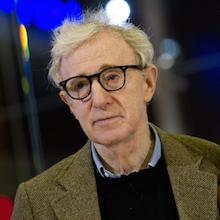

I was chagrined, but not entirely surprised, when I read Woody Allen’s recent ruminations on ultimate things. To state it bluntly, Woody could not be any bleaker in regard to the issue of meaning in the universe. We live, he said, in a godless and purposeless world. The earth came into existence through mere chance and one day it, along with every work of art and cultural accomplishment, will be incinerated. The universe as a whole will expand and cool until there is nothing left but the void. Every hundred years or so, he continued, a coterie of human beings will be “flushed away” and another will replace it until it is similarly eliminated. So why does he bother making films—roughly one every year? Well, he explained, in order to distract us from the awful truth about the meaninglessness of everything, we need diversions, and this is the service that artists provide. In some ways, low level entertainers are probably more socially useful than high-brow artistes, since the former manage to distract more people than the latter. After delivering himself of this sunny appraisal, he quipped, “I hope everyone has a nice afternoon!”

Woody Allen’s perspective represents a limit-case of what philosopher Charles Taylor calls “the buffered self,” which is to say, an identity totally cut off from any connection to the transcendent. On this reading, this world is all we’ve got, and any window to another more permanent mode of existence remains tightly shut. Prior to the modern period, Taylor observes, the contrary idea of the “porous self” was in the ascendency. This means a self that is, in various ways and under various circumstances, open to a dimension of existence that goes beyond ordinary experience. If you consult the philosophers of antiquity and the Middle Ages, you would find a very frank acknowledgement that what Woody Allen observed about the physical world is largely true. Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas all knew that material objects come and go, that human beings inevitably pass away, that all of our great works of art will eventually cease to exist. But those great thinkers wouldn’t have succumbed to Allen’s desperate nihilism. Why? Because they also believed that there were real links to a higher world available within ordinary experience, that certain clues within the world tip us off to the truth that there is more to reality than meets the eye.

One of these routes of access to the transcendent is beauty. In Plato’s Symposium, we can read an exquisite speech by a woman named Diotima. She describes the experience of seeing something truly beautiful—an object, a work of art, a lovely person, etc.—and she remarks that this experience carries with it a kind of aura, for it lifts the observer to a consideration of the Beautiful itself, the source of all particular beauty. If you want to see a more modern version of Diotima’s speech, take a look at the evocative section of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, wherein the narrator relates his encounter with a beautiful girl standing in the surf off the Dublin strand and concludes with the exclamation, “Oh heavenly God.” John Paul II was standing in this same tradition when, in his wonderful Letter to Artists, he spoke of the artist’s vocation as mediating God through beauty. To characterize artistic beauty as a mere distraction from the psychological oppression of nihilism is a tragic reductionism.

A second classical avenue to transcendence is morality, more precisely, the unconditioned demand of the good. On purely nihilist grounds, it is exceptionally difficult to say why anyone should be morally upright. If there are starving children in Africa, if there are people dying of AIDS in this country, if Christians are being systematically persecuted around the world…well who cares? Every hundred years or so, a coterie of human beings is flushed away and the cold universe looks on with utter indifference. So why not just eat, drink, and be merry and dull our sensitivities to innocent suffering and injustice as best we can? In point of fact, the press of moral obligation itself links us to the transcendent, for it places us in the presence of a properly eternal value. The violation of one person cries out, quite literally, to heaven for vengeance; and the performance of one truly noble moral act is a participation in the Good itself, the source of all particular goodness. Indeed, even some of those who claim to be atheists and nihilists implicitly acknowledge this truth by the very passion of their moral commitments, a very clear case in point being Christopher Hitchens. One can find a disturbing verification of Woody Allen’s rejection of this principle in two of his better films, “Crimes and Misdemeanors” from the 1980’s and “Match Point” from the 2000’s. In both movies, men commit horrendous crimes, but after a relatively brief period of regret, they move on with their pampered lives. No judgment comes, and all returns to normal. So it goes in a flattened out world in which the moral link to transcendence has been severed.

Perhaps this conviction is born of my affection for many of Woody Allen’s films, but I’m convinced that the great auteur doesn’t finally believe his own philosophy. There are simply too many hints of beauty, truth, and goodness in his movies, and despite all his protests, these speak of a reality that transcends this fleeting world.