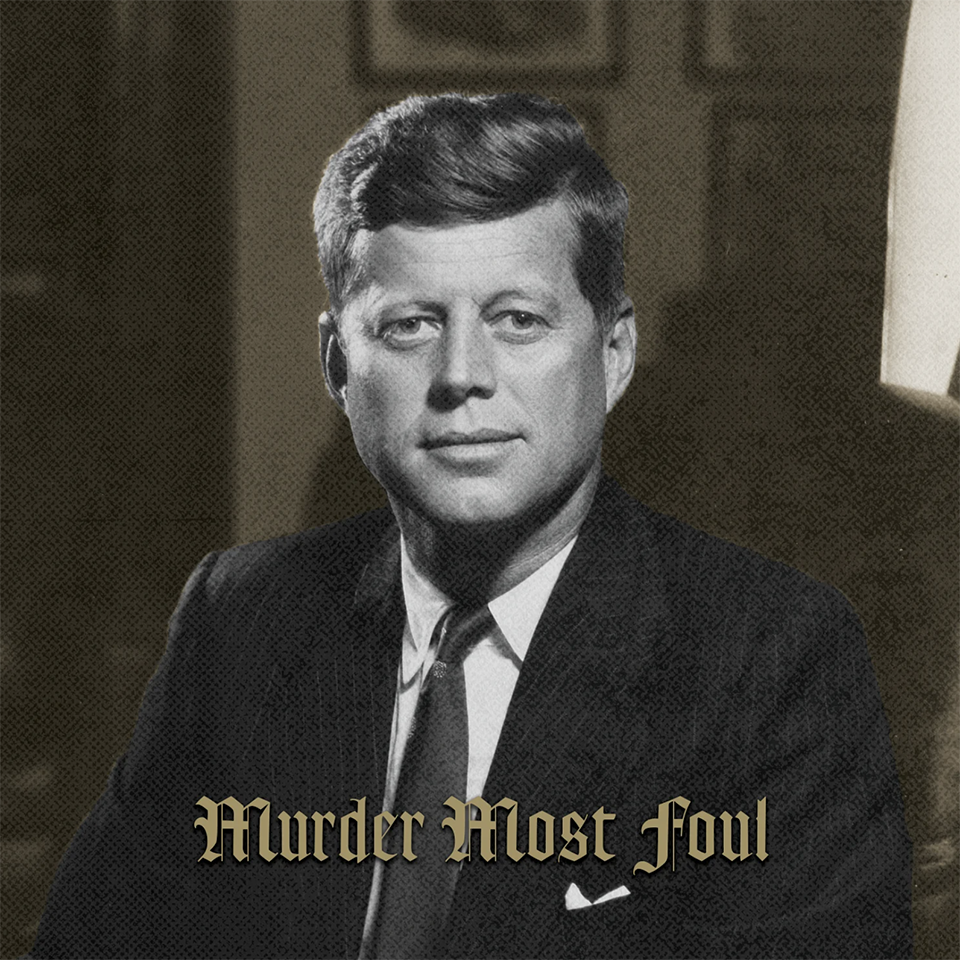

In his new seventeen-minute song, “Murder Most Foul”, this pivotal player is concerned with a particularly pivotal event: the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Fifty-seven years after the tragedy, Dylan asks us to take stock of history, and our own souls.

“Murder Most Foul” begins with the popular assumption that President Kennedy’s assassination was not accomplished according to official reports of the event. In the first two stanzas, “they” are the subject, speaking as a unified “we” to Kennedy himself, who pleads “wait a minute, boys,” before becoming the victim of the “greatest magic trick ever under the sun / Perfectly executed, skillfully done.” People with a penchant for, shall we say, alternative explanations for these pivotal events are already having a lot of fun decoding the song.

But for the culture-watching evangelist, it is the trajectory away from the assassination—the pivotal moment—that concerns us most. Here Dylan stands tall as the great sage and man of letters, the worthy recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature in 2016 (America’s first since Toni Morrison in 1993).

For such a prolific songwriter, “Murder Most Foul” is Dylan’s first original song to be released since 2012. It is a late edition to a great corpus of culture-watching art, and it joins an exalted list of some unusually long and mesmerizing songs in his catalog, such as “Desolation Row” and “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” And like “All Along the Watchtower” and “Every Grain of Sand,” it posits an inescapable spiritual dimension to reality. The powers of this world are never acting alone.

“Murder Most Foul” subtly offers us two explanations for our descent into decadence since 1963, before finally taking us through a long list of twentieth century artists whose works point beyond the feedback loop of political and social disarray born on “a dark day in Dallas.”

The first lens we look through is the quick death, after a quick rise, of the ideals that President Kennedy was assumed to embody. Dylan sets up a dichotomy:

I’m going to Woodstock, it’s the Aquarian Age

Then I’ll go to Altamont and sit near the stage.

Dylan is often considered one of the great prophets of this New Age. “The times, they are ‘a changin,’” yes. But in what direction? Dylan did not play Woodstock, but for many of his young fans, it became (and remains) a familiar reference point, symbolizing a new era of brotherhood that transcends the old divisions. But later in the same year was Altamont, another festival rock concert that Dylan did not play, and where violence and drug-induced debauchery made headlines. The latter exposed the fraud of the former. Likewise, when John F. Kennedy died, his brothers were called upon to take up his mantle, but one died (Robert) and the other was discredited by scandal (Edward). Dylan sings,

Don’t worry, Mr. President, help’s on the way

Your brothers are coming, there’ll be hell to pay

Brothers? What brothers? What’s this about hell?

Tell them, “We’re waiting. Keep coming,” we’ll get them as well.

Peace, love, and understanding was replaced with . . . well, nothing. Not even an abyss.

Dylan laments:

They mutilated his body, and they took out his brain

What more could they do? They piled on the pain

But his soul was not there where it was supposed to be at

For the last fifty years they’ve been searchin’ for that.

Dylan then gives us a second, larger lens to see where we are and where we’ve come from. The pivotal moment of President Kennedy’s death is not a vague end of the spirit of the age, but rather “the place where faith, hope, and charity died.” He develops Christ-like imagery for Kennedy, telling us, they “killed him like a human sacrifice.” The explanation, therefore, is not that people simply favor free love over real freedom, but that we are all susceptible to the darkest spiritual influences. He sings,

The day that they killed him, someone said to me, “Son

The age of the Antichrist has just only begun.”

He continues,

What’s new, pussycat? What’d I say?

I said the soul of a nation been torn away

And it’s beginning to go into a slow decay

And that it’s 36 hours past Judgment Day.

When we consider the vast upheavals in society and the Church that have occurred since the mid-1960s, Dylan’s diagnosis is a bitter but refreshing draft. How many universally recognized icons of our popular culture are willing even to consider the possibility that a disordered society is the result of disordered souls?

Where do we go from here?

Dylan no longer offers the same solution that he did during his overtly Christian period of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He does not come right out and say, as he sang in 1979, “It may be the devil or it may be the Lord / But you’re gonna have to serve somebody.” Instead, he tells us what he loves, and he invites us to “play” these same favorites: Etta James, John Lee Hooker, Oscar Peterson, and Stan Getz; but also “The Old Rugged Cross” and “In God We Trust.” Dylan finally adds his own composition to the list of essential spiritual memorabilia in the closing verse: “Play ‘Murder Most Foul.’”

As we contemplate the pivotal moment we are in now, one of the great pivotal players of recent memory spurs our contemplation. Maybe whatever was true, beautiful, and good that died in Dallas fifty-seven years ago lives on in “Murder Most Foul,” and in us who hear it.