Praying for Christopher Hitchens

By Rev. Robert Barron / From CNN.com

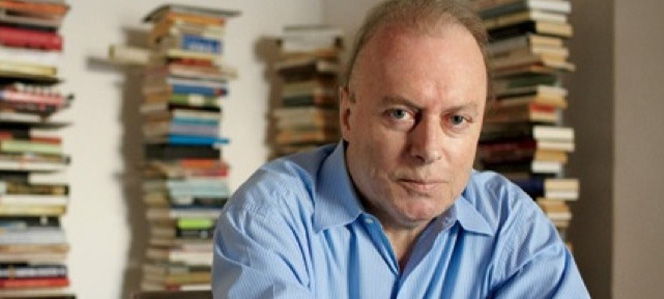

Perhaps you’ve heard of Christopher Hitchens. He is a British writer and cultural commentator who lives and works in Washington, D.C. For decades now, he has been observing the political/societal scene and writing about it in a particularly insightful, witty, and acerbic manner. Early in his career, he was something of a Trotskyite, but in the years following September 11th, he emerged as a strong advocate of the Iraq war and, much to the chagrin of his colleagues on the left, a supporter of George W. Bush. He is best known, certainly, for his recent contributions as a critic of religion. His book God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything appeared a couple of years ago and proved to be a bestseller. Since the publication of this text, Hitchens has travelled the country debating a series of religious thinkers—Christian, Muslim, and Jewish—meeting them with an extremely swift mind and wickedly barbed tongue. Along with Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, and Richard Dawkins, he is one of the “four horsemen” of the New Atheism, the movement that advocates an aggressive, take-no-prisoners approach to the claims of faith. I think it’s fair to say that Hitchens is playing today the role that another brilliant Englishman, Bertrand Russell, played nearly a century ago, namely, that of religion’s public enemy number one.

Perhaps you’ve heard of Christopher Hitchens. He is a British writer and cultural commentator who lives and works in Washington, D.C. For decades now, he has been observing the political/societal scene and writing about it in a particularly insightful, witty, and acerbic manner. Early in his career, he was something of a Trotskyite, but in the years following September 11th, he emerged as a strong advocate of the Iraq war and, much to the chagrin of his colleagues on the left, a supporter of George W. Bush. He is best known, certainly, for his recent contributions as a critic of religion. His book God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything appeared a couple of years ago and proved to be a bestseller. Since the publication of this text, Hitchens has travelled the country debating a series of religious thinkers—Christian, Muslim, and Jewish—meeting them with an extremely swift mind and wickedly barbed tongue. Along with Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, and Richard Dawkins, he is one of the “four horsemen” of the New Atheism, the movement that advocates an aggressive, take-no-prisoners approach to the claims of faith. I think it’s fair to say that Hitchens is playing today the role that another brilliant Englishman, Bertrand Russell, played nearly a century ago, namely, that of religion’s public enemy number one.

Just a few weeks ago, I picked up Hitchens’s latest, an autobiography entitled Hitch-22. The book is a lot like the man: by turns funny, strange, deeply wise, infuriating, outrageous, critical, sometimes just plain baffling—and never dull. Something that surprised and intrigued me was Hitchens’s affection for two of my own literary heroes, Bob Dylan and Evelyn Waugh. He echoes a number of top critics in saying that Dylan should be mentioned along with T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden as one of the poetic giants of the twentieth-century. (Now I’ve said something like that for years, but people usually just write me off as an overly enthusiastic Dylan fanatic). And for Waugh, the author of, among many other novels, A Handful of Dust and Helena, Hitchens has almost unlimited enthusiasm. And here’s why I say I was surprised: both Dylan and Waugh are inescapably religious writers. In fact, I would argue that it is impossible to understand and appreciate their work apart from the deeply Biblical sensibility that they share. In songs from all parts of his career—A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall, Blowin’ in the Wind, All Along the Watchtower, New Morning, Gotta Serve Somebody, Every Grain of Sand—Dylan draws on the Scriptures, and Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited is one of the greatest celebrations of Catholicism in all of modern literature. I confess I began to wonder whether, despite his brassy atheism, Mr. Hitchens didn’t have a good deal of sensitivity to things religious.

Well this very thought was on my mind when word came out last week that Hitchens was suffering from esophageal cancer, a particularly aggressive and unforgiving form of the disease. I realize that certain believers couldn’t resist the temptation to see in this misfortune the avenging hand of God: the one who for so long blasphemed God was now getting his just reward. But it’s always a very tricky business to interpret the purpose of the divine providence. After all, plenty of good, even saintly, people die prematurely from terrible diseases all the time, and lots of atheists and vile sinners live long prosperous lives before dying peacefully in their beds. Hitchens’s disease is indeed ingredient in God’s providence, since, at the very least, it was permitted by the one whose wisdom “stretches from end to end mightily.” But what it means and why it was allowed remain essentially opaque to us. Might it be an occasion for the famous atheist to reconsider his position? Perhaps. Might it be the means by which Hitchens comes to think more deeply about the ultimate meaning of things? Could be. Might it bring others to faith? Maybe. Might it have a significance that no one on the scene today could even in principle grasp? Probably.

But what struck me with particular power as I surveyed the Catholic media was that the vast, vast majority of Catholics reported Hitchens’s disease and then, with transparent sincerity, urged people to pray for him. In making that recommendation, of course, they were on very sure ground indeed. Jesus said, “love your enemies; bless those who curse you; pray for those who maltreat you. Christopher Hitchens is undoubtedly the enemy of Christianity—even of Christians—but he is also a child of God, loved into being and destined for eternal life. Therefore, followers of Jesus must pray for him and want what is best for him. Hitchens seeks by means of specious argument, insinuation, and sometimes plain smear-tactics to undermine religion. He ought to be opposed, vigorously, with counter-argument and clarification of fact. But all the while, he ought to be respected. One of the greatest Catholic apologists of all time, G.K. Chesterton, debated the agnostic George Bernard Shaw up and down England, and their arguments were often pointed and aggressive; but after the debates, the two friends could be seen drinking and laughing together. That’s a model of how a Christian treats his intellectual opponents.

So read Christopher Hitchens; disagree with him and get angry with him; defend the faith against his attacks. And pray for him.