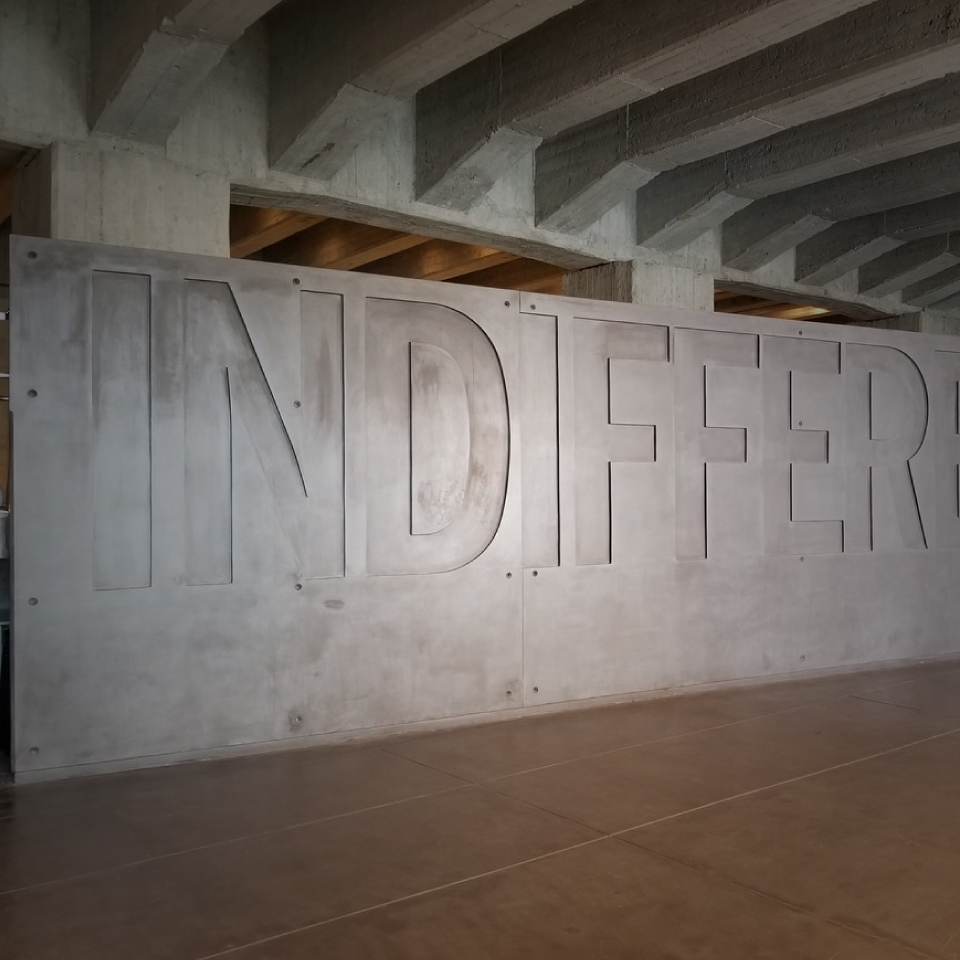

In lifeless bold letters across a slab of concrete, the word “Indifferenza” (“Indifference”) is etched at Milan’s Holocaust Memorial. The somber word, heavy with plaintive meaning and tragic history, serves as both a constant and cautionary reminder of the grave horrors that can befall humanity if we give into such a state of apathy. The museum stands where Platform 21 used to, a train station that seventy years ago was secretly used to load Jews onto trains headed for death camps. The museum opened in 2013, and in taking seriously the writing on the wall, recently has sheltered and accommodated foreign refugees: an influx of men, women, and children who have fled war, hunger, and persecution in northern Africa.

Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize winning novelist, political activist, and Holocaust survivor, knew well the consequences of a world lulled by the nefarious pitch of indifference: “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference.”

Wiesel’s words conjure a sobering passage from the Book of Revelation in their indictment of those who stand detached, disengaged and disinterested with the world and the suffering of those in it: “I know your works; I know that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish you were either cold or hot. So, because you are lukewarm, neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth” (Rev. 3:15-16).

Moreover in the Gospels, Christ harbors convicting words for those who ignore the least brothers of his. In one parable, the Rich Man ends up in hell not because of a sinful action on his part, but rather a selfish inaction—his “blindness” to the needs of Lazarus. Pope Francis has also warned of a “globalization of indifference,” a great temptation by which Christians of the West can often be lured:

Our heart grows cold. As long as I am relatively healthy and comfortable, I don’t think about those less well off. Today, this selfish attitude of indifference has taken on global proportions, to the extent that we can speak of a globalization of indifference. It is a problem which we, as Christians, need to confront.

Interestingly, although comfort and health can muddy our sight of those suffering in our midst, we at the same time have access to more human misery and pain than ever before. We do not have to exert much energy to view a good measure of misfortune. Daily through television, online news sources, social media, etc., we are exposed to gruesome, mind-searing images and stories. We see with eyes that would often rather remain blind to the plight of those living in our world, and not necessarily because we don’t care, but because the misery is far too great and we far too helpless. With a battering of our senses with such a widened scope of human suffering and pain, we can often only process it through avoidance—and if not avoidance, then disengaged curiosity.

A CNN article from a few years back, “Is the Internet Killing Empathy” by Gary Small and Gigi Vorgan, raises serious questions about the seeming loss of empathy—and, consequently, the rise of indifference—experienced by many in our society: “Have our brains become so desensitized by a 24/7, all-you-can-eat diet of lurid flickering images that we’ve lost all perspective on appropriateness and compassion when another human being apparently suffers a medical emergency? Have we become a society of detached voyeurs?”

By “medical emergency,” Small and Gigi are referring to an incident involving a Los Angeles news reporter who seemingly had a stroke on live TV (it turned out only to be a migraine). The video became a viral sensation, incurring a shocking slew of likes and shares. The article continues, speculating why such alarming behavior is becoming more widespread:

[8 to 18 year-old’s] brains have become “wired” to use their tech gadgets effectively in order to multi-task—staying connected with friends, texting and searching online endlessly, often exposing their brains to shocking and sensational images and videos. Many people are desensitizing their neural circuits to the horrors they see, while not getting much, if any, off-line training in empathic skills.

Our culture’s media is aware of the mass appeal of sensational stories, often feeding this morbid appetite with accounts of lurid suffering and disturbing violence. The gritty, neo-noir film Nightcrawler, starring Jake Gyllenhall, unearths this very infatuation embedded within our culture. The film explores the harrowing underbelly of crime journalism. Gyllenhall’s sociopathic character, Louis Bloom, and others in the film, are motivated to record and broadcast the most violent and crime-riddled narratives they can dig up in the urban sprawl of Los Angeles, not for the sake of responsibly informing society—the noble and necessary purpose of journalism—but rather, to package them neatly with a bow as forms of voyeuristic entertainment.

As we become privy to the suffering of others to such a massive extent, how do we respond with hearts made of flesh the way Christ would have us? I don’t think there is an easy answer. If we’re honest, we are helpless against the majority of suffering and evil we witness. There is the need for humility in looking out at a world that is deeply wounded and accepting that we can’t save it by our own efforts. Only God can—and did—shoulder the totality of the world’s sin and suffering. In most cases, all we can do is pray, fast, and mourn with others. God can use our sacrifices and prayers to dispense his grace in mysterious ways. Who knows how skipping a meal for the sake of someone enduring persecution in the Middle East can restore justice? Or how proffering a heartfelt Our Father can restore healing? Prayer and sacrifice, when united to Christ’s suffering on the cross, allows us to do more than we can possibly imagine—surely more than we’ll ever know in this life.

However, we are still responsible to bring about God’s loving mercy into the world through our own acts—through our very flesh that images Christ’s body. As his baptized children, we are his sacraments—signs of his grace in a world gone awry. God calls us to act, for we are people of reason and will, tasked with the great command to work for the salvation of the whole world. “If a brother or sister has nothing to wear and has no food for the day, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace, keep warm, and eat well,’ but you do not give them the necessities of the body, what good is it?” (James 2:15-16)

We are called to pray for some, and act for others. We are called to let God show us when he wants us simply to stand in solidarity with our neighbor who is suffering and offer him or her God’s mercy through prayer and sacrifice, and when we can be the hands and feet of Christ in a literal way. If we are honest in our prayers and listen for the voice of God, he will let us know when we are to explicitly and concretely enter into others’ suffering and strive to relieve it. And when he doesn’t right away, we do the best we can to hold the tension of the world—to love when there is only darkness. We know some are called to defend the unborn, others to feed the hungry, others to bring hope to the imprisoned, others to teach the doubtful, and so on.

I’ve heard some say that witnessing the plight and misery of others allows for us to be thankful of our own situation. While I agree that there can be a grace in seeing more clearly the blessings we have compared with another who lacks those same blessings—and a proper response is always gratitude to God for his undeserved gifts—I think we have to be careful. Surely, the misery of others does not serve only to help us appreciate how blessed we are and then rest comfortably behind the curtain of those very gifts and blessings. We can never stop at a gratitude that is content with only a thank you. Instead, in our sheer gratefulness, we should desire to pour out those blessings we have onto others. Our prayer should be a thank you, followed by a question: How are you asking me to bless others—especially those suffering—with the blessings you’ve given me, Lord? Because for every blessing we have, we also have our own inimitable sufferings for which we need others to share God’s mercy with us.

The Christian response is not avoidance or numbness in the midst of our suffering neighbors, no matter how great or small. Instead, let us seek to hold the tension of living in a fallen but redeemed world, eschewing an indifference that has no place in the hearts of God’s people.

The most deadly poison of our times is indifference. And this happens, although the praise of God should know no limits. Let us strive, therefore, to praise Him to the greatest extent of our powers. (St. Maximilian Kolbe)